The act of murder is incomprehensible to most of us. We consume murder mysteries and detective stories on screen and in books, trying to understand the motivations and tipping points that lead someone to take another life. But when it comes to femicide — the killing of women and girls because they are women — words often fail us.

Femicide, specifically, is the killing of a woman or girl because of her gender. It is considered a form of murder due to the gender-based motives that drive it. Killing can occur for various reasons, such as accidents, self-defence, or situations where there is no criminal intent. Murder specifically refers to an unlawful killing with intent or premeditation.

In Vietnam, there is no specific term for femicide. The phrases used are việc giết phụ nữ and phụ nữ bị giết, which translate to “the act of murdering women” and “murdered women.” This linguistic gap is one of the findings of our research project White Bowls, Lost Souls, which aims to improve reporting on intimate partner femicide, inspire reflection on gender-based violence, and encourage action to end it. But translations are hard and without the right words, how do we even begin to address the issue?

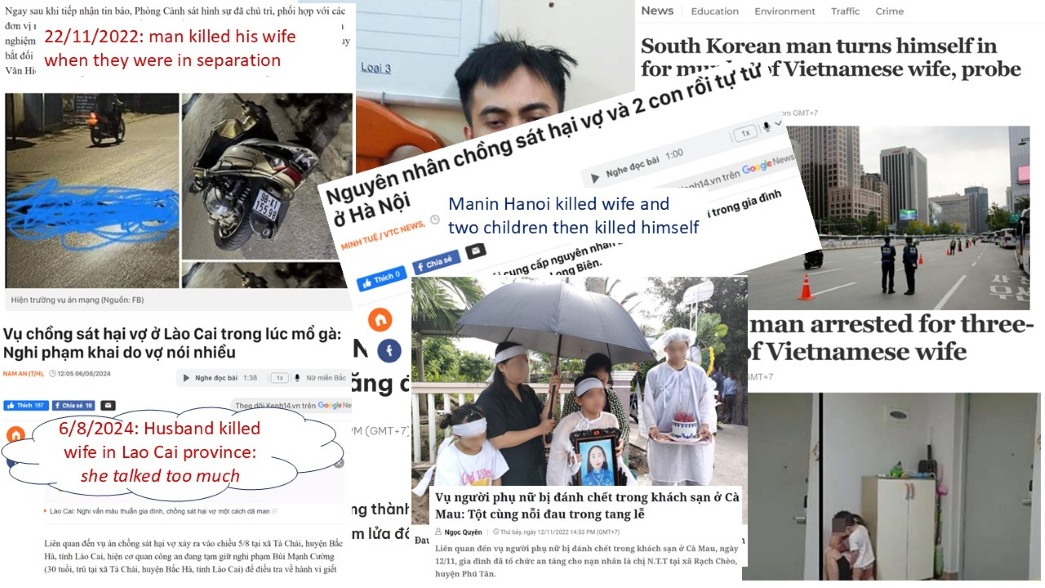

To gain an initial understanding, we conducted a media analysis of reports from three major national online newspapers—VietNamNet, Tuổi Trẻ (Youth), and Phụ Nữ Việt Nam (Vietnam Women’s Union online publication)—from January 1, 2018, to December 31, 2023. Our findings reveal that Vietnam follows a global pattern of femicide – an escalation of gender-based domestic violence.

- Intimate partner femicide is the most common form, with many women killed by their husbands in their own homes.

- The most frequently used weapons are knives, swords, and other sharp objects.

- Suffocation, including strangulation by hand or with objects, is also a commonly reported method.

- Perpetrators can face severe legal consequences, including the death penalty or life imprisonment, but some take their own lives before facing justice.

- Media reports often lack in-depth information on the circumstances leading up to these deaths, including the frequency and severity of prior violence.

Understanding the pathways to femicide

Research shows a strong link between domestic violence and femicide: domestic abuse, coercive control, or stalking were present in over 90% of intimate partner homicides Identifying patterns shared worldwide and those unique to specific cultures is a key goal of international femicide research.

Extreme domestic violence often happens behind closed doors, with women maintaining a brave facade for themselves and their children. Nobody notices — or perhaps they pretend not to see. But why do women stay silent? Why do they not leave? Is it an act of defiance — “I will not be broken”- or an act of fear — “If I speak out, I will suffer more”?

In Vietnam, the concept of symbolic pride helps explain this silence. Symbolic pride refers to the feelings of satisfaction, honor, and glorification associated with both enduring and committing violence, which are considered noble actions to achieve social or political goals and rewards. Many women persist in silence, enduring violence in an attempt to hold their families together. They may also risk their lives by trying to leave. Research by Jane Monckton Smith in the UK and others shows that threatening to leave an abusive partner is one of the most dangerous moments for a woman. Many women stay because leaving means risking death. And if they die, what happens to their children?

Recognising the warning signs

Are there warning signs before a woman is killed by her partner? Were there indications that she was in greater danger than others facing domestic violence? Research in other countries suggests that strangulation or suffocation as a form of violence is linked to a higher risk of being killed.

We need to document to recognise patterns, to visualise the unthinkable — the act of taking a life. Social change requires more than just accurate information; it requires affective engagement, the ability to feel and act. Affective engagement is a powerful tool for learning and interaction design. Translating research findings into music can reach engage young people who may deeply care about a topic but not read research papers about it. When scientists and artists collaborate, they can combine factual and emotive approaches to engage citizens, the state, and civil society.

As Martin Luther King Jr. said, “In the end, we will remember not the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.” Responding to symbolic violence requires more than words because symbols operate beyond language. White Bowls, Lost Souls explores this through evidence-based documentary, ceramic installations, and performance, which challenge and reshape dominant narratives through materiality, movement, and presence. These artistic interventions offer tactile, visual, and embodied counter-narratives that words alone cannot convey.

We can respond in many ways, but we must not be silent.