The increasing digitisation of the global economy is rapidly transforming industries and societies across the globe, presenting both opportunities and threats. Covid-19 has shined a spotlight on digital development. The stakes are high for African countries where technology, if introduced fairly, could be a game changer. But get it wrong and there are risks of digital inequalities self-perpetuating and self-amplifying exacerbating the marginalisation of the already less connected. African countries face a daunting digital governance challenge where privacy and security is under threat. This is especially the case for lower-income countries that lack the necessary capacities to compete and face the danger of being left behind. Appropriate policy interventions are therefore critical for inclusive digital development. Of primary importance is the issue of data governance; who owns data; who can process the data to derive digital intelligence; who can use digital intelligence to adapt business models and capture ‘data rents’; as well as questions of where should data be processed and stored.

The expansion of lobbying by digital players globally

Lobbying- described as the transfer of information between interest groups and policymakers, with the aim to influence facts, arguments, signals, or some combination thereof- has historically shaped trade policy, mainly through campaign contributions in developed economies such as the U.S., and through a narrower range of lobbying activities in developing countries. Unsurprisingly, trade policy with high returns has historically witnessed aggressive business lobbying, especially in the U.S. than elsewhere.

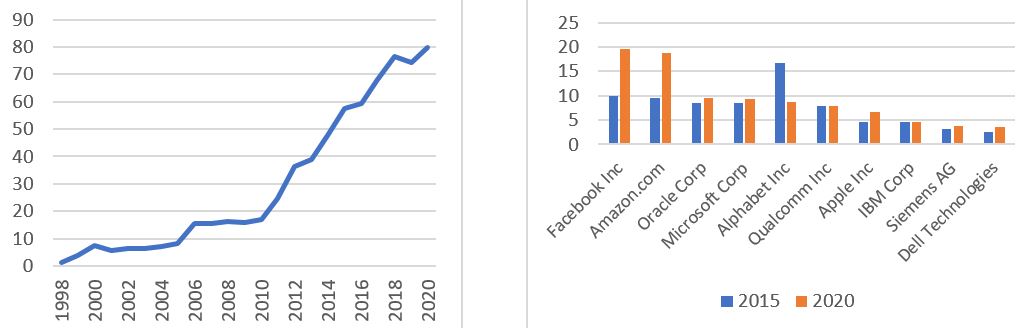

It then comes as no surprise that lobbyists are now pulling out all the stops in targeting digital trade. Figure 1 shows that lobbying by information and communications technology (ICT) firms in the U.S. shot up to almost $80 million by 2020; with lobbying expenditure by Facebook and Amazon doubling in the past five years (Figure 2). The combined market capitalisation of five Big Tech firms- Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft and Facebook- reached $7.5 trillion by 2020, which is three times the nominal gross domestic product (GDP) of all African nations combined, which sits at $2.5 trillion. They respectively have poured $63 million in the U.S, and another $22 million in the EU, to lobby on such issues.

Figure 1: ICT lobbying in the U.S. Figure 2: Lobbying spending by technology firms

Source: Author, constructed from data in the Centre for Responsive Politics. Data is in Million USD.

Source: Author, constructed from data in the Centre for Responsive Politics. Data is in Million USD.

The issues tech firms are lobbying for have also expanded beyond domestic ones to digital trade provisions in trade agreements, seeking free cross-border data flows, and bans on data localisation and source-code sharing as well as on any imposition of custom duties on digital products. However, with no consensus at the WTO, the digital trade agenda has pushed forward largely through bilateral and regional trade agreements. Outside the remit of the WTO, 86 countries released a consolidated negotiating text under the Joint Statement Initiative in 2020, for binding e-commerce rules, but predominantly shaped by developed economies, with only five African countries involved. At the same time, from India and South Africa’s communication at the WTO, as well as Africa Group’s position, there is an evident push-back against pre-mature global rule-making on digital trade issues, arguing the need for building national digital capabilities first, and concerns over tariff revenue losses estimated at $2.6 billion annually for Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries.

It is no surprise that in the Kenyan Free Trade Agreement negotiations, which commenced in July 2020, the U.S. is seeking to “establish state-of-the-art rules to ensure that “Kenya does not impose measures that restrict cross-border data flows and does not require local computing facilities”. To support the efforts of the Government of Kenya, a Kenya Private Sector Consortium has been formulated by the Kenya Private Sector Alliance (KEPSA). Alarmingly, this includes American private sector delegates such as those from Google and IBM. Further, if free cross-border flow of data is agreed, it will be in direct violation of the Kenya Data Protection Act, that allows personal data transfer only under certain circumstances. The dangers of unregulated personal data transfer has already been observed in the case of the Cambridge Analytica scandal in the last Kenyan general elections, as well as the 2015 general elections in Nigeria.

A continental digital trade protocol

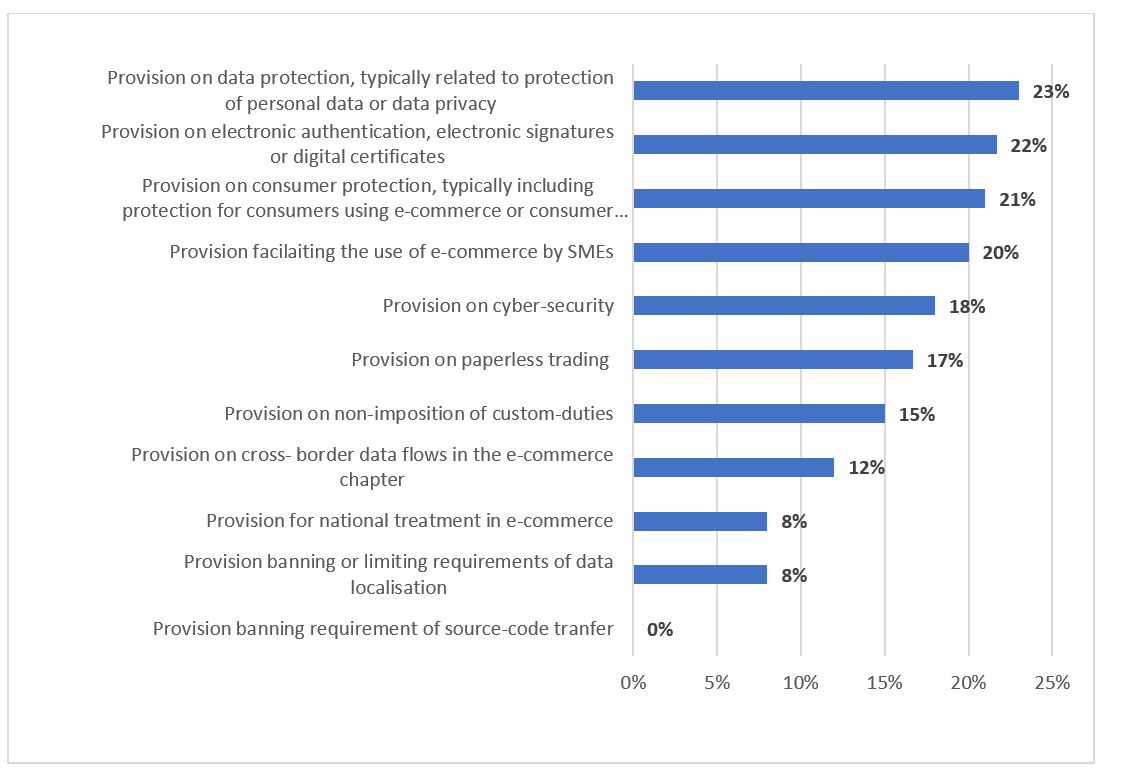

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) is set to include a digital trade/e-commerce protocol, presenting a unique opportunity for African countries to collectively establish common positions on e-commerce and related issues on data governance. Interestingly, while some North-South agreements have started to include provisions on data localisation, such provisions are uncommon for South-South trade, with only eight percent having a provision banning data localisation requirements. South-South trade agreements also tend to have weaker dispute resolution with sovereignty-based concerns of Southern countries.

Yet, provisions on data privacy, electronic trade facilitation and consumer protection are more common in South-South agreements (Figure 3). It means that African countries are entering continental negotiations with uneven levels and highly fragmented frameworks on e-commerce. A regional approach may therefore be more realistic and effective, especially with African private sector’s strong interest in intra-regional data sharing. To harmonise enforcement mechanisms, the AfCFTA can facilitate data protection authorities (DPAs) at the Regional Economic Community (REC) level, enabling countries to collectively address challenges faced by national DPAs in Africa.

Figure 3: Digital trade provisions in South-South trade agreements (% of agreements)

Source: Banga et al., (2021), constructed from the TAPED dataset. The official UN classification is followed for categorisation of South-South trade agreements.

Cross-border digital trade is also critically shaped by intellectual property (IP), competition and taxation issues. First, although backed by experienced internet giants from the Global North, many online marketplaces in Africa are plagued by the lack of IP infringement reporting mechanisms; and unclear application of ICT regulations makes enforcement difficult. Second, the dominance of Google and Facebook in digital advertising in South Africa underscores the need for updating competition policies. Africa’s own M-Pesa has scaled within a highly-particularistic and patronage-based political context, which shielded M-Pesa’s parent company Safaricom, and enabled M-Pesa to successfully block new entrants. Finally, on taxation, African countries have the immediate advantage of collecting taxes from digitalised transactions but there is often lack of certainty in how taxes apply, in the absence of which African tax administrators are sometimes pressured by the government to be ‘lenient’ with well-connected multinational enterprises.

Adopting a more politically informed approach towards digital development

Overcoming these issues and the influence of globally lobbyists requires African policymakers and development actors to actively insert political economy analysis in their thinking and design. This would enable them to understand embedded power structures in digital development and implications for inclusive development. On shaping incentives for digital trade, African governments can benefit from further analysis of existing digital trade provisions in South-South trade agreements, learning through South-South digital cooperation.

The AfCFTA can play a critical role in providing a guiding framework for African RECs to develop and harmonise regional data governance, intellectual property, tax, and competition frameworks, aligning with national and regional industrialisation priorities. Sector-specific data policies could be developed within the AfCFTA if countries want to retain policy space. A number of countries, such as Kenya and Nigeria, have already instated some data localisation laws, leading to approximately 70 per cent of data traffic being localised in 2020 in these countries, compared to 30 per cent in 2012. But there is need for complementary policies supporting African digitalisation, including subsidies on electricity rates; improving internet connectivity; cyber-security, data processing and analytical capabilities through targeted skills-development.