A strong focus on achieving impact as we tackle intractable challenges and aim to foster transformative change is a positive force for the development sector as a whole. It has opened up the discussion about what we mean by development outcomes and impact and how to use evidence to become more effective in achieving change. Yet, on the other hand, a focus on impact tends to also emphasise the size of change, how we measure it and how much value for money is created by any intervention. Current discussions around achieving impact at scale – the holy grail for any development project – tend to assume that once we know that interventions work, we can then roll them out – or take them to scale – to achieve greater change for less cost.

But some challenges we are engaging with – such as tackling violence against women and girls, improving opportunities for people with disabilities, or reducing the worst forms of child labour –require that we focus on the highly complex and context-specific nature of the required social, political and economic change, where wrong approaches also risk a backlash and end up doing more harm than good. This reality is far more complex than the simple scaling up narrative assumes. If we are to take seriously our attempts to reach the hardest to reach, then we need a much better understanding about how scale can be achieved.

What does it take to achieve impact at scale for these fundamental challenges for the progressive ‘leave no one behind’ agenda of the Global Goals?

In response to this question, the K4D (Knowledge, Evidence and Learning for Development) programme facilitated a Learning Journey for the UK Department for International Development (DFID), to build understanding of how to design scaling strategies for inclusive approaches to complex social change. A rapid evidence review provided a summary of scaling up theories of change, identifying four main types of scale-up that are often interconnected:

- Vertical scale-up: political, policy and legal influencing and engaging activities within programmes; state (or other) institutionalisation of an intervention.

- Functional scale-up: adding new components to existing programmes and services.

- Organisational scale-up: growing the role and capacity of an original organisation and/or creating new partnerships.

- Evidence and learning scale-up: investing in local, national and international learning and research.

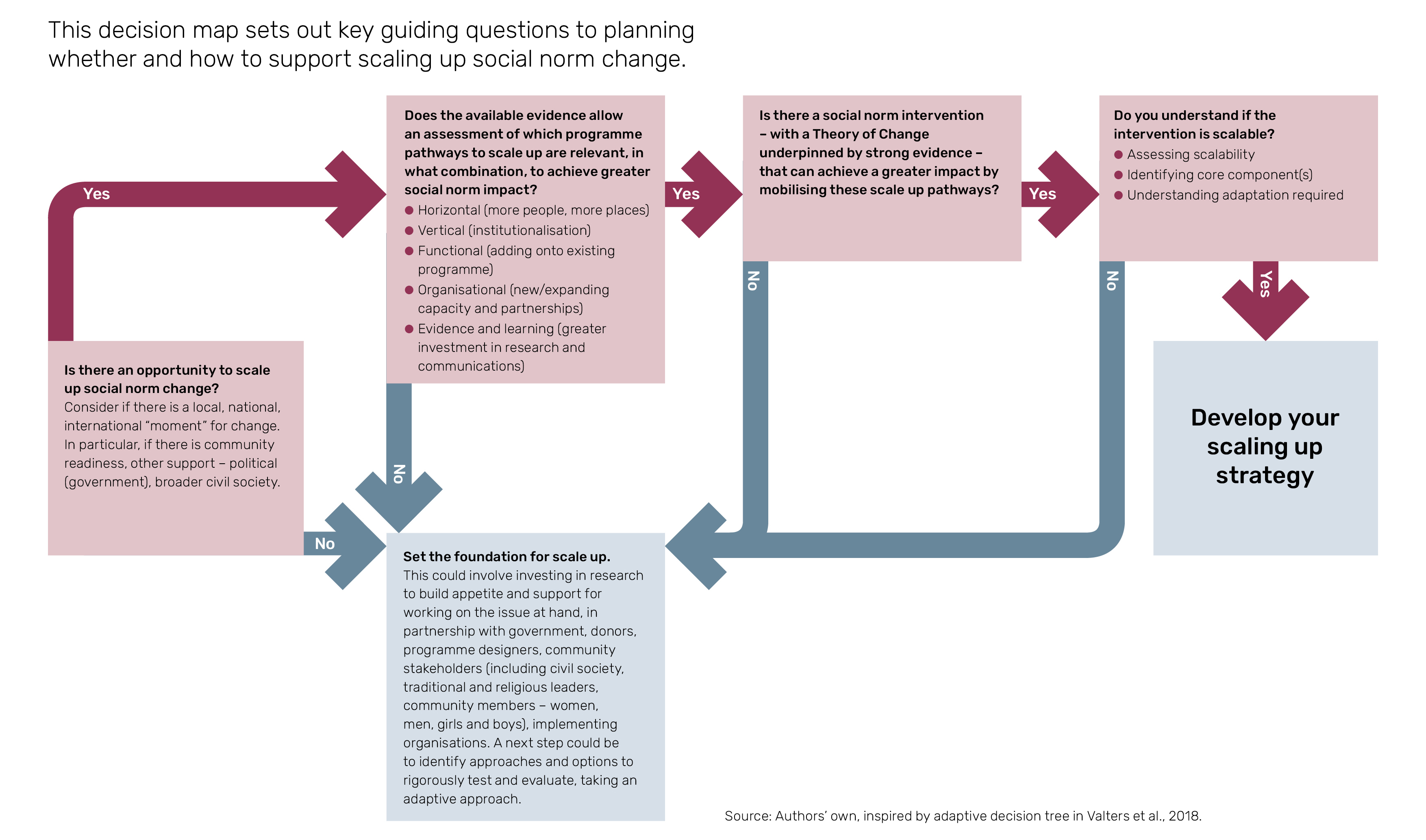

While this summary was useful, it didn’t go far enough to help programmers make decisions about which pathway is relevant for their programme, and indeed how they might bake scaling into programme design from the outset. What, for example, should a DFID Business Case say about how scaling will be achieved – which pathway to choose and why – and what resources are required to make it a reality?

Fueling discussion and learning

The findings from the review fuelled further discussion with a wide range of experts (including Susan Igras and Rebecka Lundgren of the Institute for Reproductive Health, Georgetown University; Lori Michau of Raising Voices; and Michelle Remme of the United Nations University International Institute for Global Health) and a concerted effort to identify cases to learn from. The findings of the Learning Journey were used to produce a Guidance Note on Scaling up Social Norm Change which includes 22 practical lessons from a number of programmes. The purpose of the guidance note is to help DFID advisers to:

- Assess the opportunities for scale-up in a given context/moment.

- Develop a vision of successful scaled-up impact on harmful behaviours underpinned by social norms, and a related scaling theory of change.

- Plan new interventions supporting social norm shifts and plan how to take existing ones to scale.

It is not a comprehensive ‘how to’ guide but rather sets out a series of guiding questions that programme designers can work through to plan if and how scaling up is possible and desirable. It is explicitly shared as a draft, with an invitation to DFID advisers to trial it and share their learning and improve the guidance further. In this new field, where evidence is weak, our experiences are what we must fall back on to help us push boundaries.

Source: © DFID – Crown copyright 2019

Source: © DFID – Crown copyright 2019

Here at IDS, we are putting the guide to use already as we work to detail in three countries the interventions of the DFID funded Child Labour Action Research in South and Southeast Asia (CLARISSA) programme. CLARISSA aims to generate evidence and learn from interventions aimed at tackling the drivers of the worst forms of child labour in Nepal, Bangladesh and Myanmar. Many of the interventions will be innovations that are generated by children themselves. If and how to scale these interventions in the complicated and uncertain context of child labour is currently a key consideration of the programme.

The guidance, together with its accompanying set of four Briefs, are proving a fabulous resource as we grapple with rethinking scaling in complex and innovative programming.