Contrary to its practice to date, as of 2018 the European Commission’s engagement policy with sub-national entities will no longer conflate ‘local authorities’ with ‘civil society organisations’. This change, recently agreed by the European Union, emerged as part of a reflection on how to engage on urban issues. In effect, it means that local governments have gained recognition as an intermediary step between national governments and civil society organisations.

To me, the shift is far from anecdotal. It shows how profoundly subversive the whole urban agenda can be, with cities increasingly claiming their right to self-determination. Is power fragmenting before our eyes?

Knocking on open doors

To be sure, the New Urban Agenda (NUA) – as inclusive as the process was said to be – was eventually adopted by states in October 2016 in a classic United Nations process. States, in a way, were thereby asserting their sovereignty over ‘their’ cities. But consider this statement made at the time by Emmanuelle Pinault, Head of City Diplomacy at C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group: ‘There are many good things in the New Urban Agenda, but nothing really new or innovative compared to what mayors have been doing for years.’ Indeed I wonder how much traction the NUA has among cities themselves. My guess is that the impact it could currently be having on donor policies is not matched by its relevance, let alone its transformative power, for cities themselves. At the moment, whatever global urban policy there is could be running behind urban practices, not necessarily shaping them. And this, perhaps, is a positive consequence of decentralisation.

A similar paradox affects the Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development. Goal 11 aims at making ‘cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable’. The goal is declined in targets referring to housing, transport, urban planning, cultural heritage, disaster preparedness and response, pollution, and green spaces. It is often dubbed the ‘urban SDG’, even though urban advocates like the Cities Alliance vehemently oppose this label, arguing that all Sustainable Development Goals are relevant to cities. Goal 11 also implies that it would be the national government’s responsibility to ensure these targets are met. But doesn’t this chain of responsibility run counter to the basic idea of decentralisation?

Who’s in charge?

Indeed, there is an inherent tension between the global ambitions of the NUA and SDGs, and the local decision-making underpinning decentralisation. Decentralisation is effectively about power redistribution. It is a professed goal of many donor agencies working to promote good governance (noting that at home, the same governments are often also feeling pressure to centralise services in response to neoliberal ideas of rationality and cost effectiveness). If national governments and donor agencies were consistent in their pursuit of decentralisation, then a global urban policy should probably be restricted to two things: (1) endorsing the right of cities to self-determination, expressed through service delivery and revenue collection, but also (2) subjecting cities to international human rights standards. Cities could then, if they wished, adopt the goals and targets enshrined in Agenda 2030 and similar documents. The voluntary commitments taken by several cities to uphold the standards of the Paris agreement on climate change show a precedent of such developments. Beyond this, global urban policy should refrain from enunciating standards of service delivery or setting priorities anymore than it does for states. Let cities be, let them decide on their own internal priorities.

This is not to say of course that cities cannot and should not learn from each other. But this is a matter of practice, not policy. And this is where research institutes and practitioner networks have a key role to play.

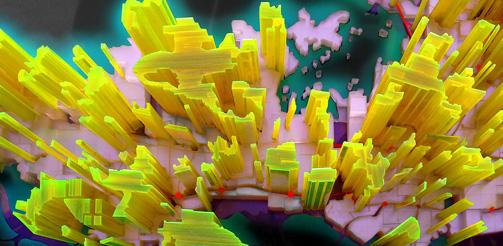

Image: ‘Mars in Mumbai: Prototypes of change developed for the BMW Guggenheim Lab’. Credit: Nevill Mars on Flickr