In the aftermath of the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan, an array of humanitarian and development agencies arrived to the historically secluded region of Pakistan-administered Kashmir (PaK). For most it was the first time they interacted with this region. Due to a series of physical and logistical factors the initial relief was slow to arrive and despite an effort to make post-earthquake assistance universal, most assistance was targeted. As in other humanitarian crises, institutional issues within development agencies made them adopt a pragmatic decision to target assistance.

From a citizen’s perspective, people saw the earthquake not as a singular event but as two:

1. The experience of the earthquake itself

2. The experience of post-earthquake assistance and relief

In my conversations in bazaars around the region in the years that followed, people’s stories about the suffering they experienced were characterised by this dual feature of the earthquake.

While the earthquake itself had a negative impact throughout the region – cutting across class, caste, and sectarian groups – the post-earthquake assistance had a more ambiguous impact, benefitting those with better physical and social access to aid, while excluding others.

During relief and reconstruction stages, location and transport infrastructure, along with people’s ability to create and/or use existing social networks, were vital factors in determining who received assistance. For example, households living near urban centres, tarred roads or helicopter landing zones, received faster and more assistance than households living further away. Social networks based on caste, kinship, and clientelistic ties also helped to accelerate and increase this assistance.

As I highlighted in my earlier blog, Lessons from Pakistan’s 2005 earthquake for Nepal’s reconstruction, most agencies tried to use a community-focused approach to relief, reconstruction, and rehabilitation.

However, with no clear understanding of what constitutes a community, and in a hurry to obtain quick results, their decision-making was often captured or biased towards dominant or elite groups, who claimed to be the voice of the ‘community.’ As a result, many development agencies exacerbated the exclusion and marginalisation of certain groups by overlooking networks of patronage embedded in local social hierarchies.

The importance of understanding biradari as a key influencing factor governing social organisation

Similar to most of Pakistan and northern India, the key factor governing social organisation in the earthquake-afflicted region is the biradari, a caste-like or at times a kinship corporate entity.

It is through biradari-ism – clientelistic biradari networks – that most people attempt to gain access to power and resources, for example in the organisation of voting blocs during elections, in getting access to jobs in state and non-state organisations, and in claiming a stake in social protection mechanisms.

So perhaps unsurprisingly biradaris were crucial for people’s access to earthquake assistance.

For instance, the assessment of a cash transfer programme targeting vulnerable families (PDF) during the transition from relief and reconstruction discovered 50% leakage and 50% under-coverage, meaning one in two families that received the cash was not eligible and one in two of the deserving families was excluded. The biggest problem was one of enumeration, and although the researchers don’t investigate enumerator bias, they infer that enumerators entered the wrong information to benefit kinship groups.

Our research revealed poor choice of target groups by reconstruction agencies

A year after the earthquake, my LUMS students and I undertook a research project to examine how reconstruction agencies decided upon their target groups/areas. We approached 30 development agencies of the 91 officially selected by the Pakistani government to operate in the area post-earthquake, interviewing both programme managers and fieldworkers.

Half of these agencies chose “the village” as their target unit, one third chose “the settlement” which is a sub-unit of the village, while the remaining number either zoomed in and targeted individual households directly, or zoomed out and targeted union councils.

Two problems with identifying “the village” as the target community in this mountainous region

First, there is an issue of representation.

Each village is, on average, composed of five settlements, with the main settlement giving its name to the village. So when an agency stated it was working with a particular village, the assumption was that it was reaching the whole village, whereas in reality it was largely working with the main settlement after-which the village was named and failing to reach the remaining settlements.

The second problem is that by targeting villages, and equating villages to communities, agencies would often overlook the influence of dominant biradaris in those villages and allow for capture.

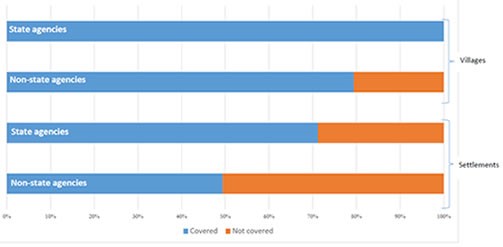

We also collected data from the field, asking villagers (male and female) from 59 settlements belonging to 12 villages in five union councils in Bagh (PaK) and Balakot (Khyber Pakhtunkwa) districts who had assisted them. Although this was not a representative sample, it was still indicative. Worryingly, we found that when we analysed the village data in detail state and non-state agencies did not reach 30% and 50% of the settlements, respectively.

From late 2008 until early 2010, I was a constant visitor to three of these villages in Bagh district, while conducting fieldwork for my doctoral studies. It was during this time that I noticed another important difference between the experience of the earthquake and the experience of post-earthquake assistance: while the former had a nonhuman origin, the latter had human roots.

When people talked about ”living in inhuman conditions”, these conditions were not always caused by the earthquake itself, but by the relief efforts that followed; and in these cases the inhumanity was not aleatory, but perpetrated by a human ‘someone’ – often an outsider (i.e. outside PaK).

With the onset of the earthquake some villagers suddenly became dependent on charity, a life they equated with beggars. Worse still, as relief and reconstruction efforts were not universal but targeted – and at times mis-targeted – they felt forced to beg for assistance which was not automatically allocated to them.

As a newspaper seller in a rural bazaar told me, “people thought that they would all get aid, but since the influentials got aid and they didn’t, that made them feel deprived like never before.”

Agencies new to the region mis-target more

Now I would be grossly generalising if I said all agencies behaved the same way. Of course, there were differences between them.

The biggest difference had to do with precedence: agencies that were working in the earthquake-affected areas before the earthquake were more aware of local social hierarchies, regardless of whether they were local, national, international, state or non-state agencies.

Of the 30 agencies I mentioned earlier, the vast majority that chose “the village” as their target community were the agencies that had never worked in the region before. And despite settlements not appearing in census documents in which the lowest measurable unit is the village, every local government official and most of the agencies working in the region before the earthquake had a list of all the settlements in every village.

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) presently uses a “Who does What Where” form to coordinate its relief operations. Maybe it’s time for agencies to have a “Just-in-Case” form, designed for unexpected disasters: if something happens, who are we going to help, and how?