This academic year, students from our master’s programmes organised a weekly Anti-Caste Reading Circle. MA Gender and Development student Chandni Sai Ganesh writes about her experiences of enriching her learning outside the classroom through the student-run initiative.

One of the first readings we were assigned as part of our curriculum this year was Dr Farhana Sultana’s essay on decolonising development. This made me think about the material basis of “decolonising” in the context of South Asia. What does it mean to decolonise development in a country like India, for example, where privileged caste hegemony determines human development? Curious to find answers, a group of students and I formed the Anti-Caste Reading Circle. It quickly became a brave space for discussion and learning.

Why does caste matter?

Caste is a system of hierarchical social stratification prevalent across South Asia and characterised by hereditary social groups, endogamy, and social barriers. It continues to shape the socioeconomic contours of countries such as India, Pakistan, and Nepal, among others.

In India, where I am from, caste is a strong indicator of crucial aspects of human development. For instance, the life expectancy of privileged caste Hindus in India is three years higher relative to marginalised Dalit castes. Furthermore, privileged caste Indians are twice as likely to enter higher education as their oppressed caste and Adivasi (Indigenous) counterparts . And, approximately 55 per cent of India’s national wealth is held by its coterie of privileged castes, although we comprise a significantly smaller proportion of its population.

While the nation has made some progress towards tackling caste inequality, the system continues to dominate public and private life. Affirmative action policies are constantly under threat. For example, Dalit, Adivasi, and allied groups organised a nationwide strike on 21 August, 2024 in response to the Supreme Court’s decision to permit the sub-classification of Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes, widely seen as an attempt to weaken affirmative action.

The Anti-Caste Reading Circle becomes a brave space for discussion

These socio-political realities have a significant impact on India’s development. When the country’s development story, one we share with our neighbours, is constructed and narrated by an elite few, I am compelled to ask: Whose reality counts?

This is why I was motivated to start the Anti-Caste Reading Circle. I believe the chokehold caste has on development in South Asia cannot be separated from the curriculums or programme interventions we design. IDS has worked extensively across India and South Asia at large; as part of my master’s course in Gender and Development, I was incredibly privileged to learn directly from teacher-practitioners like Lyla Mehta (whose research Towards Brown Gold unearths caste discrimination in sanitation) and the Sustaining Power (SuPWR) team, which examines women’s power struggles in South Asia. However, I wanted to dive deeper into addressing caste inequities, taking an expressly anti-caste approach.

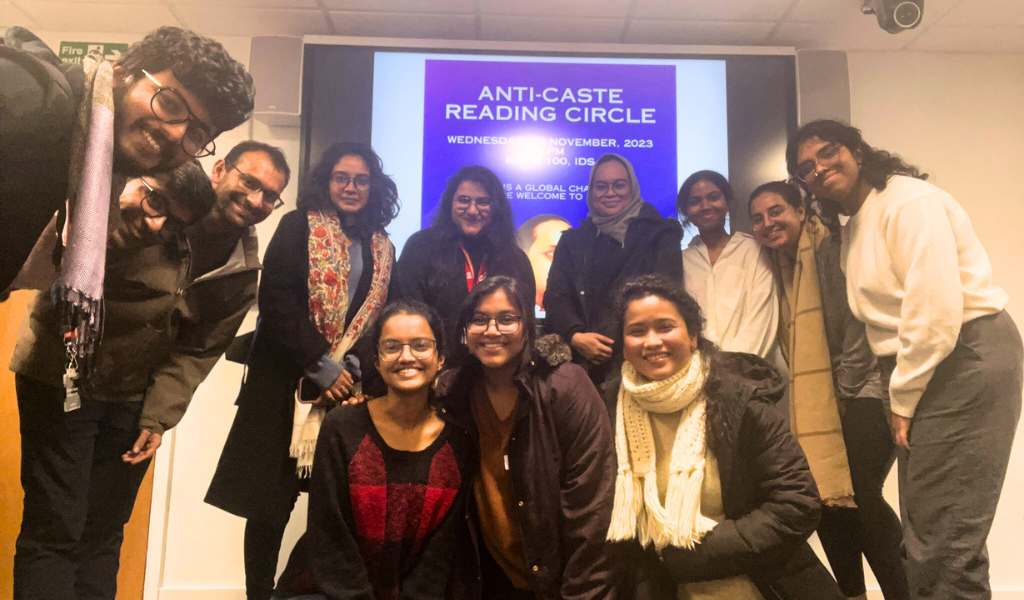

Therefore, seeking a brave space for critical thinking and thoughtful discussion, and a community of interlocutors equally committed to annihilating caste, I invited students and faculty at IDS and the University of Sussex (UoS) to read anti-caste literature with me. Together, as anti-caste leader Dr BR Ambedkar pioneered, we set out to educate, agitate, and organise!

Building community

Throughout the Autumn and Spring Terms, the Circle met weekly. We read excerpts of articles, watched videos, or had the privilege of listening to guest speakers who kindly agreed to spend a few hours with keen students. We heard from IDS Research Fellows who elaborated on caste in Pakistan and Pakistan-administered Kashmir. Additionally, we listened to a lecture on caste and labour markets in rural Tamil Nadu, India by Dr Geert De Neve, Head of Global Studies at UoS. Vinayak Krishnan, a PhD student, organised the talk. He stated, “We had an insightful discussion on how caste permeates garment factories in South India and the role of civil society in combating this.”

Dr De Neve was joined by Bethahemi Joy Syiem, Senior Partnerships Associate at Good Business Lab, who delivered a presentation on Indigenous land tenure systems and coal mining. Some of our other fantastic external speakers included Harshul Singh, Researcher at SOAS, and Susmit Panzade, Researcher at IIT Bombay, who joined us for a session on caste and queer identity. Panzade said, “The session opened portals for me in a way I could hear myself talk about my work and passions; I think it is enough for a researcher to feel validated when hearing your voice resonate with a kind audience. It was overall a very engaging experience.” Dr Dhaneswar Bhoi, Honorary Fellow at the University of Edinburgh, shared insights from his book, Caste and Everyday Life: Experience and Affect in Indian Society.

Additionally, the UoS Students’ Union (USSU) supported our efforts. During the USSU’s One World Week, we received funding to screen the documentary Chaityabhumi and hold a discussion with filmmaker Somnath Waghmare. He answered our questions and highlighted the importance of documenting Dalit movements in India. We also participated in the USSU’s 16 Days of Activism, through which we discussed the intersections between gender and caste violence. Lastly, we organised an interactive workshop about caste on higher education campuses in the United Kingdom with the USSU’s Culture and Liberation Community.

Student feedback

Shiyona Ann Gijo, a student pursuing an MA in Development Studies at IDS, reflected, “The group has been an extended learning circle at IDS. The conversations within the Circle have been a great learning and sharing opportunity. There is always something new and important we learn, especially about how caste interplays in an international setting. The Circle added a lot to my IDS academic experience.”

Simin Dharitree, a Chevening scholar pursuing an MA in Gender and Development, concurred. She stated, “Our classroom learning can become very specific, but this was a space where I could engage with a lot of literature and ideas about caste. It made me think deeply about myself, my surroundings, and how caste manifests across South Asia. I appreciated how a diverse group of students could share their stories. Some stories were eye-openers! Ultimately, the Circle added immense value to my master’s.”

The Circle came to life because of the support from IDS and UoS. The IDS Teaching Office was always helpful when we needed to book a room; lecturers and staff gave us advice on how to fund our initiative and some even attended our weekly sessions!

Top tips for new students

Starting your own initiative allows you to continue your learning outside the classroom. If this is something you are considering, here are my takeaways:

1. Stay curious: Is there a reading or a piece of research that sparks your curiosity? Follow that light. For me, that was all the literature I stumbled upon while researching for our weekly sessions.

2. Find your people: Talking about caste in a development context is not always easy. Identifying my friends and co-conspirators was key. Spend some time getting to know your peers and their interests. Work collaboratively.

3. Do not underestimate your reach: Drop that LinkedIn message or send that cold email. It can be daunting, but you will be pleasantly surprised by how many folks are keen on speaking to IDS students.