This is the second blog in our reflective series. In our first blog we introduced the Full Spectrum Coalition (FSC) evidence and learning group, the challenge it responds to and the need to move beyond the performative dance that gets in the way of meaningful evaluation design. Here, we reflect on deliberation during a one-week in-person design workshop hosted by Tostan in Senegal, offering a peek into the world of messy evaluation design.

Our goal for the workshop was to use a carefully facilitated deliberative space, such that we – representatives of each of the five partners (Tostan, Legado, One Village, IDS and IDinsight) – would articulate a common research agenda grounded in shared values and ethics, encompassing respect, dignity, inclusion, and equity, that recognise the vital strengths of communities and their role as agents of their own development. This was a first step in bringing the joint evidence and learning agenda to life, a small movement towards realising its potential to support Holistic Community-led Development (HCLD) becoming more fully refined, resourced, and recognised as a leading strategy for sustainable wellbeing.

The design process

We began by mapping out the high-level theory of change of the common approach to HCLD across all partners. We noted where there is already a substantial body of evidence about parts of the approach for some organisations and in some programming contexts (e.g. Breakthrough Generation Evaluation for Tostan). This includes past evaluations conceptually grounded in key theories (self-efficacy, social norms, etc.), as well as evidence produced by adjacent initiatives (e.g. Rapid Realist Review on Community-Led Development). What is unique for this joint endeavour, is that we are studying a common approach to understand its value beyond individual organisational operationalisation.

To identify our evaluation questions, we discussed outcome areas common to all partners about ‘social transformation’ (e.g. capacity to aspire, social cohesion, change in social norms, including toward more equitable gender norms and more decrease in violence), ‘governance’ (e.g. the existence of a legacy plan or shared vision, the presence of inclusive decision-making processes) and ‘human development’ (e.g. economic wellbeing, health, education). We also noted some distinct outcome of each partner e.g. the Legado programme includes community-led, site-specific environmental outcomes; One Village Partners include gender equity as a core pillar; and Tostan has worked for many years with a focus on social norms.

Based on this agreement, the collective high-level theory of change, through small group discussions, we identified an overarching research objective:

“to understand if, how and for whom the common approach to HCLD contributes to social transformation, governance and human development outcomes, how these in turn support sustainability and scale, and the role of power in mediating them.”

This places emphasis on the transformative role of the approach itself – the ‘how’ – pointing to the need to consider the changes in social relations, including how they are mediated by power dynamics. It also requires evidencing causal relationships if outcomes are achieved – the ‘what’. Building an appropriate design, therefore, required deliberation between, and crafting a bricolage of, multiple methodologies.

We agreed that a theory-based approach can help to zoom in and articulate detailed causal pathways to be explored through, for example, realist evaluation, among other potential methodologies – adhering to the rule that methods are appropriate for the specific causal dynamics being investigated. Through this work, we can refine, build, and contextualise theory about the specific mechanisms the HCLD approach fosters in individuals, households and communities under different conditions, ensuring our evidence is transferable to other contexts.

Recognising the need to measure the presence (or lack) of outcomes (to support theoretical explanation), we then had to deliberate design options to provide quantitative measures of change. An earlier evaluability assessment conducted by IDinsight focused on the Tostan Community Empowerment Program had already ruled out the possibility of using a randomised control trial, given Tostan’s careful village selection process. The need for contextualisation and flexibility, and the organised diffusion component of the intervention design that means it is difficult to avoid ‘spillover effects’, also posed a design challenge.

Instead, the IDinsight team proposed a quasi-experimental design using matching, which requires a large sample size (70 – 100 villages for each of the ‘treatment arms’). Operationally, this felt like a tall ask for organisations that tend to work with cohorts of villages that usually do not surpass 50. Further, ethical dilemmas about using control sites were voiced by some team members, given the extreme levels of poverty in all potential new intervention sites.

Deliberating on multiple forms of appropriateness

Distinct positions on whether to use a counterfactual design or not shouldn’t be surprising. What was unusual in this experience was the ability to safely surface what often remains hidden – that we (evaluators, researchers and implementers) all come into design conversations with already formed and often very strong views (biases) on what types of comparisons and counterfactual designs are ‘appropriate’ that stem from a mix of our individual, disciplinary, organisational, axiological and epistemological positions. Ensuring we did not collectively fall back into simple views and rehearsing of long-standing debates about ‘gold standard’ designs as better required careful deliberation. One exercise was crucial to finding a way through the potential impasse.

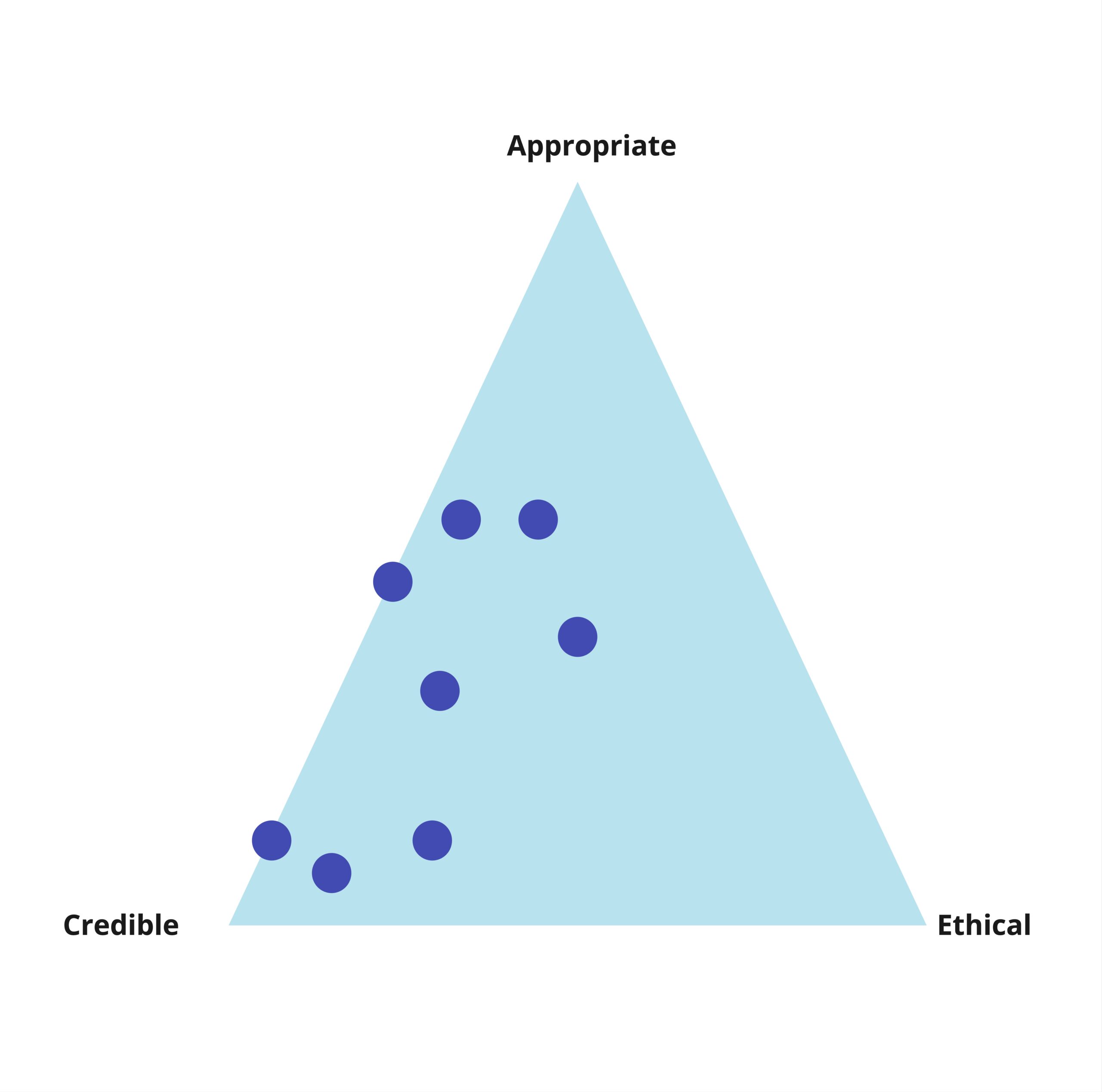

Using the criteria of credibility, appropriateness and ethics, we each plotted our view of how important a counterfactual design (to sit within the theory based approach we had already agreed on) would be to: (i) credibility of the findings; (ii) appropriateness of the design; and (iii) upholding ethical standards aligned with the values of the FSC and the HCLD approach (shown in Figure 1).

This exercise brought into the open our distinct positions. One team member placed their dot in the middle, taking the position that a counterfactual design is equally (and highly), credible, appropriate and ethical. All other dots were placed further away from the ethical corner, suggesting that counterfactuals were viewed by most others as less ethical than other design options that do not require comparison sites. There was broad agreement that our audiences would find evidence resulting from the inclusion of a counterfactual design credible and this was an important reason to consider it (with two of the dots suggesting it was credible but not appropriate nor ethical). On the other hand, a few felt it would be appropriate and support credibility.

Visualising and reflecting on our positions allowed us to connect across our plural and nuanced perspectives, because as individuals and organisations we are not monoliths. We are users of evidence who are also implementers of programmes; researchers who are also facilitators of learning embedded in participatory programmes; independent evaluators who uphold scientific views of rigour while also being client driven and valuing ethics. There is no simple ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answer to these difficult choices. Through this experience we have come to share a belief that for knowledge to be useful it must be credible, and for our team, being values-aligned is critical to our joint endeavour.

You might wonder if we landed on a ‘middle ground’ solution that compromises critical positions, or if we came to an agreement that allows all in the room to feel their views are reflected in the shared endeavour? You may also wonder how we manage the reality that community members, those at the heart of HLCD, were not in the room at all?

We continue to deliberate our design checking operational viability with teams in the field and aligning our goals with the lived realities and interests of communities. We will share updates, but in the meantime, find out more about how to join our initiative.