Much attention has been given to the trafficking and exploitation of women and girls in Nepal and abroad. Criticism is often directed at informal businesses such as restaurants, folk music bars (known as dohoris), dance bars, massage parlours, guesthouses, and hotels – a collection of diverse businesses that, within Nepal, is referred to as the ‘Adult Entertainment Sector’ (‘AES’). Human trafficking is a heinous crime. However, some well-intentioned anti-trafficking strategies have resulted in stigmatisation of female workers, business owners and labour intermediaries also known as ‘brokers’.

Our research objective was to understand the experiences and hopes of urban Nepali ‘AES’ workers and labour intermediaries, in order to develop more effective policies and interventions to prevent human trafficking and labour and sex exploitation. The accompanying Policy Brief lays out recommendations to end human trafficking, sex and labour exploitation while supporting individuals, businesses and the Nepal economy to grow ethically and sustainably.

Hospitality, entertainment, and wellness sectors have provided work within a context of slow domestic job creation. Industrial development is challenging in a land-locked mountainous country bordering India and China. As a result, Nepal relies heavily on international remittances sent home mostly by male foreign labourers. These remittances make up almost a quarter of GNP. Female workers who often enter the labour force with a minimum level of education face wage gaps, discrimination, and sexual harassment within the country, and have faced legal restrictions to migrate internationally for work. Young women seeking work in Nepal are confined to sectors that will accept them. Apart from agriculture, this often means informal, small- or medium-sized venues in growing and poorly regulated sectors such as hospitality, entertainment, and wellness.

Our visual analysis of neighbourhoods with these businesses at various times of day found that there is no single ’AES’ sector in so-called ‘hotspots’. Rather we found that these venues, workers, and owners are integrated into the lives and geography of residential communities.

Women hand girls working in Nepali hospitality, entertainment, and wellness massage venues face well-documented abuse including sexual harassment, commercial sexual exploitation, forced alcohol consumption, and wage theft. There are huge differences between businesses and the services they provide. A massage can mean ayurvedic massage performed by a trained health professional or a sloppy leg rub with a happy ending. Similarly, a performer might have trained her/his vocal skills for years or be on stage mostly for their attractive looks. Working at night in a city, especially by women, is relatively new in a traditional agricultural society, and seen as a form of social transgression. Nepali people are diverse. But many have ambivalent attitudes towards female performers, especially when they work at night in venues, performing dohori or dancing for mostly male clients who drink alcohol.

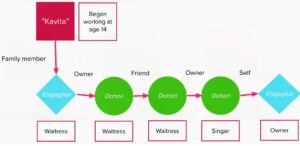

Using participatory approaches, we collected labour trajectories and work histories of 57 female and one transgender male workers with experience in Nepali and international ‘AES’ jobs and venues. Labour intermediaries or ‘brokers’ are individuals that connect a person seeking a job to an employer. Women and girls working in Nepali hospitality, entertainment, and massage venues rely on people that are close to them. Informal labour intermediaries are subject to suspicions of criminal activities, including trafficking, in a context of restrictive anti-trafficking and migration policies. In order to fill a gap in the literature we also interviewed 33 adults who identified themselves or were identified by others as labour intermediaries. Here is an example of a real anonymous work pathway of an ‘AES’ worker with a fictionalized name for privacy. A Khajaghar is a small restaurant serving Nepali food.

Workers reported a wide range of jobs/roles in their work history between 2001 and early 2022. ‘AES’ workers get most of their jobs through their family, long-term friends, and recent acquaintances. Our findings show that there are multiple and diverse labour trajectories for ‘AES’ workers in Nepal and for international work. Labour trajectories of ‘AES’ workers appear to be more like a web – individual threads that connect and separate through the type of venue, type of job, location, and type of labour intermediary. In contrast to the prevailing image of labour intermediaries as slippery exploiters, we learned that they see themselves as a trusted benefactor, a helper, a confidante, and a friend, who is mostly driven by the desire to help others to have a better life. This may be overly positive. However, workers we interviewed did not generally consider labour intermediaries to be responsible for the working conditions of the jobs they helped them obtain.

Workers reported labour exploitation, sexual exploitation, and human trafficking in worker and labour intermediary labour trajectories and experiences. Workers reported taking most jobs of their own accord, rather than being forced by labour intermediaries, but exploitation is widespread. Our findings reinforce other research showing that that human trafficking, sexual exploitation, and labour exploitation in the hospitality, entertainment, and wellness sectors both in Nepal and internationally is due to systematic economic and regulatory conditions, gender inequity and lack of enforcement rather than organised crime networks.

Information on how people find work is important to help distinguish between imperfect but well-intentioned and useful services that help people make a living, and fraudulent services and practices that intend to exploit and abuse workers. Male and female labour intermediaries, workers, and owners of AES venues have fluid identities in informal, growing, and highly competitive sectors. Their roles can overlap each other simultaneously or at different moments in their life. They are men and women who came to entertainment and hospitality at a young age, developing practical skills, building a network of trusted people, and learning to be savvy about whom to trust and whom to avoid.

Incorrect perceptions of how workers find, keep, and change jobs have perpetuated anti-trafficking policies and interventions focused on ‘AES hotspots’ and unscrupulous organised labour intermediaries that do not mirror reality. Moving forward, government policy makers, donors and NGOs should ensure that policies and interventions to end human trafficking and support women and girls to find safe, decent work are based on evidence of the complexity of the businesses and workers that make up the Nepali hospitality, entertainment, and wellness sectors.