Value for Money (VfM) has been a hot topic in the international development arena since it emerged in 2010, championed by the Department for International Development (DFID) as a mechanism to increase transparency around aid spending and promote stronger accountability to the tax paying public. Improving aid accountability is essential for the survival of the sector. But questions remain about how we meaningfully measure VfM, going beyond formulaic approaches and digging deeper into currently under-explored opportunities to develop more innovative and participatory approaches to VfM that improve downward, as well as upward, accountability and place greater emphasis on learning and adaptation.

INGOs and other development actors have spent significant resources to understand what VfM means in practice and how to make the best use of it. Nevertheless, there is still no common understanding of VfM across the development sector and increasingly more organisations are forced to outsource this piece of work without successfully addressing it and learning from it.

The Department for International Development (DFID) defines VfM as ‘maximising the impact of each pound spent to improve poor people’s lives’. This means that VfM offers organisations the opportunity to critically reflect on whether they are achieving the best possible change and the extent to which the resources are allocated in the right places. However, to date the VfM debate has placed much more emphasis on demonstrating the maximisation of each pound than the much harder to quantify improvements in people’s lives.

The conventional approach to VfM

Donor frameworks such as DFID’s 4Es framework have attempted to define VfM as a balance between economy, efficiency, effectiveness and equity (the 4Es). In practice, because economy and efficiency are easier to measure than effectiveness and equity, VfM has tended to focus too heavily on demonstrating savings and emphasising how goods and services have been procured. Something that was highlighted recently in the Independent Commission for Aid Impact’s (ICAI) ‘Review of DFID’s Approach to Value for Money’.

This approach to VfM does not sufficiently explore the concept of value in terms of what it actually means for people living in diverse religious, cultural, political or rural/urban communities. Value for whom? Value by when? Value of what? How disparate are understandings of the value of the work across very different communities?

Instead, the focus of VfM indicators is on monetary and/or quantitative metrics, such as cost per beneficiary or cost per output which are expected to enable funders or other actors to compare programmes, even when the contextual differences are so massive that comparisons are often inappropriate and not conducive to useful organisational learning.

ActionAid’s attempt to shift the VfM debate

From 2012-2017 ActionAid delivered a pilot project to develop its own understanding of VfM and explore methodologies to measure and analyse VfM that were more consistent with its values and its human-rights based programming. With the support of Daniel Buckles, a researcher grounded in the tradition of Participatory Action Research, ActionAid developed a participatory methodology to enable vulnerable women it works with in communities across the world to assess the VfM of its programmes.

The methodology was developed to ensure that:

1. Vulnerable women are at the centre of VfM analysis, reversing the VfM debate from an upward to a downward accountability exercise.

2. VfM analysis leads to adapting programmes so that they respond to what is valued in the communities where it works and to the extent to which resources are allocated in a way that enables change to happen.

3. VfM becomes part of the ways of working rather than requiring external outsourcing.

The methodology uses a set of tools inspired by the Outcome Harvesting evaluative approach to understand the significant, moderate and limited changes experienced by programme actors. These are then related to the investments in the different areas of work, taking into account financial, human and in-kind, to be able to discuss which investment are generating change and, if they are not, what needs to change for this to happen.

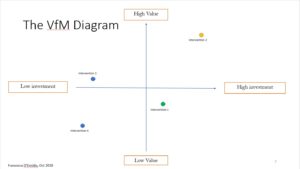

The findings are summarised in a VfM diagram where the different programme areas are distributed across four quadrants separated by two axes illustrating the value and the investment. This helps to visually represent the areas that are not VfM (bottom two quadrants) and those that are VfM (top two quadrants). The purpose of the exercise is to identify potential changes in the strategic approaches and/or the allocation of the resources that would enable all the programme areas to be placed in the top two quadrants and therefore be VfM.

A call for action

To date the definition of VfM and the 4Es framework have been taken as a blueprint which most organisations have adhered to without question. However the VfM agenda is also an opportunity to encourage organisations in the aid sector to really reflect upon the nature of their work and how their investments lead to lasting and meaningful change. VfM has significant potential to prompt open and inclusive conversations between development actors, partners, donors and the poor and marginalised groups to help build a stronger culture of organizational learning, evidence based decision making and adaptation to maximize impact in the sector.

ActionAid’s efforts to shift the VfM debate is an example of how organisations can engage with the VfM agenda to develop mechanisms to listen and learn, gather feedback and analysis from the individuals most affected, and jointly review and assess the value of the work in order to adapt programmes to improve impact. People who are experiencing programmes are often in the best position to assess what is working and what is not and what may be done differently to enable change to happen, and as a sector more needs to be done to acknowledge their right and capacity to draw their own VfM conclusions and to bring these voices and different perceptions of value into the conversation.

Francesca D’Emidio is an MEL Consultant supporting INGOs to develop VfM frameworks and is an Associate Trainer for BOND on ‘Putting Value for Money into Practice’.

The Knowledge Impact and Policy team (KIP) cross cuts IDS. It has 16 team members and 14 affiliate members with a range of thematic knowledge, MEL and communications experience. To make the most of our collective genius and to make space to learn from each other, KIP convene regular internal discussions aimed to broaden our thinking.