Climate change is causing shifts in rainfall patterns across the world, damaging agriculture and livelihoods and impacting millions of lives globally. In India, farmers in rural Gujarat are caught in a cycle of droughts and floods, and increasingly frame the impacts of these co-located hazards in the form of ‘leelo dukaal’ (green drought).

Researchers from the ANTICIPATE project attempt to unpack this phenomenon by bringing together scientific understandings and local experiences. They argue that while much of the attention remains on episodes of ‘extremes’, it is the slow onset or creeping hazards that need our attention.

For the last two years, our research team has been exploring how local communities in Banaskantha (North Gujarat) experience and cope with the extremes of drought and floods, which have become more frequent in the past decade. While exploring the lived experiences and impacts of these hydrological extremes, we were struck by the framing of ‘leelo dukaal’ (translated into English as ‘green drought’). This was reported to us as the fall out of an untimely and ‘strange’ pattern of monsoon rains (July to September), which were leading to water-inundated farms and crop devastation.

Although the Indian monsoons play a vital role in sustaining agriculture, and ensuring food security, the timing and quantity of the rainfall has always been a matter of great trepidation for farmers. In recent years, farmers in Gujarat have reported increased episodes of flooding and waterlogging, which causes the loss of standing crops in the short term, and soil erosion and depletion of soil quality in the long term.

Our research has found that local communities are struggling to cope with the intersecting impacts of drought and floods. With the shifts in traditional seasonal weather patterns, many regions in this state are now experiencing intense heat and drought from May to July, followed by extreme rainfall and floods from August to September. We have described these spatial and temporal overlaps as co-located hazards in our research.

Droughts in Banaskantha, Gujarat-a historical overview

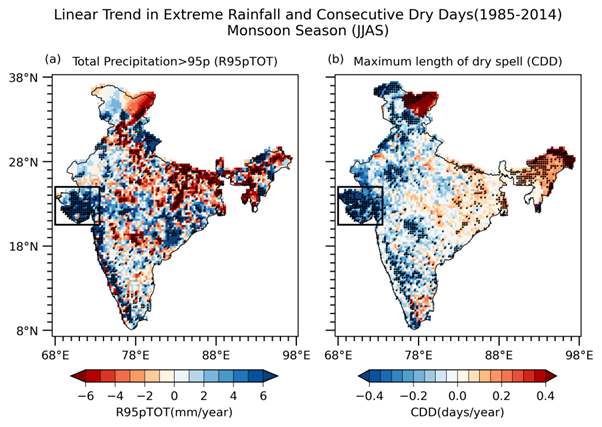

The state of Gujarat falls under the arid to semi-arid regions of Northwest India. The year 2019 saw one of the most devastating droughts in the state whereby Gujarat only received 196 mm of rain between January and July, which is just a fraction of its usual 816 mm (down 86 percent) and rainfall in Banaskantha was 81 percent down in the same period. Climatologically, India experiences the highest levels of heavy rainfall along the west coast, but recent observations (1985-2014) indicate an increase in extreme rainfall as demonstrated by Figure 1 below.

Drought was officially declared in Banaskantha in 2012-13, 2015-16, and 2018-19. Irrespective of whether the government has declared the district as drought affected, the district has experienced significant monsoon deficits over the year, the impacts of which are further compounded due to a lack of drought relief measures and compensation, exposing communities to greater shocks when hazards such as floods strike.

Unpacking ‘green’ drought

Amidst the different classifications of drought, such as meteorological or hydrological drought, green droughts are a deceptive scenario where vegetation appears lush and green despite underlying water stress at the roots. Green droughts are characterised by stunted plant growth and reduced crop yields, making them challenging to detect and diagnose. Contributing factors include uneven rainfall patterns, high temperatures, shallow-rooted plants, and soil compaction, which hinders water reaching down to the root zone. At the outset, this description fits well with the local experiences of green drought in Gujarat. However, as critical studies on drought and water scarcity tell us, the impacts are experienced differently depending on social difference and markers of vulnerability

Lived experiences of ‘green drought’ and its intersectional impacts

In rural Banaskantha, memories of the 1986-87 drought are often invoked, where people speak of a dukaal (hard time) where there was “no water, no food to eat and the pervasive loss of livestock”. Green drought, however, presents a contrasting situation where dukaal is triggered not by water scarcity but by the abundance of water. There is green cover in the field with weeds and grass but limited to no crops left to harvest. As with slow onset events, the impacts of green drought also evolve over a longer period, leading to slow depletion livelihoods.

Differential impact of green drought

According to farmers in our field site, leelo dukaal affects all stages of cultivation. Continuous rains during the initial monsoon saturate the soil, delaying or preventing the sowing of crops (cotton, castor, fodder and pearl millet). Even if crops are sown on time, continuous rains hinder growth, causing waterlogging and crop stunting. For example, during the 2022 monsoon period, the impacts ranged from total crop failure in cotton crops to reduced harvests and poor crop yields in castor. This loss not only impacted household food security but caused economic instability for a full year and causing vulnerable households whose farms were damaged to migrate from the village.

Soil type determines the impact

Several farmers mentioned that the effects of leelo dukaal differ based on the soil’s ability to absorb or drain water. The majority of the farms in the village range from sandy, to sandy loam soil. According to farmers and an agriculture expert, although sandy soil absorbs water more readily, crop failure is more common in sandy soil. It is good for bajra/pearl millet but not for the profit-generating cotton and castor crops. Even in a successful season, the weight of the harvested crop from sandy soil is lower than that from sandy loam. Yet, crops grown in sandy soil tend to be more resilient during daily rainfall compared to sandy loam. This means that farmers with predominantly sandy loam soil face the brunt of damage. The situation, however, remains dire for sharecroppers and landless labourers where loss of one season can be catastrophic since they have limited resilience to shocks and stressors.

Increased workload for women

As cycles of sowing and loss continue within the monsoon season, the majority of labour falls on women. They not only face difficulties in carrying out household chores, which include walking long distances for good quality water but are also tasked with additional responsibilities of collecting fodder when crops fail. The monsoon season sees women working the longest hours of the day. With farm emergencies (such as undertaking multiple rounds of sowing during the same season, extensive weeding of vegetation and assorting of failed harvested crops) this increase in workload remains unrecognised and unpaid.

Way forward

In these parts of the country, green drought is a new phenomenon, and its impacts are slowly emerging and becoming visible as wet days intensify in the region. For example, in 2024, Gujarat has experienced widespread flooding and heavy rainfall during the monsoon period. More investigation is needed to understand this phenomenon as both a social, ecological and hydrological condition. Understanding these increases in extreme rainfall and dry spell patterns is crucial for developing adaptive strategies to mitigate the impacts of climate variability on agriculture and water resources, in Gujarat and beyond.