In my second blog on the findings of new research on knowledge translation (KT) in the global South, I want to focus on the implications of our findings for political science and development studies research agendas.

A fragmented field of study

Interest in the theory and practice of research engagement and research use goes back several decades. Although much related scholarship sits within the health sciences, it has roots in the sociology of science, science and technology studies, and social and political theories relating to the production and use of knowledge. In fact, it’s important feature across disciplines, sectors and geographies.

However, Southern perspectives are poorly represented in the somewhat fragmented academic literature. This is despite longstanding African, Asian and Latin American scholarship in sectors such as agriculture and health, on cognitive justice, indigenous knowledges and the politics of knowledge.

Research opportunities on knowledge production and translation

A research agenda exists that will produce both conceptual learning and actionable recommendations, but it requires further investment. We need to look beyond merely generating case studies or evaluating specific programmes and consider what learning can be shared between sectors and across regions.

This research needs to be shaped by researchers and practitioners who are familiar with specific socio-political contexts on the one hand, while donors and global institutions must create spaces for mutual knowledge exchange that transcend disciplines, geographies and sectors, on the other. The research questions relate to gender and social inclusion in producing and using knowledge, challenging knowledge hierarchies, and conducting political economy analysis of KT within a broader context of global and local challenges. These may include food systems, governance, fiscal policy, health, education and social policy.

A new analytical framework for understanding knowledge translation

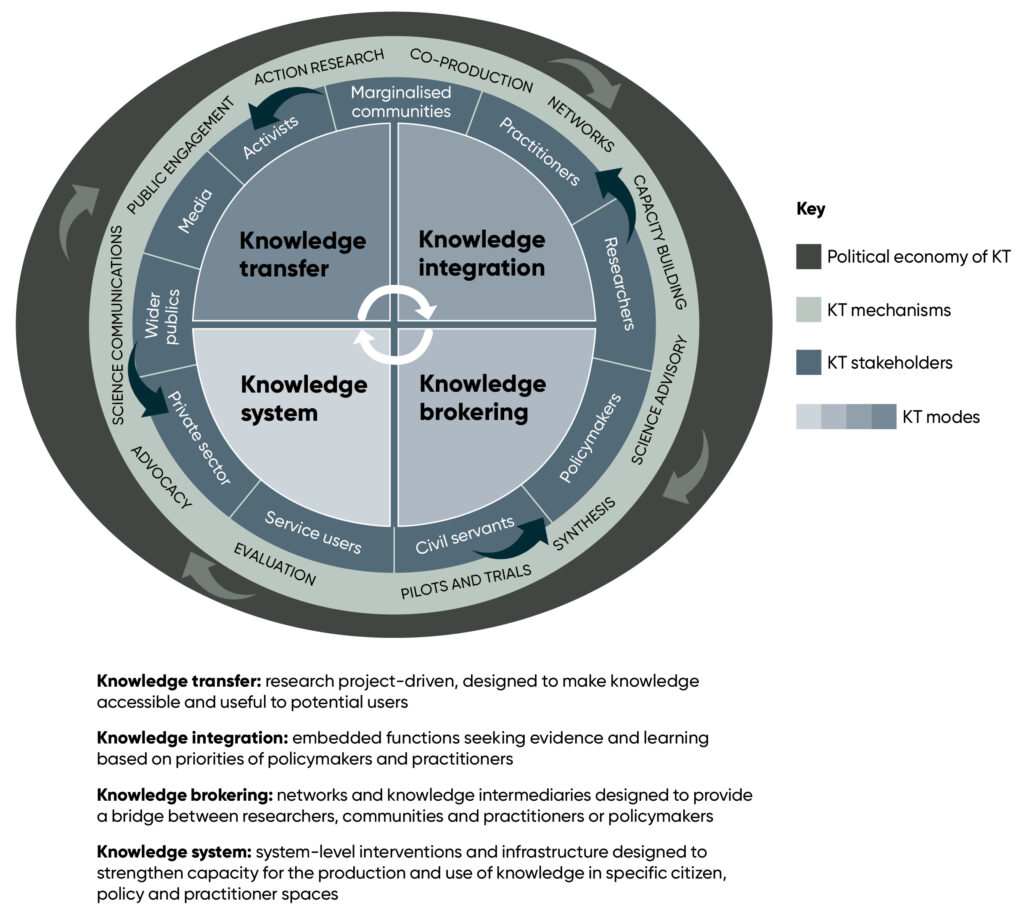

Over the course of our research, we developed and then reformulated our conceptual framework as evidence emerged around the production and use of knowledge. We dispensed with our original spectrum of increasingly interactive modes of KT and replaced it with an interlocking wheel of KT (see diagram below).

This allows an investigator to explore what combination of KT tools, stakeholders and causal processes best describe their experience, and use this to identify and test their assumptions about how change happens. It builds on our observation that in the global South the common denominator across all dimensions and understandings of KT is the explicit or implicit desire to bridge different ways of knowing.

This framework can be used to explore KT without relying on preconceived ideas about what it is, who does it and for whom. Instead, it helps identify a combination of outputs and stakeholders, then seeks to identify how these relate to the political economy of evidence production and use across specific contexts (outer ring). This might relate to power dynamics, political contestation, resources, excluded groups or donor agendas.

The inner ring prompts us to consider what assumptions are being made about causal processes and how research evidence interacts across these channels and stakeholders, given contextual factors.

Looking beyond co-production to focus on the use of research

What struck me about this was the need to encourage researchers and research funders to stop getting stuck on studying knowledge production and failing to also focus on knowledge use.

The current global trend around the benefits of more equitable research partnerships and the co-production of research is admirable but inadequate.

For research funders and institutions, discussions and action plans on equitable knowledge production have become common place. However, by making it all about research methods, research funding and research partnerships, are we in danger of ignoring an even deeper set of issues around research use?

These relate to the gaps in the literature we reviewed around how evidence shapes practitioners’ behaviours. There is very little up-to-date policy research on the impact of more inclusive research methodologies on policy formulation and implementation.

In the case study research (undertaken and published by OTT), you find lots of examples of how engaged scholarship produces more epistemically robust research that achieves high levels of engagement.

Nonetheless, it is far more difficult to identify how this relates to research directly or indirectly informing a change of direction in policy or practice.

What next?

Our study demonstrates that an empirical focus on use requires hyper local knowledge and embeddedness in political contexts. This is usually only accessible to national and local researchers, intermediaries and practitioners. Therefore, the natural next step from this research on KT in the global South, which touches on both production and use, would be to invest in a thorough exploration of research use in development. This will require collaborations that cut across sectors and geographies and are anchored in policy and practice communities.

The exploratory literature review we undertook contains the full results, including a structured bibliography and mapping of the state of knowledge on KT in the global South to support further study in this field.