I attended an event by UN Women Indonesia called “16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence” in Jakarta after I left my wonderful academic year at IDS. It was series of seminars and workshops by feminist organisations to celebrate International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women and Human Rights Day. The event helped me to reconnect with feminist activism in Indonesia after being out the country for a year.

Image: Participants gave their signatures as a sign to support the “#MulaiBicara” or “start to speak up!” campaign to eliminate violence against women. I wrote “maju terus!” which means “keep on going!”

This writing is to share my reflections on the event. Also to share knowledge I gained through my studies at IDS, of some different approaches that Indonesian activists and academia can utilise to strengthen the amazing works they’ve done so far.

Power as positive force for social change

It can been seen from the event that Indonesian people’s understanding of “power” is still limited as power-over. Activists and academia translate “power” into “kuasa”, which means “control” in English (hence “relasi kuasa” as “power relations”). I’m glad the event provided space to spread the understanding about power to the public, especially when Dr. Lidwina Inge Nurtjahyo brought discussion about power relations within law during the seminar on “Evaluating Law Enforcement on Rape in Indonesia”. However, with such a narrative, I’m afraid non-academic and non-activist people will perceive power as power-over only. Such a discourse can perpetuate the belief that there’s no way to get what we want other than controlling others.

I believe the academia and activists have roles in engaging the public to exercise positive expressions of power: “power-with” and power-within/empowerment. Power-over is negative because it is about a zero-sum game, one will gain power only when others lose their power. While “power-with” is about cooperation across different interests, and “power-within” is about finding inner strengths to exercise agency and transform our own life. Social transformation that we want can only be achieved if everybody exercises positive power. It also requires people to perform self-reflexivity to be aware of what kind of hidden and invisible power they exercise in every action.

Engaging people to exercise positive power can only be done if we expand understanding about power for social change.

Intersectionality

The term “intersectionality” was not mentioned throughout the event. Perhaps because this term came from a different context. Intersectionality is multiple forms of adversities reinforcing one another that an individual experience because of their identities: gender, race, class, ethnicity, class, physical (dis)ability, etc. This concept occurred to highlight the different kinds of oppression Black women experience compared to White women as the legacy of slavery system. Such a racial issue happens differently in Indonesia.

I felt the urgency of intersectionality for Indonesia activism when I attended the talkshow on “Recognising Sexual Violence, Listen and Support the Victims”. One of the speakers was Melanie Subono, a half-White local celebrity whose father is a successful business man. It was obvious that she didn’t understand the verbal harassment (catcall) cases, let alone the variety of other sexual violence cases. I felt she benefited from priveleges that protect her from experiencing harassment. She proposed only one solution “to speak up,” which I believe is risky in perpetuating victim-blaming (as if the problem is on us, woman who doesn’t speak up).

Intersectionality lens is needed to understand the heterogeneity of women in Indonesia. We need to discuss racism issues (i.e. systemic discrimination towards Chinese Indonesian or demeaning jokes against dark-skinned and curly-hair people) although these are different from what happens in the Western countries. We must also acknowledge the diversity of class, religion, ethnicity, education level, and physical (dis)ability, etc. that are also linked with conflict over resources. Intersectionality can help us to understand different life experiences of each individual and avoid oversimplification of the problem.

Social justice, instead of human rights

Feminist activism still uses “human rights” as their fundamental framework. One example is Solidaritas Perempuan, a local NGO which held a discussion about their activism to repeal the discriminatory Sharia Law Qonun Jinayat in Aceh Province. While I’m a big supporter of human rights, I’m afraid arguing for human rights isn’t enough in the Indonesian context. “Human rights” was born in the West, where people are more individualistic. Meanwhile, Indonesian society still emphasises the importance of family and community cohesion, as well as religion (if not predominantly). If we want social change, we must engage with the society. When we say to them ‘women’s rights is human rights,’ they will ask us back ‘what’s the benefit for us? What’s in it for my community?’. Certainly, a different approach is needed.

My suggestion is to frame feminism work as “social justice”. The idea of social justice is more familiar to Indonesian society because it is our national foundation. Pancasila no. 5. Social justice means peace and happiness for all, so we can show the benefit of our work for family and society at large. This includes men and the conservative people.

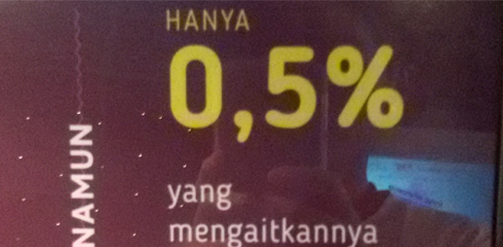

On the last day of the event, MaPPI FHUI, a law think-tank based at the University of Indonesia, exhibited infographic posters about sexual violence cases in Indonesia. One of which explained the impact of sexual violence for the victims. If we use social justice as our main argument, we can also highlight the impact of sexual violence to male perpetrators, family and community. Therefore, ‘social justice’ is a better framing to help other people support our gender work.

Image: Research from MaPPI FHUI showed 0.5% of sexual violence perpetrators say that they committed the crime because of the victim’s sexy dress.

Care economy

“Care” was missing from the 16 Days of Activism event. There was one talk-show about economic empowerment by Plan International presenting two young female farmers from Eastern Indonesia. I felt inspired by their spirit. But in all talks during the event, the drudgery of unpaid care work that women must bear and sometimes worsened by economic empowerment initiatives were not discussed. I am yet to find any local or international NGO that works on unpaid care work issues in Indonesia.

Since feminist activists and academia always champion integration of the public and private spheres, it’s time to address care in our empowerment work. It requires us to be critical about whether we challenge or entrench the neoliberal system that harms women. Activists should be the pioneers of highlighting the importance of care to economy and ask for equal distribution of care work between men and women as well as among family, community and state. Academia should help to make unpaid care work visible for policy recommendation.

I felt grateful that the “16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence” reminded me that I’m not alone in hoping and working for gender equality in Indonesia. But we still have work to do together. My message is, sometimes we have to accept that our approach isn’t working when we get stuck, and we need to explore different ways of looking at things. I will be learning how to apply my knowledge gained at IDS, and I see this writing as a start of my contribution towards feminist movement in Indonesia.