Over the last five to ten years, the number of people owning smartphones has grown rapidly, especially in lower-and-middle-income countries. Now synonymous with cameras, these smartphones are responsible for the majority of images taken worldwide.

Embedded cameras are ever more present in our work, study and everyday life, and as we grapple to find the ‘new normal’ post Covid-19 pandemic this only looks set to continue. Inspired by their increasing omnipresence in everyday life, we conducted a short research study in 2021 to better understand the sustainability, and ultimately, developmental impacts of this change.

A mixed picture

Embedded cameras are democratising access to photography. This was demonstrated in a striking National Geographic picture of nomadic Kyrgyz herders in a remote part of Afghanistan with no cellular signal, who owned mobile phones for the sole purpose of taking photos. Though smartphone ownership is still much more common among the young, the wealthy and the well-educated in lower-and-middle-income countries, billions of people who until recently had no means of documenting and digitally sharing what matters to them, can now do so.

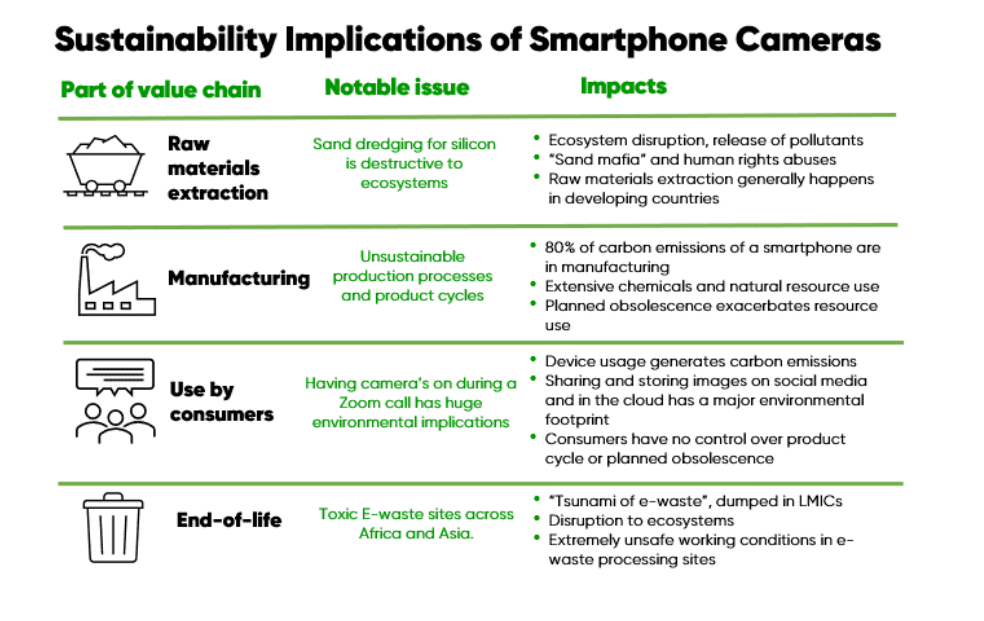

Yet the enormous growth in the consumption of cameras and the wider electronics they are embedded in raises questions of the costs to the environment, particularly in lower-and-middle-income countries. To get the full picture, we evaluated the global value chain, from raw material extraction through to how consumers buy, make use of, and dispose of, their devices.

Raw materials

Devices with embedded cameras contain raw materials including silicon and plastic, as well as rare earth minerals like gold and lithium, which often originate in politically fragile countries. As Maxim Grew, founder of The Intrepid Camera Company, explained to us, behind each glass lens is a silicon chip (CMOS sensor) created from silty sand, dredged mainly from rivers in developing countries. “Sand dredging for glass and silicon chips could be one of the next big environmental disasters. And we’re also running out of [this type of] sand, and you can’t make it. Species have gone extinct because of getting sand” then used in phones.”

Intensifying competition for minerals has also emboldened and empowered “sand mafias”. These gangs are known to use child slave labour, to sell sand on the black market, and have been responsible for killing journalists and activists.

Manufacturing

Mass over-production compounds the environmental and human cost of devices. In ‘planned obsolescence’ practices, companies downgrade products in attempts to force consumers to buy new devices. As Maxim Grew explained: “the camera is the relentless driving force for buying new tech. [Companies] on their adverts always talk about the camera, they compare who’s got more megapixels. They never say ‘it’s easier to text’.”

Since the camera is one of the most common components of a phone to break, it often drives the replacement of otherwise fixable phones. Manufacturers entice consumers to buy new devices with camera upgrades. Photography journalist Tom Ang told us “When cameras start to drive product development, promotion and new product cycles, then … you can start saying ‘actually, this is not a phone that takes pictures, but it’s a camera you can call on’.”

Use by consumers

The way that camera use is now integrated into our daily lives also produces potentially unsustainable effects. Social media pressures are resulting in an ever-growing number of photos and videos taken and posted online. Of the 1.4 trillion photos taken in 2020, more than 90 percent were on cameras embedded in phones.

Many of these photos are stored on servers or the ‘cloud’, which uses much more electricity than local storage. The operation of servers generates huge carbon emissions, resulting from the transmission and remote storage of data. Currently, only 12% of data centres storing photos are energy efficient and over 7 billion trees would have to be planted to offset their carbon emissions. Though variable depending on national infrastructure, calculations from the ‘Selfie Index’ show it takes an average of one tree to offset the carbon emissions of just ten photos taken and shared online.

Covid-19 has also increased our use of videoconferencing software. Research shows that having the camera on during a Zoom call significantly increases an individual’s carbon footprint, generating between 150 and 1000 grams of CO2 per hour (8,887 grams are emitted by burning a gallon of gasoline). An hour of videoconferencing uses 2 to 12 litres of water and and requires a land area the size of an iPad mini, all of which could be reduced by 96% if the camera was not used.

End-of-life

The WHO has highlighted how a “tsunami of e-waste” is jeopardising the health of millions, particularly through hazardous recycling processes. In 2018, 50 million metric tonnes of e-waste were produced, of which only 20% was recycled.

Embedded cameras in devices with short lifespans exacerbate this problem. E-waste, mainly originating in higher income countries, is sent to Africa and Asia, often under false pretences that it will be reused or recycled. At Agbogbloshie in Ghana, roughly 40,000 mainly migrant workers live and work in informal e-waste processing, posing threats to their health and wellbeing.

Addressing the sustainability challenges

Our research showed that embedded cameras can be a force of both sustainable and unsustainable development. Following Amartya Sen’s Development as Freedom philosophy, the fact that more people can now take and share photos of what matters to them is a profoundly positive change. Yet, they are also driving potentially destructive patterns of production and consumption. The conflict begs an important question: what will it take to address these sustainability issues?

Transcript for the image table above:

Sustainability implications of smartphone cameras

|

Part of value chain |

Notable issue |

Impacts |

|

Raw materials extraction |

Sand dredging for silicon is destructive to ecosystems |

|

|

Manufacturing |

Unsustainable Manufacturing production processes and |

|

|

Use by consumers |

Having cameras on during a Zoom call has huge |

|

|

End-of-life |

Toxic E-waste sites across Africa and Asia. |

|

Governments can act as both regulators and orchestrators of change. They have begun to do so, for instance, by passing ‘right to repair’ legislations. This stipulates that manufacturers must make spare parts available to consumers and third-party companies, but it doesn’t yet cover smartphones and laptops. Due to the global operations of manufacturers such as Samsung and Apple, international coordination is desperately required.

There is hope that manufacturers’ self-interest in managing e-waste and “closing loops” grows as essential resources become scarcer. Further planned obsolescence is gaining increasing backlash, and major smartphone manufacturers have faced, and lost, lawsuits over it. Yet profit motives alone will not suffice. It often pays to pollute, and firms can offload many costs of unsustainable production onto the public.

Consumers can also exercise purchasing power, but only with sufficient transparency and education. Whilst new consumption models, such as the Dutch manufacturers Fairphone, are growing, price constraints mean these are only accessible for a minority of conscious high-end consumers.

To harness the development benefits of embedded cameras, users in low- and middle-income countries need access to affordable, sustainable products. For this, it is crucial that Governments and intergovernmental bodies incentivise and regulate the industry. Camera phones are capable of greatly enriching lives, but this must not come at the cost of environmental and social impoverishment.