In the third and final blog sharing findings from a survey of attitudes towards the Hazara Shia in Quetta, Pakistan (following government broadcast messages referring to ‘the Shia virus’), Mohammad Aman and Sadiqa Sultan compare and contrast the responses of men and women and postulate what factors may lie behind them.

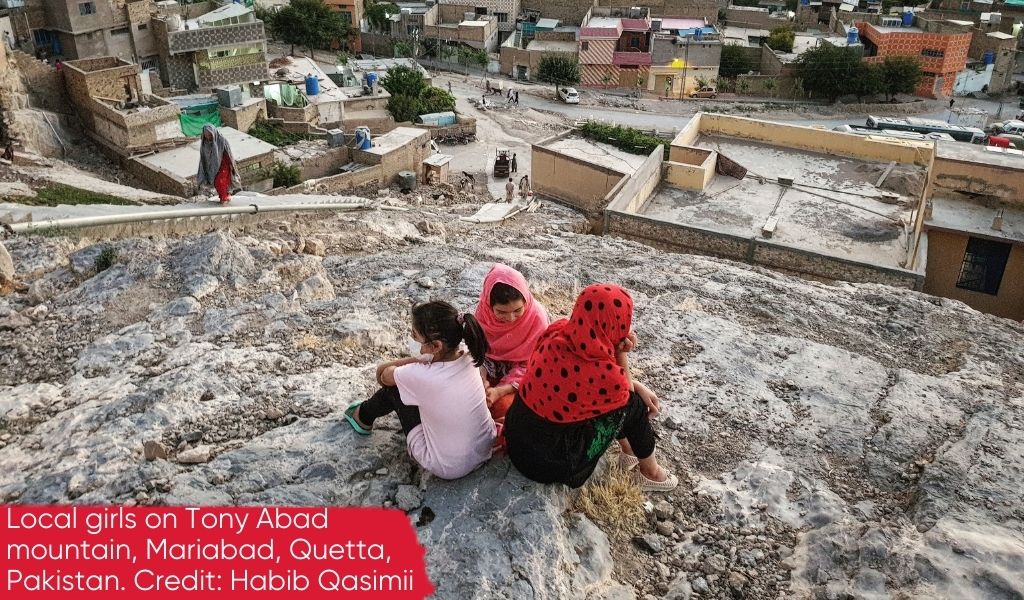

Local girls on Tony Abad Mountain, Mariabad Quetta, Pakistan. Credit: Habib Qasimii

Local girls on Tony Abad Mountain, Mariabad Quetta, Pakistan. Credit: Habib Qasimii

While the Covid-19 pandemic has affected all communities around the world, minority communities have evidently been hit hard. Described by UN Secretary-General, Antonio Guterres as “a tsunami of hate and xenophobia, scapegoating and scare-mongering”. Examples include Asian and Asian-origin communities around the world, especially the Chinese, experiencing racist violence and discrimination, Muslims in India being made scapegoats for the spread of coronavirus, while in Pakistan, the gravity and extent of discrimination against the Hazara Shia community in the wake of the Covid-19 outbreak had never been seen there before, even given the fact that Hazara Shia have already suffered over twenty years of escalating violence and targeting.

These episodes of prejudice started with the blaming of Hazara Shia pilgrims returning from Iran for the outbreak by key officials of the Balochistan Government. This was followed by unparalleled biased attitudes and interventions by the authorities such as sending Hazara personnel in government offices on forced leave without even testing them for the virus, denial of access to health services to the Hazara population, and inhumane treatment of pilgrims around the border areas upon their return. They also bore losses in their businesses and were forced to put up with greater restricted movements in the city and province than non-Hazaras.

A team of researchers based in Quetta conducted survey, with support from the IDS-led Coalition for Religious Equality and Inclusive Development, to explore the views of non-Hazara and non-Shia populace of Quetta city regarding the coronavirus, government response, and Hazara Shia pilgrims and the outbreak. A comparative analysis of the responses of men and women yielded interesting findings.

Women’s attitudes towards Covid-19 and the government’s attempts to control its spread

One striking finding from the survey was that, when asked if coronavirus was a scientific fact or a conspiracy, 68% of female respondents, compared to 48% of male respondents, contrary to evidence which shows that, in Pakistan, women tend to hold more superstitious beliefs than men (PDF).

In the aftermath of the outbreak, a general distrust was seen globally towards governments and health practitioners and Pakistan was no exception. The survey revealed that the majority of women surveyed (56%) were not satisfied with the measures and management by the government to fight the virus, but they appeared on the whole a lot more tolerant than their male counterparts as 84% of men surveyed said they were not satisfied by the measures taken.

Similarly, when asked if they would be comfortable if a quarantine centre was to be established in their neighbourhood, women tended to be more flexible and raised fewer concerns compared to men (47% to 33 % respectively). When it came to following the WHO Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) to help prevent Covid-19 transmission, such as wearing a mask and social distancing, women did a lot better than men. A significant majority (79% ) of women surveyed said they followed the SOPs all the time compared to 54% of men. In the context of Quetta, which is an interesting mixture of semi-urban and semi-tribal cultures, women’s roles are more centred around the home and therefore they have less mobility than men. This could be one reason why women said they were more successful in maintaining social distancing.

Contrary to the trends in the responses discussed above, however, when it came to singling out Shia pilgrims for the spread of coronavirus in Balochistan, women do not extend solidarity to this religious minority any more than men: 44% of female respondents said the pilgrims were the main reason for the virus spread compared to 37% of men.

So, what explains the responses and attitudes of these women?

The sample population for our survey constituted men and women from all major non-Hazara ethnic communities in Quetta. Most of the women approached educated, to at least 12 to 14 years, which will have helped them gain a reasonable understanding and approach to the virus and its transmission. Women’s tend to provide more support and deal better with difficult situation than men, according to recent research, and this tendency may have played well into their following the SOPs to protect their loved ones.

But when it comes to the political and social aspects of the pandemic, women seem to rely on already-prevailing narratives (blaming Shia Hazara for the outbreak) because they have not been included in the political and social discussions either at home or at the institutional level. This could be why more women (44%) believed the government narrative that explicitly blamed Hazara Shia pilgrims for the outbreak.

Men, on the other hand, were influenced by different facts (for example, the media, peers, interactions with other communities etc.), and, as a result, they were more open to a spectrum of views. Some equally rejected/scapegoated the minority, others felt unsure one way or the other, still others actively criticized the state narrative of blaming Hazaras. All the same, more than one third of respondents were likely to ultimately accept what the government told them.

Given the patriarchal and semi-tribal prevailing norms of men controlling all important matters in individual and collective lives in Balochistani society, men have traditionally been more visible and active in showing prejudice towards minorities for example, through online and offline hate speech and inciting violence against Shia Hazara. So, their blaming of the minority did not come as a surprise in the survey. But it was interesting to see this apparent bias in women too. It was saddening to see that women who are themselves victims of patriarchy, poor governance and discrimination on a daily basis, could not relate to, and empathise with, the situation of Hazara Shias. This could be a worrying omen for a less tolerant Balochistan in the long run.

Muhammad Aman is an educationist based in Quetta, Pakistan. He tweets at @amn_o_aman.

Sadiqa Sultan is a Research and Development Consultant. Her work focuses on different aspects of peacebuilding. She is a graduate of the University of Otago, New Zealand with a Master’s degree in Peace and Conflict Studies. Follow Sadiqa on Twitter.