The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) describes persistent fragility as occurring in areas or regions that are “in protracted crisis” (pdf) and characterised by recurrent natural disasters, conflict, persistent food crisis, a breakdown of livelihoods and/or insufficient institutional capacity to respond to the various crises.

Today, 1.2 billion people live in countries affected by these conditions. In the 22 countries identified by FAO as being in protracted crisis (or containing areas in protracted crisis), more than 166 million people are undernourished, representing nearly 40 per cent of the population of those countries and nearly 20 per cent of all undernourished people in the world. What is more, in these places, fundamental human needs go unsatisfied: women are unsafe, children are malnourished and not in school, youth lack opportunities to build their livelihoods, and communities are divided and insecure.

What is the role of agriculture in fragile contexts?

Understanding the role of the state in using agriculture to improve nutrition in such contexts involves a balance between what the state: 1) ought to do; 2) what it can do and; 3) what it is willing to do. However, it is a fallacy to think that the effective administration or ‘management’ of development is a technical matter alone.

Introducing ‘political will’ into the equation adds layers of complex, and at times counter-intuitive, dynamics. The reality of political decision making involves policy makers balancing day-to-day bargains with long term objectives, their own individual ambitions with wider regional or national strategies, and indeed, actioning evidence based policies depending on their political saleability. Political will is also based on whether a jurisdiction has the ability and resources to create the change they want to see, whether it is improved nutrition or access to healthcare.

Finally, political will involves a complex mix of preferences. This means that it also varies across places and people because of different contexts. These can include different types of institutions and prevailing local norms, which do not necessarily match dominant thinking on ‘good governance’.

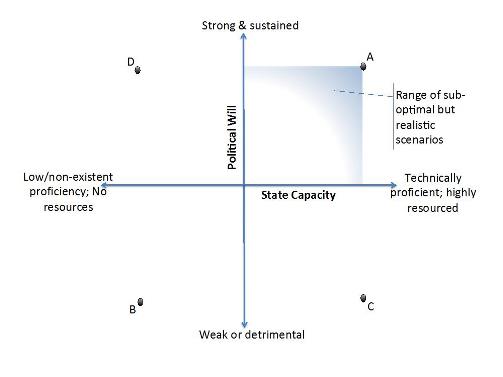

Four ‘hypothetical’ scenarios of political will and capacity in affecting change

- Scenario A: strong and sustained political will to pursue an objective in conjunction with a state that is technically proficient and resourced to deliver that objective.

- Scenario B: non-existent political will and weak capacity. Or, this scenario could be strong will and capacity to pursue an end that is detrimental to development (for example, a strong will and capacity to persecute a particular population through war or other policies).

- Scenario C: strong political will to pursue a development objective, but a weak capacity to deliver it.

- Scenario D: strong state capacity to deliver, but without the political will to back it.

If Scenario A is an unrealistic ideal, it is possible to conceive other, yet more realistic, situations wherein the combination of some degree of political will (that is restricted to a sub-national body or only through particular political mandates, for instance) and some degree of state capacity (that is without cutting edge technical proficiency or piecemeal resources). With this in mind, if we are interested in finding out how agriculture and agri-food systems can be better designed to advance nutrition in fragile contexts, it is also worth asking:

If Scenario A is an unrealistic ideal, it is possible to conceive other, yet more realistic, situations wherein the combination of some degree of political will (that is restricted to a sub-national body or only through particular political mandates, for instance) and some degree of state capacity (that is without cutting edge technical proficiency or piecemeal resources). With this in mind, if we are interested in finding out how agriculture and agri-food systems can be better designed to advance nutrition in fragile contexts, it is also worth asking:

- How does the political will and organisational capacity of government influence agriculture-nutritional linkages?

- How can evidence-based recommendations for agriculture-nutrition policy, programmes and interventions take account of political will and organisational capacity of government?

- What are the implications of weak political will and organisational capacity of government for the uptake of evidence on agriculture-nutrition linkages?

The answers to these questions are not straightforward. They will inevitably fall in a grey area and are not necessarily optimal, but they represent realistic combinations of political will and the state’s organisational capacity. And for this reason, affecting change in fragile contexts will always be more art, than science.

—

- Visit the Leveraging Agriculture for Nutrition in South Asia (LANSA) to find out more about their work on fragile contexts, including Afghanistan and nutrition sensitive agriculture.

- Download Jaideep Gupte’s working paper on Leveraging agriculture for nutrition in fragile contexts.