In this third blog in our series ‘Lessons on using Contribution Analysis for impact evaluation’ we give an example of how a contribution analysis inspired approach was used in a short four-month consultancy project.

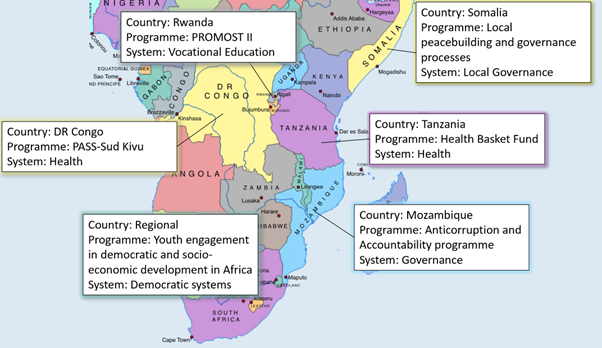

We supported the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) in a learning journey on how their programmes are contributing to systemic change in authoritarian contexts in Eastern and Southern Africa (ESA). A learning journey aims to help SDC learn from the experiences of their programme offices in order to make recommendations for ongoing and future work.

One regional and five country-level programmes were included in the learning journey. The contribution analysis (CA) was conducted on portfolio level with each programme as a case. In this blog we describe how the idea of causal hotspots was especially useful in this short project to zoom in, unpack and make the hard choices of where to focus our learning efforts.

Transcript of the information in the image above (figure 1):

Country: Rwanda

Programme: PROMOST II

System: Vocational education

Country: Somalia

Programme: Local peacebuilding and governance processes

System: Local governance

Country: DR Congo

Programme: PASS-Sud Kivu

System: Health

Country: Tanzania

Programme: Health Basket Fund

System: Health

Country: Regional

Programme: Youth engagement in democratic and socio-economic development in Africa

System: Democratic systems

Country: Mozambique

Programme: Anti Corruption and Accountability programme

System: Governance

Contribution analysis for learning: an 8-step journey

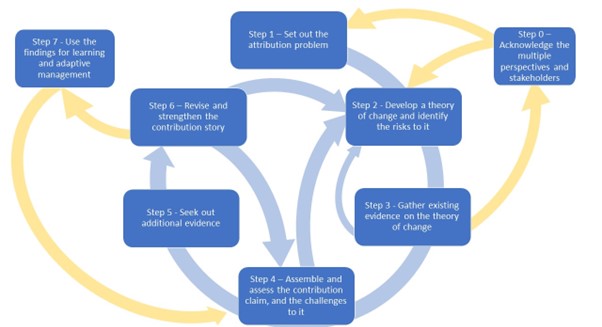

We used the 8-step CA approach described by Giel Ton, which adds two steps to the normal 6 steps of CA: Step 7 where the evidence-supported contribution claims are used to review, learn, and make programme improvements and Step 0, which acknowledges multiple perspectives of stakeholders.

Figure 2: Eight step contribution analysis diagram.

Step 0 – Acknowledging multiple perspectives and stakeholders. The learning journey started with identifying the boundaries, stakeholders, perspectives and relationships of the system that each of the SDC programmes aimed to influence. This follows insights about evaluation of system change as shared in the Special issue on System- and Complexity-informed Evaluation in New Directions in Evaluation and Ramalingam and colleagues”. We specifically used the boundary and stakeholder analysis tools from the Inclusive Systemic Evaluation for Gender Equality, Environments, and Marginalized Voices (ISE4GEMS) evaluation approach. Analyses were completed using programme documents provided by SDC staff and information gathered through workshops and interviews. Ideally, an evaluation includes these stakeholders’ input in shaping the evaluation, due to the short timeframe of this consultancy, not all stakeholders could be engaged.

Step 1 and 2 – Set out attribution problem and develop theory of change. We ran a workshop with staff from each programme in which we expanded on the stakeholder analysis and discussed any systems changes they have observed. During the workshops we also interrogated their existing ToCs to surface critical underlying assumptions and risks to it and identified causal hotspots within their ToCs by asking the workshop participants 1) Where do you think the evidence for this change is most likely contested? 2) What is the most exciting part of this ToC for you? (See Blog 1 in this series).

The second question especially proved to be useful and engaging. Causal hotspots that were identified in multiple case studies were policy dialogues (where multiple stakeholders and national governments come together to discuss what changes need implementing) and decentralisation (the process of moving power away from centralised government towards local governments).

Step 3 – Gather existing evidence on the ToC was done using programme documentation (e.g. annual reports, previous evaluations) and information provided by programme staff in the workshops on what changes they are observing. This was used to identify available evidence that could support or refute the critical assumptions and the contribution claim.

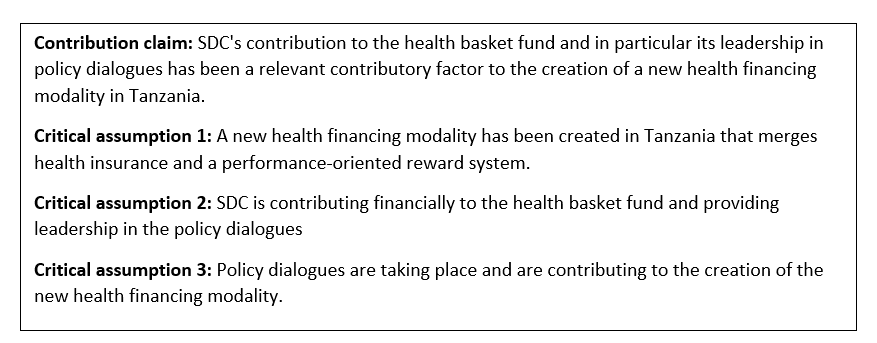

Step 4 – Assemble and assess contribution claim. Based on the documentation and workshops, we developed contribution claims of whether and how each programme is a contributory factor to a larger, more complex, change process in the system. Each contribution claim consisted of one key claim statement and three to five critical assumptions underpinning the contribution claim that roughly aligned with the activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts in the ToC. The critical assumptions help to break down the overall contribution claim into assumptions that need to be true for the contribution claim to be true. The contribution claims and assumptions were shared with the programme staff for them to check whether these aligned with their perspectives.

A weakness at this stage was that all information was provided by SDC staff directly involved in the programme. We had already planned to interview external stakeholders and the gaps that were identified in the available evidence helped us to develop interview questions for these interviews. For example, in relation to the policy dialogue hotspot, we asked questions about SDC’s role in policy dialogues, how essential this role is, and what outcomes have resulted from policy dialogues.

Step 5 – Seek out additional evidence. This was done through 2-3 key informant interviews per programme and Google and media searches. We reviewed academic literature for evidence on how policy dialogues and decentralisation contribute to systemic changes in authoritarian contexts and the role of development cooperation agencies in this.

Step 6 – Revise and strengthen the contribution story. We synthesized the evidence from Step 5, which was used to elaborate the contribution claims from Step 4. Contributions stories presented the evidence on how the specific SDC programme is (or is not) a contributory factor to observed system changes. The contribution stories were shared and checked with programme staff and key informants, whose feedback was used to refine the contribution stories.

Step 7 – Use the findings for learning. The contribution stories were synthesised to identify strategies and challenges in contributing to system change in authoritarian contexts. This synthesis centred around policy dialogue and decentralisation as causal hotspots. The results were presented in a workshop with all staff that participated in this learning journey. The findings from the CA were used by staff to discuss ‘entry points’ for their work to influence systemic change.

Three benefits of using causal hotspots in a short consultancy

- Identifying causal hotspots within this short learning journey with six case studies helped to narrow down the focus and prevent getting lost in the complexity of systemic change.

- For portfolio level CAs with multiple cases, identifying causal hotspots for each case study helped to identify similarities across the cases. Learning on these causal hotspots could allow SDC ESA to create a portfolio-level ToC of how they are contributing to systemic change in authoritarian contexts.

- Explicitly asking the learning journey participants what excites them most about their ToC made them noticeably more engaged because they could specifically focus on the areas that they were most interested in. This buy-in is important for Step 7 to ensure learning from the evaluation is taken up. Ideally, future CAs should strive to engage a more diverse group of stakeholders (Step 0) and include them in identifying causal hotspots, to further strengthen the engagement and uptake of learning from evaluations across multiple stakeholders.