Next month sees the inaugural Digital Development Summit 2017, and following last week’s blog on why the future of work in a digital age matters for development actors, here is the next in the series, by ODI’s Abigail Hunt, drawing on her recent report ‘A Good Gig?’

The world of work is changing fast. There is an enormous lack of quality jobs. Recent analysis by the Overseas Development Institute suggests two billion people are outside the labour force, of which two thirds are women, and many of whom want to work.

The world of work is changing fast. There is an enormous lack of quality jobs. Recent analysis by the Overseas Development Institute suggests two billion people are outside the labour force, of which two thirds are women, and many of whom want to work.

Rapid developments in technology, digitisation and automation have brought an increased urgency to understanding how labour market outcomes are changing. Making sure these trends support, rather than hinder, the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals is critical – but not a given.

That’s why it’s great the development sector is slowly realising that more attention needs to be paid to the future of work. Current efforts to support sustainable livelihoods and reduce economic inequalities will need to be refocused to make sure they are effective in the face of huge change.

But these efforts must start now. It’s not just a question of projecting into the future – huge shifts are already underway and having real effects on people’s lives. Ensuring these effects are positive requires immediate action, before it’s too late.

The ‘Uber-isation’ of domestic work

One such trend is the global ‘Uber-isation’ of work. This has seen technology-focused companies – such as the widespread Uber transportation network company – bring together workers and the purchasers of their services, altering consumption and employment patterns globally.

Already well established in the US and Europe, ODI’s recent research demonstrates the ‘gig economy’, or ‘on-demand economy’ as it is also known, is also expanding fast in developing countries. Some Indian companies are growing by up to 60 per cent month on month. This is driven by increased digital connectivity and financial services, as well as an increasingly tech-savvy and affluent middle-class keen to benefit from cheap services at the touch of a button.

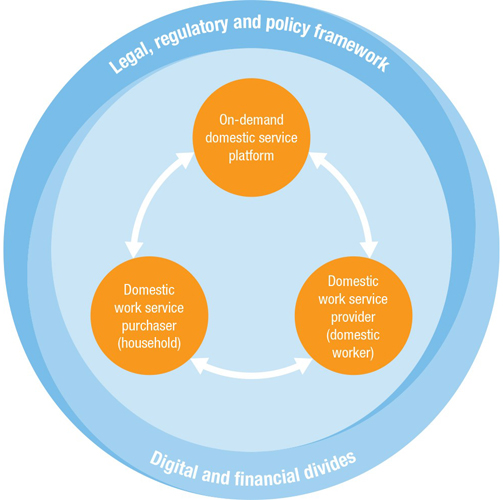

Our study explored the rise of on-demand domestic work platforms, considering the relationship between the company, worker and service purchaser as well as the surrounding legal, regulatory and policy framework and the implications of digital and financial divides (see Figure 1). Given the informality, insecurity and, in too many cases, exploitation and abuse experienced by domestic workers, any new development which could disrupt these working conditions merits close attention.

Figure 1: Study entry points (Source: Hunt and Machingura, 2016)

We identified a range of promising aspects of the on-demand platform models, which may be of particular benefit to workers in countries where the domestic work sector remains highly informal and unregulated. These include:

- Ability to track hours worked and earnings on the platform apps

- Ability to set own hourly rates

- Ability to work flexibly and to own schedule

- Company efforts to overcome digital and financial divides, including providing bank accounts or embracing low-tech means of engaging, communicating with and paying workers

Yet we also identified low and insecure incomes, discrimination, further entrenchment of unequal power relations within the traditional domestic work sector, and the erosion of established labour and social protections. Overall, the emergence of the on-demand economy threatens domestic workers’ access to decent work.

A short animation based on the research that explores how the rise of Uber-style apps is changing the working lives of women who are domestic workers.

Where next?

The rapid growth of companies means these new, technology-enabled ways of working are becoming increasingly deep-rooted. So what next to raise standards and ensure a fair deal for workers?

We think the answer lies across several groups – here’s a snapshot.

Governments need to ensure that legal, policy and regulatory frameworks are fit for purpose in the gig economy era. Much of the conversation so far has focused on the need to clarify labour law and whether workers are ‘independent contractors’ or employees. While addressing regressions in working conditions as a result of flexible contracting models is undoubtedly urgent, the gig economy requires a wider approach. This means supporting the potential of digital platforms to facilitate workers’ access to economic opportunities, while protecting against challenges to decent work.

Government responses should support digital and financial infrastructure and inclusivity, increasing women’s empowerment by supporting women’s expanded agency and control over their economic lives, social protection and the development of progressive taxation systems. Equally important is recognising the right of workers to organise and establish dialogue, collective bargaining and advocacy to draw attention to their experiences and, thereby, hopefully, improve conditions.

Gig economy companies also have a critical role to play. Ensuring their business model supports empowerment and decent work is the most important first step, but they can also innovate to design positive features into platforms, such as safety buttons or two-way ratings systems that allow workers to rate clients.

Workers must have choice and agency over their working lives for the gig economy to be a truly empowering experience, and dialogue aimed at securing fair corporate practice is central to this. Yet the emerging platform cooperative movement casts doubt on how far the current model can ever deliver for workers.

In response, worker cooperatives are developing their own platforms. For example, Up&Go domestic workers in the US own and control the business and platform technology. In developing countries too, this could be a serious option. Kenya, for example – where 63 per cent gain their livelihoods directly or indirectly from cooperative-based activities and internet usage is amongst the highest in Africa – may be well-placed to lead the charge in worker-led platform cooperatives.

The gig economy has already arrived. What do you think needs to happen to ensure it evolves to the benefit of all, including for those who currently stand to gain the least from it?

Abigail Hunt is a Senior Research Officer within ODI’s Growth, Poverty and Inequality Programme specialising in women’s empowerment and gender equality.