Reginald Herbold Green (born 4 May 1935) died aged 86 early on Saturday 16 October at Madeira House Nursing Home, Louth. Reg was a development economist specialising in East and Southern Africa and was a Fellow at IDS from 1975 to 2000, when he retired.

Reginald Herbold Green was born in Walla Walla, Washington the son of a clergyman and professor, Reginald James Green and Marcia Herbold. He graduated summa cum laude from Whitman College which awarded him an honorary doctorate twenty years later. From Whitman College he went to Harvard where he gained his doctorate in 1961, thereafter joining the Economic Growth Centre in Yale University. This led to appointments in the universities of Ghana, Makerere University College in Uganda and in the Treasury of Tanzania from 1966-74, where he also served as adviser to President Nyerere and as Honorary Professor of Economics at the University of Dar Es Salaam. In 1975, he was made a Professorial Fellow of the Institute of Development Studies at the University of Sussex which served as his main base until his retirement at the end of 2000.

Reg, a development economist, produced an astonishing range and number of analytical and policy papers on African economic issues, especially those of Tanzania, Mozambique and Namibia and on what is now the Southern African Development Community (SADC). For seven years he was economic adviser to President Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, in the years when Nyerere was the darling of the donor community. In the 1980s, Green was a key economic adviser to SWAPO and the UN Institute of Namibia during Namibia’s run up to Independence in 1991.

Reg was a committed Christian, highly conscious of the often-ignored ethical dimensions of debt, trade, aid, North-South relationships and political liberation more generally. He made many contributions to the World Council of Churches. His early book, Unity or Poverty: the economics of Pan Africanism, published by Penguin in 1968, made the case for African countries to coordinate or join together as a key condition for development. But in the immediate aftermath of Independence, the message fell on deaf ideas – though the general point always motivated his work on trade and development within the regions of East and Southern Africa.

Reg wrote over 500 published professional articles (including many IDS Bulletin articles), papers, book chapters and books. His first major academic paper was given in 1960 to the West African Institute of Social and Economic Research Conference in Ibadan. He always maintained a broad perspective and range of interests – seeing himself as a servant of African goals and objectives but one willing to use every ounce of his talents and creative imagination to provide professional analysis of how best to achieve them.

One of his major and most creative contributions was commissioned by UNICEF. This was to estimate the cost of the destabilisation policies of South Africa’s apartheid regime in the 1980s, especially on children in Mozambique and Angola. Although often denounced in political terms, it was only when Reg Green turned his creative mind to serious accounting that the brutal economic and social costs were brought home to the world. The resulting publication, Children on the Front Line (1987) provided detailed estimates showing that more than two million under-five children in Mozambique and Angola had died as a result of South Africa’s destructive economic and military policies targeted on these countries. The study was cited with approval a number of times in the US Congress and helped bring a change in Western support to the apartheid regime of South Africa.

Life at IDS

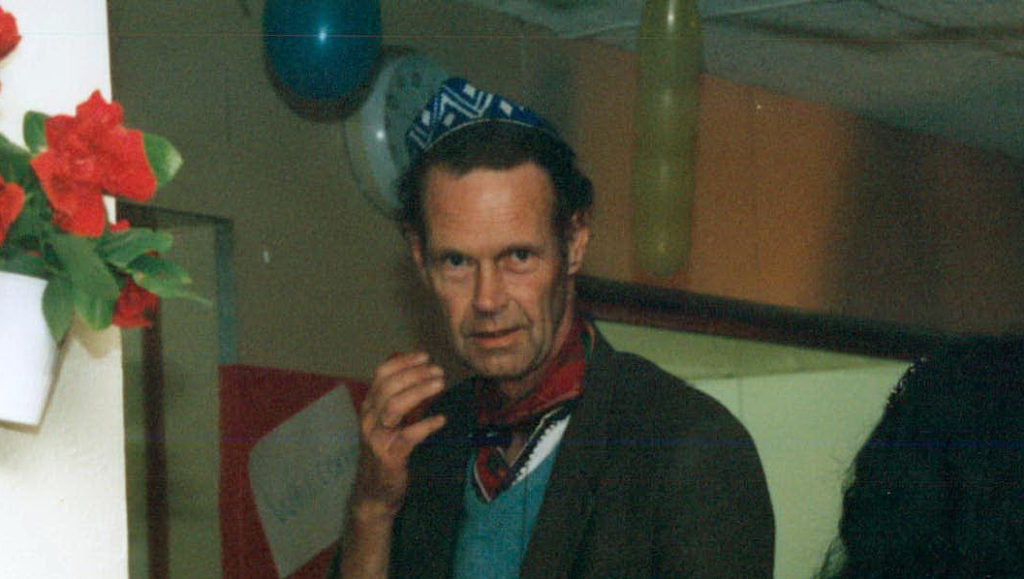

Of all the fellows to have worked at IDS, Reg Green has been the most prolific as well as in behaviour the most bizarre. No IDS pantomime of the time was complete without some student brilliantly mimicking Reg to howls of laughter. While commanding respect and admiration, support and only occasional exasperation from his friends, he often generated offhand dismissal from those who didn’t bother to read his articles. Strangers reacted instead to his whooping laugh, his head topped by long hair under a small Muslim cap and his colourful neckerchiefs tied with a cowrie shell knot.

In his later years, when he lived in Lewes, his gangly frame, hunched over and supported by Tanzanian walking sticks on both sides was instantly recognisable – and widely recognised. A Lewes jeweller by Cliffe Bridge even displayed an oil painting showing Reg Green peering in the shop window.

His 26 years at the IDS gave him freedom and opportunity for a succession of continuing involvements mainly in Africa, though also in the Philippines. As adviser or consultant, his involvements covered most countries of East and Southern Africa, the Economic Commission of Africa, UNICEF, ILO, IFAD, WFP, UNCTAD and UNDP. For a number of years, he played a major economic role with SADCC, the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (which today continues as the Southern African Development Community).

At times, he also served on the Advisory Group on Economic Matters of the World Council of Churches, as a trustee of the International Center of Law in Development and on the Education Committee of the Catholic Institute for international Relations. He played a major role in the UN Institute for Namibia as well as serving as consultant to the ACP Secretariat, the Commonwealth Secretariat and to the African Centre for Monetary Studies.

Reg had a phenomenal memory, with apparently immediate recall of almost everything he had written, much of what he had read, as well as many other matters important and trivial. In the mid-1970s, the Overseas Development Association (ODA), now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), was considering re-establishing aid relationships with Tanzania. Reg Green was invited for a consultation. This lasted for almost a day, with two stenographers taking turns to capture Green’s detailed statements at breakneck speed– ending with some 125 pages of type-written notes.

In the 1980s, as African countries suffered under the tough and enforced conditions of structural adjustment from the IMF and the World Bank, Green became a trenchant critic of adjustment policies, but was always careful to suggest positive alternatives. In the 1980s, as civil conflict beset many African countries in Africa and elsewhere, Green turned his mind to the political economy of conflict and post conflict rehabilitation, working with Professor Bayo Adedeji on an African led Project for Comprehending and Mastering Conflict. His concern with poverty reduction, liberation and broad-based development were connecting threads through all his writings from the 1960s to 2000, when at the UN Millennium Summit, heads of state adopted the Millennium Development Goals for poverty reduction on a world-wide scale.