Researching the history and culture of the Shan, the largest ethnic minority group in Myanmar, is possible in UK and US libraries where small well conserved, and cataloged Shan manuscripts are available. Researching in Shan State in Myanmar is more complicated. One can only travel in “safe areas” where there are no military incursions. Research relies on the good will of individual monasteries and private collectors. During one field trip I worked in the historic collection of a sick and elderly man who had inherited manuscripts through generations of his family. He asked if I could find a secure place for this precious collection before he passed away.

He had no confidence that such a place existed in Shan State. I knew a monk who was collecting manuscripts rescued from derelict and poverty-stricken monasteries and promised to contact him for advice. Before we had time to organise a visit, a dealer from Thailand approached the elderly man and made a fantastic offer for the collection. Later I heard the manuscripts had been torn apart with individual pages sold to home decorators in Bangkok who mounted them in frames for sale to tourists.

This story is an example of what happens to precious cultural artifacts in an unstable country ruled by the military (Tatmadaw). Ethnic groups, including the Shan, suffer continually from unlawful killigs, torture, ill-treatment, rape and sexual abuse, forced conscription, forced displacement, forced labour, but also the plundering of cultural artefacts, land grabbing and illegal extraction of minerals. In response armed Shan groups participate in sporadic clashes with the Tatmadaw.

For the Shan this is an ethnic conflict and not a religious one because the Shan are Buddhists, as are their oppressors. However, the form of Buddhism they practice is culturally distinct. The aim of the Tatmadaw in Shan State is to erase distinction and create a homogenous Burman society and an exclusively Burman form of Buddhism. This is why they attempt to erase evidence of Shan history. This can take the form of looting as happened in Yawngwhe. A spectacular teak palace, once occupied by senior Shan princes and their families for generations was raided. The palace housed a unique royal collection of Shan arts, crafts and historical records. One night it was plundered under cover of darkness and the entire collection transported in Burman army trucks, destination unknown.

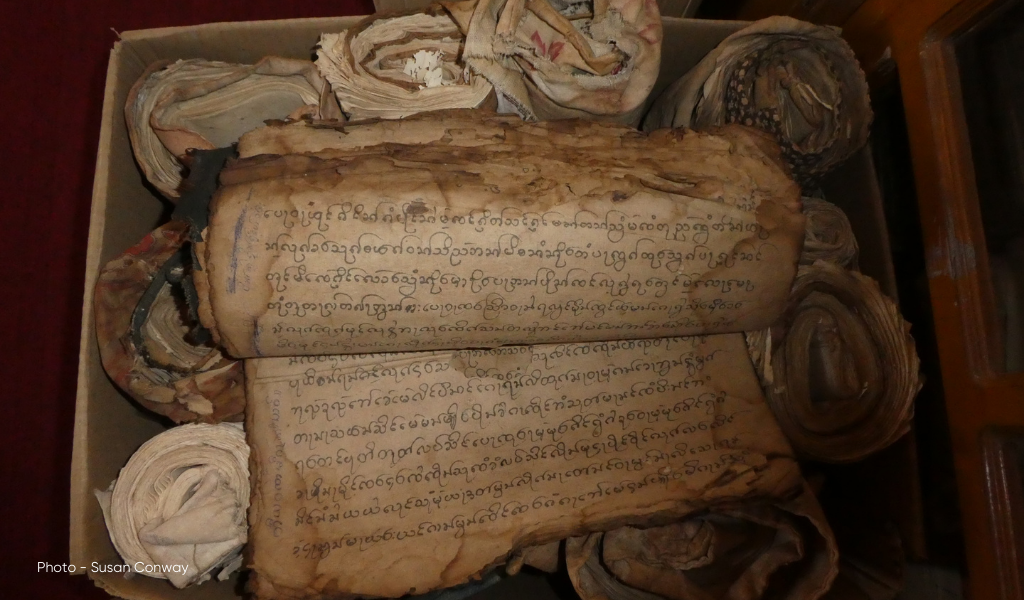

Included in the Yawngwhe palace collections were Buddhist manuscripts written in local scripts that recorded Shan Buddhist and spirit rituals, history, land records, astrology, cosmology, literature and medicine. Historical manuscripts describe how ethnic and religious groups in Myanmar functioned in times of war and peace. In peacetime they collaborated, including in the production of manuscripts. Shan and Lao, Burman and Yunnanese and Siamese (Thai) scripts in various combinations were written by monk scribes who were free to travel in peacetime. They moved easily throughout the country between ethnic regions. This inclusive version of history and collaboration among ethnic groups is of no interest to the Tatmadaw.

Today monks protect Shan religious artefacts from plunder as best they can. Many are in bad shape. Poorly maintained library buildings in monastery compounds contain manuscripts ravaged by insects and damaged by humidity. There are exceptions out of conflict zones where monks maintain records and conserve objects but that is not widespread. Impoverished Shan villagers living in an unstable environment, or fleeing military conflict often survive by selling Shan artefacts to foreign dealers.

Continued clashes between armed Shan groups and the Tatmadaw has not deterred international tourism. Until Covid-19 struck, Taunggyi, the capital of Shan state, and nearby Inlay Lake, were popular tourist destinations away from conflict. The military are present in large numbers but keep a low profile. In this more stable environment Shan State Buddhist University (SSBU) has established a campus with a newly built library. One floor is dedicated to Shan manuscripts and The Centre for Manuscript Studies. The Centre invites specialists to read and give advice on endangered scripts. The library is accepting manuscripts brought in by monks from conflict areas for safe keeping. There is a programme to create a digital library of the manuscript collection that will eventually be available for study online worldwide. Success of this whole project relies on continuing stability in the Taunggyi region.

That stability may depend on policies of the Chinese Communist Party as they emerge as a force in Shan politics. In 2019 delegates from the Belt and Road Institute attended the first conference on Shan cultural studies allowed in Taunggyi. Chinese Communist Party treatment of the culture of minority groups in their own country raises major questions. Will the Chinese as a super power in the region support protection of cultural heritage among the minority Shan or support the Tatmadaw as they work to annihilate Shan cultural heritage?