Toxic masculinity and everyday sexism create a hostile environment for women in technology workplaces and in online spaces. In an increasingly digital world the male-domination of technology design, software production, and digital content is a serious problem that demands urgent remedy.

To understand the negative experiences of women in technology spaces and what can be done to remedy the situation we interviewed women from eleven African and South Asian countries as well as many employers and funders. We focused on women working in open-source communities because they have been under-researched at a time when companies are increasingly committing to use open source software as part of signing up to the Principles for Digital Development.

The resulting report entitled Towards a More Gender-Inclusive Open Source Community was co-authored with my colleagues Becky Faith and Evangelia Berdou from the Digital and Technology research team at IDS has been published by the Digital Impact Alliance.

The role and experience of women in technology workplaces

Computer coding was originally a female-dominated profession both in the US and the UK. However as it became increasingly central to economic and social life it was re-gendered as male work. Today women are under-represented and underpaid in almost all technology workplaces, especially in senior positions, and the situation is far worse for Black women and LGBTQ workers. The few women that continue to work in these male-dominated technology spaces often experience discrimination and disadvantage.

Women that we spoke to had been told things like ‘go back to the kitchen’ and to leave technology work to the men. Others told us that they receive so much abuse online that it has become common practice for women coders to adopt gender-non-specific avatar names such as Alex or Max to reduce online abuse. Disguising their femininity was also an offline tactic to reduce discrimination.

“It is very different to join an all-male team versus one that is diverse. It goes back to the stereotype of male developers having a very masculine, ‘bro’ culture. It can be uncomfortable for women because of the jokes. It is hard to explain, but it is very different environment where you are not entirely able to be yourself as a woman. One of our other female coders wears trousers and acts a bit more masculine to blend in.” – Female Software Engineer South Africa

Female coders told us that coping with bro’ culture in their physical workplaces led some women to try blending in by adopting a more masculine dress code in the workplace, talking about male sports and war-gaming, and tolerating sexist comments. A South African interviewee explained how this bro’ culture was not just male specific but reflected white, straight, privileged class backgrounds – creating complex intersectional barriers to building genuinely inclusive and diverse workforces. She told us how she had to leave gender and culture behind when she entered the workplace and ‘morph’ into another identity to conform to the euro-centric and bro’ culture of the coding team. The constant ‘code-switching’ of language, appearance, and behaviour and coping with the casual racism and sexism was identified as a damaging form of emotional labour.

Tackling the hostile environment that women, Black and LGBTQ workers often encounter in male dominated and heteronormative tech workspaces is a considerable challenge that no employer has yet fully addressed.

Approaches to tackling gender inequity

There is however a great deal of excellent work going on to support women coders entering the field. Progressive employers, non-profit agencies, and funders are experimenting with a wide range of interventions, many of which are highly appreciated by female new entrants.

Perhaps the most common category of approaches include the provision of female role models, mentoring programmes, and training provision for women entering technology. These are similar to those often provided by self-organising women’s groups in African technology hubs including Asikana Network in Zambia and AkiraChix in Kenya. The annual Grace Hopper conference celebrating Women in Technology, and Rail Girls and Google’s Summer of Code were highly appreciated by those sponsored to attend. One attendee said that the positive lift that attendance gave her was enough to sustain her for many months after her return to her male-dominated place of work.

Some interviewees however voiced a need to also move beyond these discreet events to build more integrated and sustained approaches to tackling gender inequity in technology workplaces. The view was expressed that there was a need to go beyond selecting individual women to benefit from overseas events and to go beyond ‘counting women’ and ‘fixing women’ to also challenging men to change themselves and become part of the solution. Some interviewees were keen to address the root causes of unequal gender relations as well as treating the symptoms.

Analytical framework

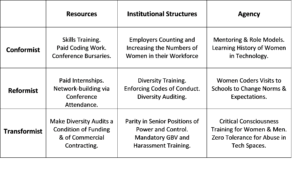

In response to these challenges we developed a simple analytical framework to differentiate between those kinds of initiatives that addressed women’s immediate practical gender needs and those that addressed their wider strategic gender interests. We found it useful to make a distinction between between conformist, reformist and transformist initiatives, understood in the following way:

Conformist initiatives help women to cope with the inequity of their gender role e.g. accessing resources such as training and income or mentoring support. These are highly valued and appreciated by women isolated in male dominated workplaces and may be necessary pre-requisites of other types of initiatives. In many cases these initiatives do not seek to challenge unequal gender norms and values – they do enable women to cope with and conform to existing gendered realities.

Reformist initiatives are designed to shift gendered norms and values in the direction of equity. Running diversity awareness training, designing and enforcing codes of conduct and having women coders teach in schools are some initiatives that seek to challenge normalised gendered relations and reform unequal gendered roles. In many cases these initiatives do not seek to challenge the unequal power relationship that give rise to and sustain the gender norms in the first place.

Transformist initiatives are designed to involve women in naming and shifting the power relationships that are the root causes of gender inequity. Transformist initiatives are truly empowering in that enable women to gain power and control over their work lives. This may involve women in senior decision-making roles, equal pay and influence, the removal of all forms of gender-based violence. Programmes seeking to transform the situation of women in technology workplaces will need to create safe spaces for critical dialogue to surface issues of gender, race and class that have been silenced by male-domination, white-supremacy and heteronormativity in the workplace in order to identify their causes and agree solutions.

The framework is only intended as a tool for thought. In reality many initiatives will cross the grid-lines and some will migrate between boxes over time and contexts. There is no claim that any initiatives should be discontinued in favour of others. All the initiatives illustrated have inherent value and ideally we need to be doing all of these things. There may however be value in assessing whether specific gender programmes or grant-making would be enhanced by including additional elements or working in additional sectors of the grid.

The framework is only intended as a tool for thought. In reality many initiatives will cross the grid-lines and some will migrate between boxes over time and contexts. There is no claim that any initiatives should be discontinued in favour of others. All the initiatives illustrated have inherent value and ideally we need to be doing all of these things. There may however be value in assessing whether specific gender programmes or grant-making would be enhanced by including additional elements or working in additional sectors of the grid.

We recognise that there is room to improve this framework and welcome your feedback and suggestions.

Tony Roberts on Twitter: @phat_controller