In 2000, the first Pakistani government body to monitor women’s human rights was set up. But, two decades on, its future is in peril because no agreement can be reached on who to appoint as Chair.

When the first Pakistani government body to monitor the state’s compliance with women’s human rights was set up in 2000, the feminist movement in Pakistan celebrated an important victory. But, after two decades of the National Commission on the Status of Women (NCSW), its future is in peril because parliamentarians cannot agree on who to appoint as its new chair. The post has been empty since the term of its last chair, the seasoned feminist activist Khawar Mumtaz, expired in November 2019. It is a cautionary tale about how institutional gains for women’s rights can be swept away when political interests and feminist backlash coincide.

I recently published a research study into what NCSW had achieved over the last twenty years to further gender justice and support the goals of feminist activists in Pakistan. It found NCSW had helped build coalitions for women’s rights by bringing together dedicated bureaucrats, concerned politicians, and strategic government bodies to work for reforms and reduce the risks of collective action for civil society activists. Countering the reprisals that feminists often face from right-wing and religious organizations for their critique of discriminatory laws promulgated by the government’s Islamization policy during the 1980s, NCSW raised activists’ concerns and used rights-based framing in the corridors of power to reduce their vulnerability and consolidate support for policy reforms.

Reforming the zina laws

The first example of a successful NCSW initiative was in helping build parliamentary support for the 2006 reform in Pakistan’s controversial zina laws. These laws, based on Quranic teachings, were promulgated by General Zia ul-Haq’s military regime (1977-1988). They ban all sex outside of marriage and make it punishable by death. Victims of rape were liable to zina charges if they could not prove their assault. Yet, in response to the growing numbers of women incarcerated and sentencing under zina laws of some women to death, the contemporary women’s movement mobilised against the regime.

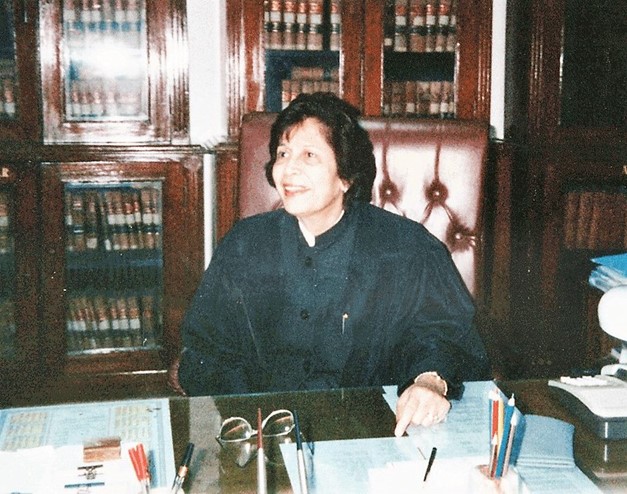

Once civilian rule returned during the 1990s, politicians were reluctant to address the zina laws for fear of antagonizing religious parties, or upsetting a public that had grown increasingly rigid in its interpretation of Islamic laws. When Justice Majida Rizvi took over as chair of NCSW in 2002 she brought vast experience with in zina court proceedings, and was determined to build political backing for change. She set up a committee of experts including feminist activists and lawyers who concluded that the zina laws needed to be repealed altogether.

Justice Majida Rizvi faced death threats and public protest for her views, but also support from the women’s movement and civil society organizations. A public debate on repealing zina laws took place with religious scholars and feminists locked in furious argument. The Council of Islamic Ideology, an influential government body that drafted the original laws, issued a detailed review with recommendations for amendments to deprive them of their abusive potential. President Musharraf, a military ruler keen to appear more moderate than General Zia, supported an open debate.

Finally, a political opportunity came ahead of a visit to the United States. Musharraf allowed a reform bill to be tabled in Parliament. The new act brought the crime of rape back into the penal code and made it procedurally more difficult to register zina cases. This success result in the numbers of women accused and imprisoned for illicit sex falling rapidly.

Banning tribal jirgas

The second NCSW initiative I analysed was its court petition to ban jirgas, or tribal councils. In Pakistan, dysfunctional governance institutions and criminal justice system perpetuate the role of jirgas in dispute resolution, enabling them to order harmful cultural practices such as honour killings or the exchange of girls to settle feuds. Feminists and human rights activists successfully lobbied for new laws to ban some egregious practices against women, but the influence and impunity of jirgas remained.

Activists from the Women’s Action Forum (WAF), the feminist lobby group that spear-headed opposition to General Zia’s policies, began a systematic campaign in the province of Sindh during 2008, sending 60,000 signatures to NCSW calling for an end to jirgas. This campaign was strengthened in 2009 when Anis Haroon became the new chair of NCSW. She was a well-known WAF activist and had worked for decades with a national women’s rights advocacy NGO called Aurat Foundation. Haroon hosted a national conference against religious militancy and extremism, and set up a committee of legal experts to develop NCSW’s gender justice agenda.

This led in 2012 to NCSW filing a constitutional petition against jirgas. WAF, advocacy NGOs, and individual politicians investigated a series of jirga decisions and raised awareness against these tribal councils through protests and publishing research. The Supreme Court of Pakistan delayed in hearing their petition, partly because many influential male politicians sit on jirga councils themselves, but finally, in January 2019, it declared jirgas unconstitutional, recognising their role in illegal practices violating women’s fundamental rights.

Understanding the success of the NCSW

My research found that when its initiatives have worked, the NCSW was led by experienced feminist activists who used their convening power to mobilise support from feminist groups and politicians to achieve policy reforms. When Khawar Mumtaz became Chair after Anis Haroon, she too brought a history of WAF activism and leadership at Shirkat Gah (another national feminist advocacy NGO) to the role. NCSW could deliver on its mandate when it had support of the ruling party to monitor women’s rights, and enjoyed good working relationships with women parliamentarians, donor agencies, media, and other government bodies.

Challenge to sustained success

Political support was fundamental to NCSW’s effectiveness but the body faces considerable constraints that continue to undermine its ability to build coalitions for further progress on gender rights and to mitigate the risks for activists and women on the ground when they organise for change. As backlash against the feminist Aurat March from extremist groups accelerated this year, activists needed a strong NCSW with political backing to advance their claims. Yet without a Chair, and with the parliamentary selection committee unable to agree on a new appointment, it fell upon the Islamabad High Court to order the government to make the NCSW operative again.

As Mumtaz observes, a dysfunctional NCSW “has lost its continuity and momentum”. “Tracking progress on the implementation of laws, advice on policies and legislation, response mechanisms to gender-based violence, documentation, coordination with provinces and provincial commissions — are all at a standstill.” The delay in appointing the new Chair of the NCSW reflects the government’s lack of priority towards women’s issues, and abandonment of the feminists who are left to advocate alone.

Ayesha Khan is author of The Women’s Movement in Pakistan: Activism, Islam and Democracy (2018, I.B.Tauris). She works at the Collective for Social Science Research in Karachi. Her study Pakistan’s National Commission on the Status of Women: A Sandwich Strategy Initiative was supported by the Accountability Research Center at American University, USA.