Following Foreign Secretary David Lammy’s visit to Beijing as part of an effort to normalise relations, we need to think through reengagement with China on global health and development. This is important given the background of huge global challenges and a contested international landscape that is constraining progress on these issues. There is a strong foundation for cooperation, but a need to identify priorities for working with China to meet the UK’s global ambitions, and to increase UK capability to support this.

The UK’s 2023 Global Health Framework articulates a vision for a healthier, safer and more resilient world, a cornerstone of UK security and prosperity. It touts UK leadership in science and technology and an ambition to be a leader in strengthening global health and resilience to future threats.

Covid-19 has set back progress in global health and shown the need for stronger frameworks to deal with mutual challenges, including future pandemics, antimicrobial resistance (AMR), climate change and ecological degradation, and the governance of emerging technologies, including AI.

Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals and Universal Health Coverage is off track, with little prospect of meeting 2030 targets, and financing for global health faces strong headwinds. Major funds, including the World Bank’s International Development Association, Global Fund, and new entities like the Loss and Damage Fund are seeking over $100 billion from donors. Mounting debt and liquidity issues are creating the conditions for de-development for many countries – a situation that benefits no one.

Simultaneously, though, technology is changing global health possibilities, through applications of AI to health, strengthening health systems using digital health, or innovative biopharmaceuticals, particularly in oncology and antimicrobials. But these all come with the need for international cooperation.

China’s complex, evolving role in global health

UK policy rightly recognises that improving global health must be a cooperative endeavour. Yet, as the World Economic Forum states, cooperation on global challenges is at a geopolitical inflection point. We face the challenge of ‘managing a volatile risk landscape in a low cooperation world’, characterised by shifting power and competition over key technologies and the nature of the international order.

China is now fundamental to the global system in a way it hasn’t been before – including in global health and development. How the country strengthens its domestic health system, for example, and manages infectious diseases, antimicrobial resistance, NCDs and ageing is globally significant. And how it engages in multilateral efforts on pandemic preparedness and AMR – including to develop new antibiotics – will be crucial to their success.

Similarly, how China prioritises its spending matters for global health financing. How its assistance develops, and how it engages with indebted countries matters not just for those countries’ balance sheets and health spending, but for traditional donor countries’ assistance to those same countries.

China is also increasingly important in health technologies. Chinese-supplied pharmaceuticals support health systems worldwide, and the country increasingly leads in cancer therapeutics, AI and digital health. Some Chinese technologies will be essential to both high- and low-income countries alike, while in areas like immuno-oncology China is likely to compete directly with developed countries’ pharmaceutical and biotech industries.

Global health and UK China policy

The UK’s development assistance and contributions to organisations like WHO need to consider how China allocates its development funding. That means better understanding China’s Development Assistance for Health, the intersections with the Belt and Road and Global Development Initiatives, and China’s engagement in emerging and newly-strengthened fora, such as the enlarged BRICS.

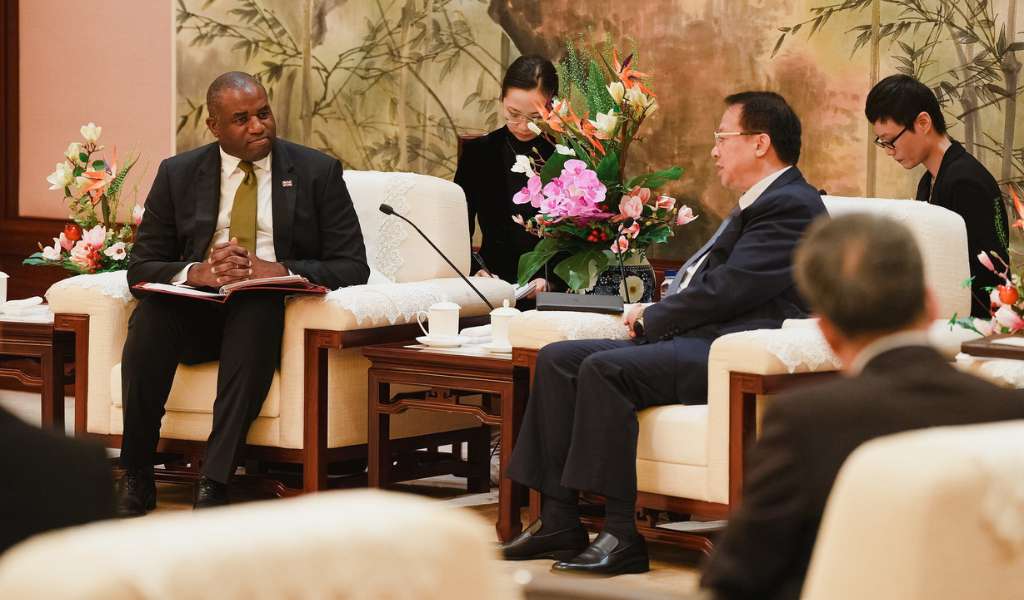

Inevitably, UK policy towards China will remain complicated, involving a mixture of cooperation, competition and disagreement. But a return to predictability is needed, following chaotic swings over the last ten years. David Lammy’s recent visit provides an opportunity to rethink how constructive relations on global health should look. China partners with other G7 countries on this and, despite strains in the bilateral relationship, has goodwill towards the UK – a recognition of UK strength in this area and a history of collaboration.

We now need a clear assessment of what the UK wants from this relationship, based on understanding how China intersects with UK policy priorities and that engagement has upsides, challenges and possible risks. It means recognising that all countries’ global health strategies are part of their foreign policy and soft power projection, and that we will be competitors and rivals in some areas, as well as cooperation partners in others.

Strengthening research and policy on China and global health

Developing a strategic approach to engaging China on global health requires seriousness and investment at home – the UK has limited understanding of China’s place in global health and limited capacity to engage. A recent joint Institute of Development Studies and King’s College London Roundtable concluded that we need to strengthen the research and policy ecosystem on China and global health. That means investing in homegrown capability to better understand what China is doing, where it is coming from, and the opportunities for constructive engagement.

This dovetails with the government’s China audit and Lammy’s call for a ‘progressive realist’ foreign policy. China is not going away, and the bilateral relationship will continue to fluctuate. Lammy’s recent visit included discussion of the need to work on development and global health. Figuring out where our priorities for engagement lie and building our capability to engage effectively is now necessary – the ball is now in the UK’s court.