My work with the Centre for Development Impact is to help the evaluation of development impact. This implies research to detect outcomes that change in response to a project or a programme, and explore for the conditions that contributed to the realisation of these effects. However, these projects and programmes are always context-dependent. Each impact study, or for this blog post, ‘effectiveness’ study, has specific characteristics that make their impact ‘unique’, which limits the usefulness of their findings to the outside world – the so-called ‘external validity’.

Why do we talk about ‘external validity’?

This heterogeneity in contexts, type of development support and quality of implementation makes it complicated to draw overall conclusions from impact studies. Nevertheless, it is essential to draw more generalised inferences. Or, quoting Bates & Glennerster from a recent article on the external validity of J-Pal Randomised Controlled Trials, ‘Having evidence from specific studies is fine and good, but for policymakers, the point is not simply to understand poverty, but to eliminate it’. What the development practitioners and politicians are interested in is what has worked elsewhere, so they can draw on that when designing new programmes.

The discussion on external validity is not new and will remain a point of discussion. For example, in 2013, Sandefor and Pritchett emphasize that an intervention may have effects that depend more on context than on personal/household characteristics, and are particularly critical of the use meta-analysis as a way to gain more confidence in an intervention’s effectiveness.

And, I need to admit that they are right. Together with colleagues in Wageningen and Ghent, I recently finished a systematic review of the effectiveness studies that assessed the income effects of contract farming for smallholders. It has been a quite challenging endeavour. Not only because of the time-consuming process of electronic searching and subsequent filtering out of studies – for which I learned recently, in a Centre of Excellence for Development, Impact and Learning (CEDIL) event in London, that some technical options exist to reduce the burden, but, especially, because of this challenge, described above, to draw overall conclusions from a set of locally-embedded studies.

The systematic review was commissioned by 3ie, and, following the strict Campbell Collaboration reporting requirements, meta-analysis of the effect sizes was mandatory. Our initial proposal to do a more qualitative ‘realist synthesis’ became budget-wise impossible under this assignment, though we tried to pull out some learning about enabling configurations of conditions, using Qualitative Comparative Analysis.

The challenges of a ‘contract farming’ meta-analysis

Though our review was specifically about the ‘income effects of contract farming for smallholders’, this was quite a complex question. Contract farming is a sales arrangement agreed before production begins, which provides the farmer with resources or services. The service package provided by the firm varies per location, and can include transport, certification, input provisioning and credit. In impact evaluation jargon, this implies a huge diversity in treatments, treatment conditions, and implementation modalities. For example, one study might analyse contract farming in vegetables, another in coffee. One contract farming arrangement might include credit, another only technical support. One contract is negotiated between a firm and a cooperative, another is offered as a take-it-or-leave-it to individual producers. A huge range of different support packages provided to the farmers!

For the meta-analysis, we only included studies that examined the impact of contract farming on income and food security of smallholder farmers in low- and middle-income countries. Studies had to use a comparison group with appropriate statistical methods to allow for selection effects. We identified 75 studies of those, and 22 studies were of sufficient rigour to include in the meta-analysis of income effects.

The limited number of studies do not cover the whole range of sectors in which contract farming is an important way of procurement (e.g. sugar, dairy, barley, banana, asparagus, fresh fruit). Nor do they cover the entire palette of analytical methods used in the social sciences. Moreover, the set of studies showed a marked publication bias; all included studies report on at least one case of contract farming that has a positive and statistical significant income effect. This suggests that studies that find no effects or negative effects are likely to be ‘buried’ and not worked out by the authors into an academic publication.

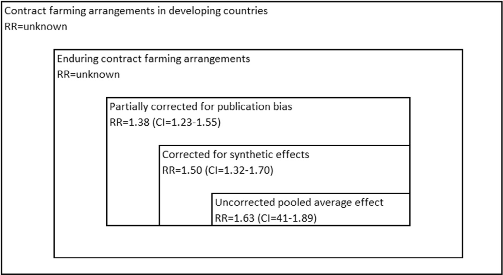

We used some econometric tricks to partly correct bias. However, even with this partial correction, we are sure that the average income effects are upward-biased, because of survival bias. All studies used a data from surveys some years after the contract farming arrangement started. In practice, many contract farming arrangements will collapse in these initial years, when trust between the firm and the farmer needs to be build and services and contract conditions need to be refined. Because these failed attempts are left unstudied, the average effect gives a too bright picture of contract farming as a pathway of development.

What did we conclude?

We summarised the (known and unknown) average effect estimates in a figure in an upcoming publication in World Development. The figure below illustrates the limits to estimate of the pooled average effect-size. The meta-analysis of the 22 studies showed that, on average, the contract farming had improved incomes of farmers in the range of 23 to 55 per cent. It remains however unknown what the average effects would be when we had a broader, more representative set of studies, and when we would have the possibility to include also the contract farming arrangements that failed in their initial years.

Yet, publication and survivor bias may well apply to the wider literature on the impact of development interventions. As long as these biases are not properly addressed, systematic reviews and research evidence-gap maps may only provide a partial and biased view of the real effects of development support.

Notwithstanding the limitations, our key findings, or our cautious ‘generalised causal inferences’ are:

- Contract farming may substantially increase farmer income. Overall, the studies show effects that lie in the confidence interval of 23 to 55 percent

- For farmers to give up their autonomy in marketing and prevent side selling, substantial income gains need to be offered

- Price premiums on farm products are often needed as part of the service package provided by the firm to do so

- Poorer farmers are not usually part of contract farming schemes. Contract farming is more suited to the relatively better-off segment of the farming population that are able to take more risks.

And, yes! when a funder would accept a more in-depth ‘realist synthesis’ of the contract farming literature, I would love to do so. I expect that more (qualitative) insights can be drawn from the literature than we did in the current analysis. However, also realist synthesis will face threats to validity and result in contestable causal inferences. It is good to get used to these boundaries of the so-called ‘generalisation domain’, as these limits to external validity are inherent to the way that we have to make sense of a complex reality.