Mobile technology and data will play a huge role in how agriculture and health information is delivered, administered and monitored in the future. Mobile phones, in particular, are already widely used to deliver health and agricultural messaging with a view to changing people’s behaviours and practices. However, as with all new tech solutions, rigorous evaluation is needed to assess its true impact, reach and influence on those it is supposed to benefit.

A consortium of researchers from IDS, Gamos and the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) are evaluating the mNutrition programme in Tanzania and Ghana to assess its’ impact, cost effectiveness and commercial viability. mNutrition is a mobile phone-based information service aiming to improve knowledge, behaviour and practices related to nutrition. We are evaluating an mHealth plus mNutrition intervention in Tanzania and a mAgri plus mNutrition intervention in Ghana. We use a mixed-methods approach to provide in-depth insights and rigorously assess the impact of the mobile phone-based service to inform future programming.

Credit: Infographics produced by Fruit Design, copyright IDS

Information gaps

Despite good progress in health in Tanzania, undernutrition remains a public health challenge and childhood stunting levels and micronutrient deficiencies remain high. Women in the target districts have some nutrition knowledge gaps and they also struggle to access credible information to address these gaps. Mothers and pregnant women said that mobile phone-based information could offer an inexpensive and convenient channel for new information. They also liked the fact that SMS messages could be read repeatedly, were private and had the potential to be very timely in terms of specific information needs at different stages of a child’s growth, such as weaning.

Child undernutrition is also a persistent challenge in Ghana and the country has one of the lowest agricultural yields per hectare in the world. The programme in Ghana aims to promote behaviour change around key farming decisions and practices, and around maternal and other household practices that are likely to result in improved nutritional health within a household.

Barriers to using the services

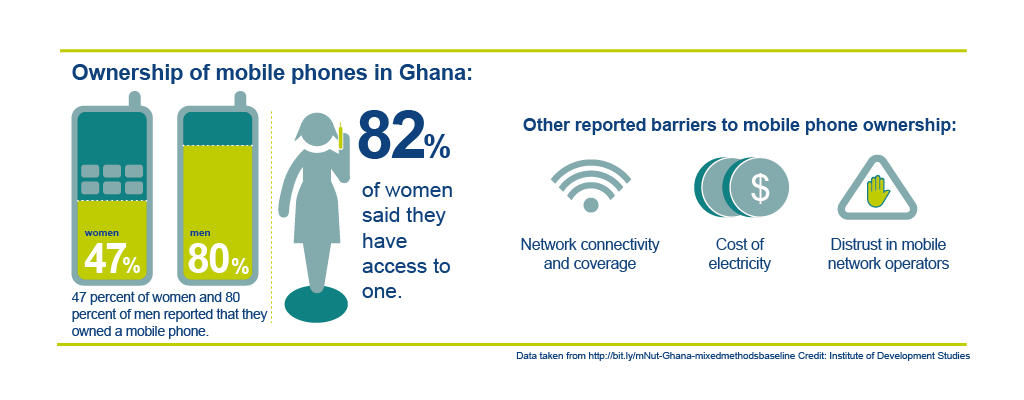

However, we found a range of barriers related to broader gendered social inequalities and economic realities which mobile information programmes cannot address. Whilst mobile ownership was widespread in Tanzania, fewer women own mobile phones and access was often strictly controlled and monitored by the owner (usually their spouse). Most households did not have access to electricity and had to charge mobiles at a kiosk (for a charge). In households where both men and women owned a mobile phone, charging the man’s phone was a priority. A major challenge was that users have multiple sim cards so there was a high likelihood that they would miss messages sent to the number they signed up with.

In Ghana, we found that Vodafone Farmers Club (VFC) might be a good way to improve access to credible information on agricultural practices, especially for female farmers. However, the programme is reliant on farmers having access to the Vodafone network which had poor coverage in the target regions.

Profit vs impact

Farmers had some strong doubts about the trustworthiness of mobile network operators (MNOs). There was a widespread perception that MNOs were mainly interested in generating profits and not in helping ‘poor farmers’ and this may well be a barrier to the success of the service.

VFC in Ghana uses recorded voice messages as a way to reach farmers with limited literacy, but farmers’ unfamiliarity with this method of information delivery might be a problem inhibiting widespread uptake of this service. In both countries, structural issues beyond the reach of the programme may also prove problematic. High levels of illiteracy make SMS a challenging platform; only 17 per cent of the women and 31 per cent of household heads (mainly men) could read a phrase in English.

These findings are explored in more detail in the executive summaries (Ghana and Tanzania) and reports (Ghana and Tanzania). They demonstrate the value of in-depth qualitative studies on digital development programmes such as mNutrition; through these studies, we can understand the ways that mobile phones can influence behaviour change in health and nutrition and inform more effective programme design. But we must also understand the limits of mobile phone technology in the face of issues such as illiteracy and gendered inequalities in access to technology.