Earlier blogs in this series have addressed how the long-term success and sustainability of impact investing can be strengthened though increased participation and voice of investee enterprises, their employers, suppliers and consumers.

However, these groups face costs that constrain their ability to participate. Lack of money for child care and secure transportation, for example, can prevent women entrepreneurs from attending business training events, or stop employees from simply getting to their workplaces each day, let alone expressing their concerns to their employers over, say, health and safety conditions.

That there are real costs to participation is not news. But impact investors, donors and investees themselves have not yet confronted the question of how such costs should be addressed across their industry. It is time to do so.

Costs of participation are highest for employees, suppliers and consumers of investee firms

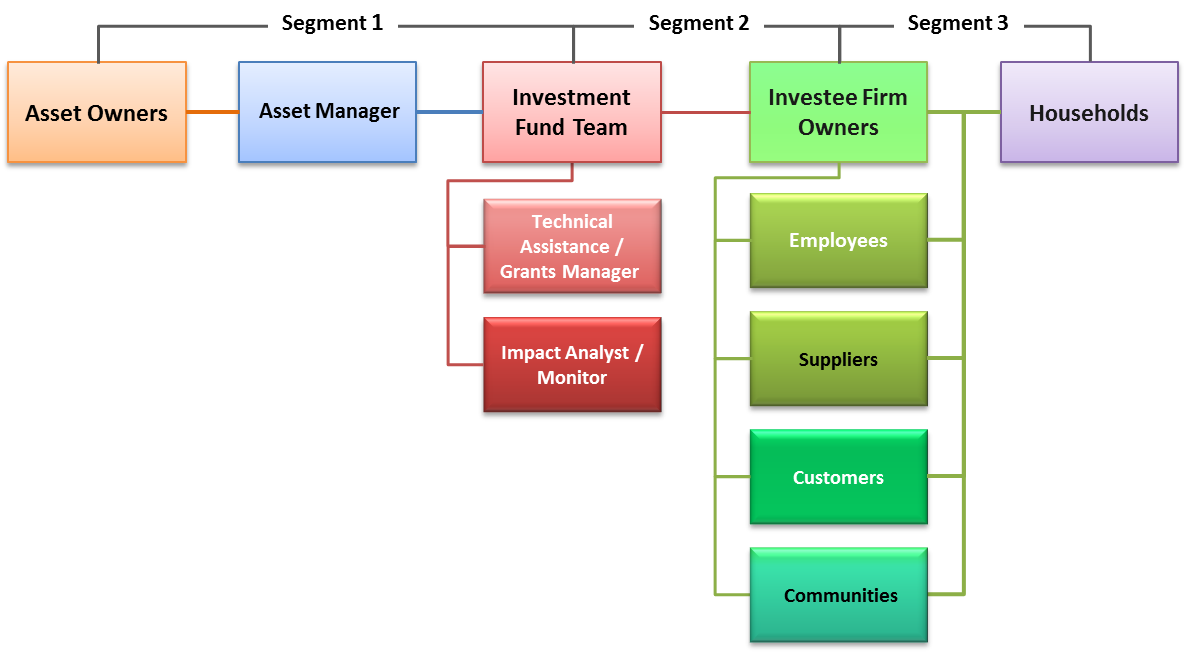

One approach to exploring this cluster of issues and what can be done is through the frame of the network of stakeholders involved in an impact investment deal. Figure 1 divides this network into three segments. In general, the asset owners, asset manager and investment team in Segment 1 are either well-off or very wealthy; they seek to safeguard or grow their capital and create impact, but their costs relate more to lack of time than money and their prime risk is reputational.

In contrast, the owners of investee firms, who span Segments 2 and 3, face a matrix of financial, time and reputational costs related to both their businesses and their families. At the same time, their participation can pay off, on the upside, in financial and reputational gains and, most importantly, contributions to development impact.

It is in Segment 3 where the costs of participation are most significant to stakeholders, especially employees, suppliers and customers, who are all likely to be living on modest or marginal incomes. When they are asked to participate in meetings on the investment project, they could lose paid time or incur direct out-of-pocket costs. Yet their ideas and commitment to the project are essential for its success. Of all the stakeholders in the network, this group best understands the impediments to social impact and how it can be most effectively realized.

Indeed, authentic engagement by Segment 3 stakeholders can add real value to the investee enterprise. In one tea estate in Malawi, for example, increased participation by smallholders was found to reduce local socio-economic inequality while thefts on the estate dropped by 80%.

However, the stakes are high. Each micro-level financial decision by a Segment 3 stakeholder carries serious consequences and trade-offs. Among the extreme poor, a farmer who attends a meeting on an irrigation infrastructure project on market day forgoes the opportunity to sell her produce. A worker laid off from a failed investee furniture company loses the ability to support his family.

The scenarios can be grimmer still. A start-up’s use of mobile money payments, fuelled by impact capital, may disadvantage powerful middle men who have long profited from the traditional cash-based system, and these middlemen may move to intimidate their new competitor. In this case, the start-up may need, in addition to financing, the political and logistical support of its investors to secure protection on the ground from lawless actions and allow the new business to operate freely.

Such threats may be directed, especially, at women challenging cultural norms, rival ethnic groups, gender-identity minorities or persons with disabilities. Investors engaging in consultations with these groups (particularly in the due diligence phase) could do more. One way is ensuring that consultations with these groups are done separately, and remain confidential and secure, with any out-of-pocket costs (e.g. meals, travel, child care) covered by the more well-resourced stakeholders.

Yet the costs of excluding community voices are also high for asset owners and asset managers. The failure to achieve social impact has repeatedly been linked to a lack of participation of the people these investments target.

The costs of participation in impact investment deals are thus borne unequally across the stakeholder network. However, there are effective ways and means of transferring funds from the wealthier stakeholders to those with less money and power that can meaningfully reduce this asymmetry.

Shifting the costs of participation to those with greater resources

Some lessons are emerging from gender lens investing. In Indonesia, for instance, with support from the Investing in Women Initiative of the Australian government, the Kinara Women’s Accelerator Program covers child care and other costs to enable women owners of small businesses to improve their business skills and knowledge and optimize the investment capital they receive.

And in Kenya, a gender equity grant to the Village Nut Company from Root Capital and Value for Women enabled the business, 60% of whose workers are women, to set up a daycare centre with music, art and educational activities, at its processing plant.

More generally, asset owners and managers can pay for technical assistance grants to hire facilitators and cover out-pocket expenses of Segment 3 stakeholders for consultations at key points in the investment cycle—especially front-end company screening and due diligence and back-end exit operations—to amplify voice and choice for investee-company owners, workers, suppliers and customers.

Impact investment projects can also fund and integrate gender-sensitive, participatory methods and tools into monitoring, evaluation and learning activities. In the development space, Southern think tanks like PRIA in India and Ghana’s Institute for Policy Alternatives have built proven methods and tools for participatory impact assessment, as have Northern organizations, such as the Institute of Development Studies.

As impact investing continues to grow and evolve, finding other effective and efficient ways of equitably sharing the costs of participation across the stakeholder network is important work. This is a time for bold thinking and creative experimentation. It is also a time to produce new manuals, webinars and knowledge communities to guide practitioners.

In its fullest form, the impact investment stakeholder network can be a multi-class, multi-race and multi-gender alliance, blending solidarity with business and managing their respective demands. Sharing the costs as well as the benefits, impact investors must stand with their allies.

Edward Jackson is Honorary Associate with the Institute of Development Studies, Senior Research Fellow at Carleton University and a consultant to foundations and development agencies on impact-investing evaluation, research and field-building. He thanks Peter O’Flynn, Grace Lyn Higdon and Emilie Wilson for helpful comments and suggestions.