The unprecedented scale and extent of the global cholera upsurge presents a challenge for effective disease control efforts worldwide. Not only are there more outbreaks, but they are also larger, making them more difficult to control without the standard two-dose vaccination regimen, which has been suspended since October 2022 because of shortages.

Africa remains the most affected region, with 17 countries reporting cases during 2023 and several being classified as acute crisis (Ethiopia, DRC, Tanzania, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Mozambique) recording an ongoing increase in confirmed and suspected cholera cases and increased case fatality rate (CFR). As of 15 January 2024, Eastern and Southern Africa have reported over 200,000 cases and 3,000 deaths.

Since a new cholera outbreak was declared in Zambia on 18 October 2023, 9,953 cases and 375 deaths have been reported. Nine out of ten provinces are affected with Lusaka having the highest caseload followed by the Central and Southern Provinces (SOURCE RCCE TWG). More than 50 percent of reported cases affect children under the age of 15, and children aged between one and four account for an unusually high number of cases (24 percent).

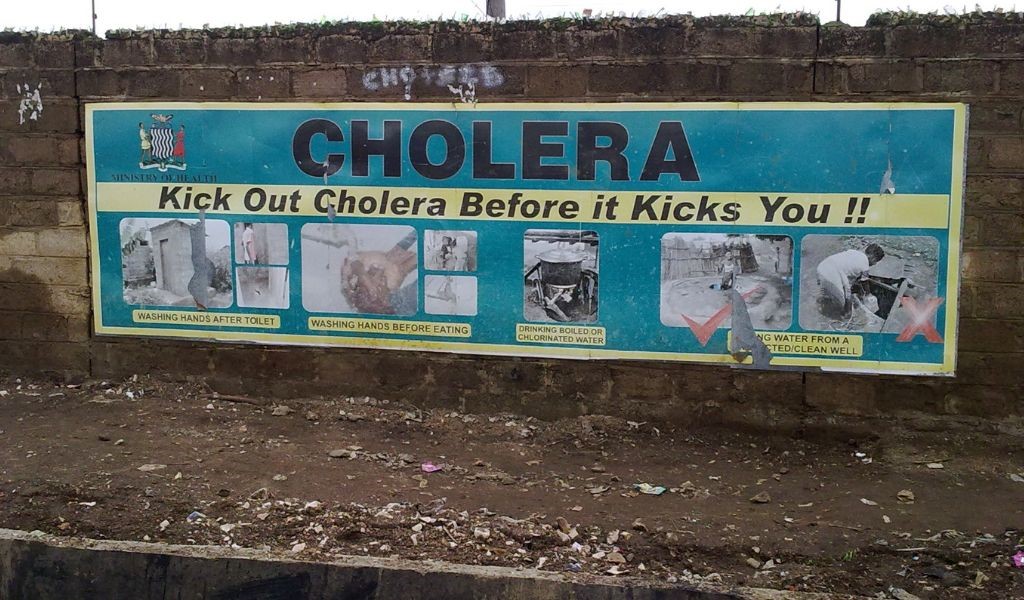

The current outbreak is driven by several factors, including cross-border movements, inadequate access to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure and services, population mobility between Lusaka, mining areas, and other parts of the country. Additionally, heavy rainfall and flooding, compounded by high water tables, increase the risk of contaminated water sources.

The rapid increase in cases has put a burden on the local health care provision for other essential services including outpatient and inpatient care, redeployment of health staff and supply shortages. To reduce the burden on local health facilities, Zambia’s Government has designated Lusaka’s National Heroes Stadium as a cholera treatment facility. However, capacity is overstretched, and many patients are brought in death. Additionally, it is estimated that the number of deaths in the community is higher than reported.

The Zambian Government, supported by WFP and its partners, is mobilising efforts to scale up the response, including the launch of the Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) campaign, provision of safe drinking water, community outreach and surveillance and the plan to strengthen all response pillars including risk communication and community engagement (RCCE). To improve prevention and risk-reduction behaviours and practices, partners have identified rapid and applied research as a priority to understand delays in seeking care, risk perceptions, myths and misconceptions.

A community-centred learning approach

Whilst the Global Taskforce on Cholera Control recognise community engagement amongst a package of measures to control cholera that also include surveillance and detection, case management and infection and prevention control, and access to WASH, more efforts are needed to support those managing and delivering responses at field level to implement key community engagement actions.

Community-level actions driven by local risks and vulnerabilities

Inclusion must be emphasised by supporting and improving community-level strategies and actions to reduce transmission risks. As people most at risk of infection may vary by context, assessments of vulnerabilities are needed to understand who should be engaged and how. For instance, the assessments may point to the need for engagement activities in multiple languages using different channels and formats and recognising traditional gender norms and socio-cultural beliefs and practices.

Additional efforts may also be needed for locally marginalised groups, such as women, children, elderly people, people with disabilities, and people from minority groups. Their involvement is critical to ensuring that prevention activities and other aspects of the response are effective for all.

Men are potentially more vulnerable to cholera than women and other locally marginalised groups. This may be due to their greater mobility, as well as more limited health seeking and interaction with health facilities which may result in their lesser access to good health information.

Surveillance with communities

Communities are often the first to identify cholera cases and report them to health actors. Community engagement can help build trust and strengthen rapid case identification and referral to treatment facilities. Effective communication between communities and formal responders can also supports the flow of other critical information, such as how interventions are perceived in the community and what kinds of information, including rumours, are circulating.

Community priorities beyond biomedical concerns

The Government of Zambia has banned gatherings at funerals of people who have died of cholera. This response may be disproportionate given the oral-faecal transmission of the disease. It may also risk people not reporting cholera deaths.

Funerals play a fundamental psychological, cultural and symbolic role for family members and communities. Modifying burial and funerary practices in conjunction with trusted individuals within the community, including faith leaders, is essential. Priorities should include hygiene measures at burial sites, such as access to safe water and hand-washing facilities; feasting practices following funerals; ensuring that families are fully informed of the whereabouts and condition of their loved ones, and what process is to be followed after their deaths.

Support community knowledge and capacities

Many communities have their own knowledge and coping mechanisms to deal with disease outbreaks, including cholera. In South Sudan and Sierra Leone for instance, communities initiated quarantining strategies, and changed eating, and dish and clothes washing practices, among other measures. In other settings, home-made oral rehydration salts and traditional medicine and prayer have been identified as important.

Community engagement efforts should aim to identify and support local strategies and practices, as well as draw on local capacities to support other measures, such as hiring trusted local people to work as contact tracers or in other aspects of response. Responders should also listen to concerns from the community about its lack of capacity or resources to dedicate to the cholera response, and support accordingly.

Structural barriers to community action

Risk communication is often one-way and focuses on providing information to people on how to prevent transmission, seek help, and care for others. Sharing and promoting the best available information must be underpinned by recognising the structural barriers that communities face in acting upon that information.

Responders should work with local understandings of cholera and train community volunteers and disease surveillance staff to use these understandings and the right language in their work.

Whilst it is important to work with local governance structures and health system actors, it is also vital to understand and carefully navigate power dynamics within and surrounding communities. Local elites, health workers, and military, police, and government leaders may not be trusted by communities and may limit their abilities to take actions. Responders need to identify locally trusted people and networks to work with, while recognising that these may not be obvious.

Strengthening community feedback mechanisms

Community feedback, including queries or complaints, is an important component of community engagement during a cholera response. Feedback data focuses on how community members perceive and experience the response and the cholera outbreak more broadly. Feedback supports accountability of response actors to the people they are serving and can be gathered through informal, proactive and passive processes appropriate to the local context, including the preferences of affected people.

Those coordinating community engagement and involvement locally should ensure that people providing feedback receive timely responses and follow-up when necessary and appropriate. Even if feedback is passively gathered, it must be proactively managed.

Risks and opportunities

Cholera outbreak preparedness and response strategies must be centred on the circumstances and needs of communities and the experiences and insights of local responders who often are part of these communities. Without this, strategies can be inappropriate, ineffective, intrusive or even harmful to communities they are supposed to be helping.

Meaningful community engagement and involvement can also enable the WHO, Member States and partners to draw lessons from the current and past outbreaks and make context guided adjustments to improve control cholera and the lives of people most affected.