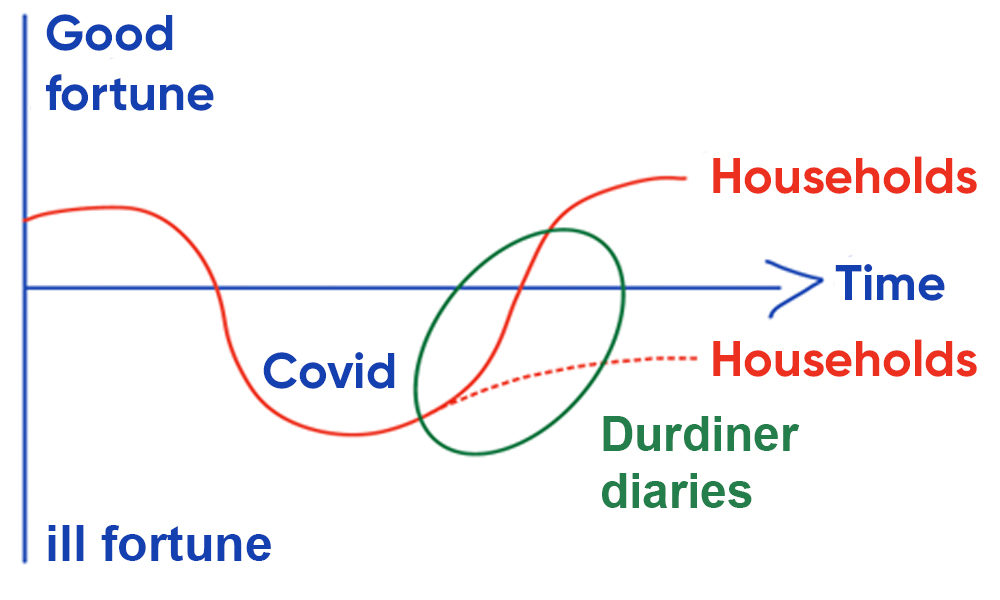

In our Durdiner Diaries project (in Bangla, Hard times diaries), we have been tracking ‘new poor’ households in Bangladesh, studying their experiences of life before, during and after Covid. These are households that were not poor before Covid, but the impact of the pandemic made them ‘fall into a hole’. We study their coping strategies to ‘get out of the hole’.

The overall picture from our study across rural, peri-urban, and urban areas suggests that people are taking numerous loans, working multiple jobs, and using multiple strategies to face the multiple crises since the pandemic, such as the economic downturn and rising cost of living.

Multiple crises and its impacts

While all households spoke about how Covid disrupted their lives economically, the impact of rising inflation is worrying them even more at present. Their conditions are made worse by other national and global economic disruptions. The return of international migrants, closure of local factories, and price hikes have led to small businesses going bust, increased unemployment, and school drop-outs. Households are unable to repay existing loans and they need more social security support.

For example, Moisul* currently runs a tea stall cum grocery store from a rented space. He worked in Malaysia for several years before his work place shut down due to Covid, leading to his return in 2020. He spent his savings from his time abroad on his sister’s wedding and father’s investments before the pandemic. Since his return, he has been running this shop, but with his family members struggling financially, they have had to sell jewellery and take loans for the shop. Rahman, who also runs a tea stall, used to run a computer–services store before Covid. He had purchased an expensive camera two days before the lockdowns began but was forced to close his shop. His finances were significantly affected, forcing him to look for jobs for a long time before setting up this tea stall.

Sobhan used to raise quails in his backyard, but when Covid hit he had to sell his birds at half of the price than before. After that he went to Saudi Arabia in 2021 but couldn’t do much due to lockdown and work permit issues. He took loans from several sources to go abroad. Since returning, he has struggled to bounce back and is currently trying to invest in different businesses like poultry and agriculture, but he lacks the financial resources.

Coping strategies to deal with multiple crises

Households have been using several strategies to survive in the face of all these crises. They have taken multiple loans, cut costs particularly in health and education, sold assets including land, work multiple jobs, and use formal and informal networks to access state social security. Bashir has run a bedding shop for decades but during the pandemic he started farming as well, since the closure of the local jute mill and the pandemic lockdown meant fewer customers. His inexperience in farming led him to lose money. He applied for an agricultural card through the local agricultural officer, which would give him free inputs – but the card did not work.

Relying on social networks, especially on the extended family and relatives, is a strategy many households adopt – but since the crises affect everyone, these networks can only provide limited assistance. Ameerah, a housewife in an urban slum was compelled to start work as a domestic worker. Her husband had bought an auto-rickshaw on loan a few months before the lockdown and to repay his loan he used to work during the lockdown, which was illegal. The police caught him and impounded his rickshaw. To repay the loan, Ameerah and her husband had to ask for money from their relatives, a microcredit NGO, and Ameerah’s employer. Still insufficient, she migrated to Jordan to work in a garment factory.

Stories from intermediaries

Besides households, we’re also interviewing local intermediaries, i.e., actors who help these households meet their governance needs by connecting them to the right public authorities. This allows us not only to triangulate information received from households but also gives us a broader perspective of the crises and coping strategies of the ‘new poor’. Our first round of interviews revealed that people have different routes to access intermediaries, depending on the context within which they live. The majority try to approach authorities through friends or relatives. For example, there are no formal intermediaries, such as bureaucrats or elected representatives, directly in touch with the residents in the slum that we are studying. Residents speak to informal actors or intermediaries, often affiliated with NGOs or political parties, who in turn speak to the formal authorities. Differences in political affiliation can be a hurdle in approaching some intermediaries.

Multiple intermediaries informed us that the middle class is struggling but is not able to access state support due to ineligibility: they aren’t poor enough. Additionally, they say, when these households are eligible, honour and shame prevent them from asking for assistance. A finding that was confirmed through our household interviews as well.

Intermediaries working with the local government shared that people approach them mainly for three purposes: to get government documentation; to access government support, particularly the social security programmes; and for dispute resolution. A couple of NGO representatives and one bureaucrat we interviewed noted an increase in both defaults on loans during Covid and reliance on government social security, since it is hard to get loans after failing to repay them.

One influential school headmaster observed that the lockdown led to an increase in child marriages and boys starting to work earlier. We witnessed this with one of our household respondents, who was forced to pull his underaged daughter out of a Bangla school and get her married because of his financial condition. Another bureaucrat we spoke to noted that several girls who dropped schools during the pandemic got married despite there being laws banning child marriage.

As we continue our research, we hope to follow these households in their pursuit of recovery, although there is no guarantee that they will recover. We’ll keep analysing their diverse coping strategies, their interactions with intermediaries, their successes and failures while trying to get out of the hole to provide useful inputs for actors working on improving governance and social protection.

*Names of the respondents have been pseudonymised in line with data protection rules (UK GDPR 2018).