How should community voice be incorporated into impact investing? And what practical applications can impact investors do today to start thinking about participatory ideas? In our last blog, we began to identify opportunities for greater participation of the populations impact investors intend to support. In relation to this, asking oneself, “Who defines and sets the terms for impact in our organisation?” seems to be a good starting point.

Impact investors have done a lot of good (and some bad) so far, but mostly on their own terms. From a “return on investment perspective,” this makes sense: they have the capital, the knowledge and the means when it comes to “investment”.

However, even with this perspective in mind, incorporating participation affords an opportunity to receive feedback from a larger range of stakeholders with better local knowledge and consequently safeguard against financial and social impact risks.

Engaging community stakeholders with practical questions throughout the investment process can inform, shape, support and improve an impact investment. As a result investors can ensure there are real social benefits to keep the investee business in operation; it’s all hypothetical until confirmed by the communities.

Establishing a common understand between global development and impact investment communities

To that effect, we need to establish a common understanding between the global development community and the impact investment community by introducing impact investors to participatory values, language and principles as well as introducing development professionals to the language and concepts behind the investment cycle.

And there is a lot of language to cover!

Getting terms right will ensure that these communities of practice do not live in confusion – or ignorance – of each other. While recognising the power definitions have, and how in an effort toward simplicity we risk becoming reductivist, we welcome further debate on terms which allow us to get deeper into these issues.

Firstly, what do we mean by participation?

As discussed in our last blog, participation refers to processes within which specific methods are used to enable people to influence decisions which affect their lives. In terms of impact investment, what does it mean for investors to support people to have more control over their economic futures, and how might investments do this?

Participation has been interpreted by development practitioners in many different ways over the four decades since participatory practices were first introduced in the 1970s, in part with the adoption of Participatory Rural Appraisal (PRA) created by IDS Research Associate, Professor Robert Chambers.

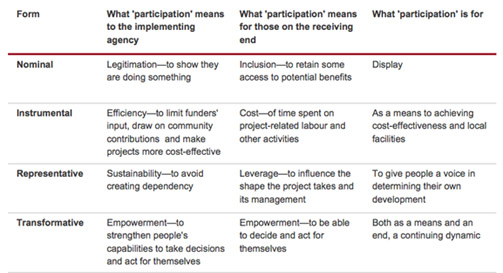

Participatory methods now run deep in contemporary approaches from project planning to community engagement such as human-centered design. Participation can occur at different depths and this been conceptualised by first by Sherry Arnstein in 1969 as a “ladder of participation” (PDF) and adapted by subsequent authors.

In her “ladder of participation” (see below) Professor Andrea Cornwall illustrates the progression of participatory processes from nominal to transformative.

Facilitating a greater participatory role in impact investing would mean that people’s voices would not just be ‘heard’ during the design and implementation of a project but also their preferences can shape the overall outcomes of that investment.

This is a useful table to investors (and their investees) to think about how they currently engage with their communities. If they are only engaging with communities for display, or nominal compliance, than they may not be getting the advantages that incorporating community voice would bring.

Secondly, what are some definitions of impact?

A technical definition of impact provided by the OECD Development Assistance Committee (PDF) states that impact is any “positive and negative, primary and secondary long-term effects produced by a development intervention, directly or indirectly, intended or unintended.”

As impact investing has become more sophisticated, the industry has moved more towards thinking about the negative impacts of their investments.

“Social impact” is the term used by finance community to describe “the effect of an activity on the social fabric of the community and well-being of individuals and families.” We’ve found that it is most commonly used to describe concepts Team Global Development might call outcomes and/or results (typically job metrics).

In reference to the ladder of participation above, we believe that in order for an investment to be safe, effective, and just, investors should incorporate participatory processes that are representative or transformative into the impact investment process in order to affect lasting social change.

So, what exactly is impact investing?

The most common definition of impact investing is an investment “made into companies, organisations, and funds with the intention to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact alongside a financial return.”

A financial return in its most simplest definition is a monetary profit, which may include interest payments on debt or dividends on stocks.

Environmental, Social, or Governance (ESG) returns refer to outcomes referring to the sustainability and ethical effects of investing. Investors engaging in ESG considerations are not considered impact investors per se, as the objective is typically to ‘do no harm’ as opposed to impact investors intentions to generate social change. ESG investing can be seen on the continuum of investor engagement for impact.

Impact investing goes further by specifying specific impacts prior to making an investment, be they related to a specific theme from the investment product, such as climate change adaptation, to a more general theme such as job creation in low-income areas.

Typically investors look for a strong theoretical underpinnings of their social impact which has been referred to as an investment thesis (similar to a mission statement for Team Global Development).

Impact investment differs from a few other investment approaches in the following ways:

- “Intention to generate a measurable, beneficial social or environmental impact” as per the previously cited definition, this includes a clear articulation of the types of impact that the investor is trying to make.

- Return expectations can differ depending whether funding is concessional or non-concessional. Non-concessional investments expect a market rate return, generating a profit that can be found in the wider financial market, while concessional will forego some financial profit in order to prioritize a social outcome.

- Impact may be aligned to a particular focus (i.e. youth employment), target area (i.e. sub-Saharan Africa), or even sector (i.e.infrastructure, green energy, agriculture). Impact investors align themselves with certain themes of investment in this manner, with the impact that is wanted to be created aligned with those themes.

- Who invests, and whether the investor has a social/philanthropic mandate for impact.

These features can be quite broad, meaning that there are some legitimate concerns by those in the development space that Impact Investing can just be considered to be window-dressing for traditional neo-liberal finance as well as concerns for “Impact Washing.”

Participation has also been subject to the similar co-optation, and we will discuss both types of ‘washing’ in a later blog.

The Impact Investment Process

Investors typically have a portfolio of different investments they put capital (their money) into. These span across several different asset classes which can be stocks, bonds, or private equity investments (private equities refer to people exchanging pieces of companies through private transactions and are common in impact investment).

Investors aligned to social impact may split up their portfolio towards those that they consider “impact investments” against those that are standard investments.

Both types of investments appreciate and depreciate in value, and can be bought and sold from different actors.

Four takeaways for impact investors

- Definitions: who is defining your social impact? What role could your beneficiaries/target populations play in defining social impact?

- Stakeholder analysis: can you start from your beneficiaries and their service requirements and work forward from there instead of the other way around?

- Risk analysis: what are the key risks in your portfolio stemming from a lack of representation from the community? Are these operational, strategic, financial, or reputational?

- Returns: can you reframe ESG returns as ESG-P returns? With P standing for how participatory your investments are?

We note that active private equity investors (i.e. those with regular interactions with their investees) can be the harbingers in the first instance to promote participatory themes amongst their investees.

In our next blog, we outline the typical investment process that an impact investor may undertake to find the right deal, invest and exit and identify entry points for participation within the investment process.

Further Resources

- To learn more about participation, IDS has recently released a Participation Primer in partnership with Open Society Foundations new Economic Advancement Programme.

- A fantastic resource for further information on impact investing is the Impact Management Project, which has a full glossary of terms.

- A resource that pays greater deference to the language of development is the Evaluating Impact Investing website, developed by Karim Harji and Edward Jackson.

Images: 1) Illustration of community participation by Victoria Francis (CC BY-NC 2.0); 2) Ladder of participation table, recently published in this primer on Participation in Economic Decision-Making; 3) image of the impact investment process by G. Lyn Higdon (IDS).