Migrant workers in Vietnam make up 7.3 per cent of the population. Despite rapid economic growth, they suffer from precarious working conditions and food insecurity, which Covid-19 control measures have exacerbated. Urgent action is needed to improve migrant workers’ access to nutritious food during crises and increase resilience to future economic shocks through:

- short-term responses that provide nutritious food;

- improving living conditions through effective enforcement of existing policies;

- expanding coverage of the government social safety net; and

- progressive reform of labour law to reduce their vulnerability to job loss and increase their bargaining power.

Key messages

- During the pandemic, 81 per cent of ‘free labourers’ – workers without contracts – and 58 per cent of workers in industrial zones (IZs) lost their jobs. Earnings decreased significantly: free labourers received 14 per cent of their pre-pandemic incomes.

- Workers’ diets were poor due to income constraints and inadequate living conditions – affordable foods could be stored at room temperature but lacked nutrition.

- Government wage compensation and unemployment payments did not reach free labourers and were insufficient for IZ workers.

- Short-term crisis response must provide food to workers that has a balance of micro- and macronutrients.

- The government and migrant workers need a long-term strategy to improve workers’ resilience, ensuring a minimum standard of living and labour rights, and formalising the informal economy.

Urgent action is needed to improve migrant workers’ access to nutritional food during crises.

Background

This Policy Briefing is based on evidence collected as part of the Covid Collective project by researchers at the Vietnamese National University of Agriculture (VNUA) and the Institute of Development Studies (IDS) between August 2021 and March 2022. The study investigated food and nutrition security among migrant workers in the capital Hanoi and Bac Ninh province during Covid-19 lockdowns. Vietnam has made impressive progress towards eradicating food insecurity; but an estimated 6.4 million people who migrated to cities for work, many of whom are ethnic minorities, still experience food insecurity.

Migrants are vulnerable to economic shocks such as Covid-19-related lockdown measures for two reasons. First, their migrant status prevents them from accessing critical public services such as health care, education, housing and social security; private safety nets exist (e.g. voluntary social insurance), but are unaffordable for many. Second, migrant workers’ jobs tend to be precarious and informal, which reduces their bargaining power with employers; during the pandemic, it prevented them from accessing government monetary support. This study investigated how lockdown measures to slow the spread of Covid-19 affected migrant workers’ incomes, living conditions and access to nutritious food, and food security.

We identified migrants with and without formal contractual arrangements, interviewing workers without contracts – so-called ‘free labourers’ – in the capital Hanoi. In Bac Ninh province, we interviewed workers in special industrial zones (IZs) contracted by Vietnamese and foreign companies.

Migrant workers experienced significant income reduction

Since April 2020, 81 per cent of free labourers and 58 per cent of IZ workers reported losing their job. Companies in IZs, especially those connected to overseas markets, significantly reduced workloads and employees took turns working. Prior to the pandemic, many worked overtime to earn extra income; when this was not possible, their income decreased significantly. The situation for free labourers in Hanoi was more precarious than in IZs because they did not have formal contracts beforehand. Lockdown measures reduced activities in non-essential businesses and services; and contractors laid off workers without compensation. Street food vendors, many of whom are free labourers, struggled to adapt to sudden and unexpected government policy changes. Other food sector workers (e.g. cleaners, labourers, security guards) reduced their workloads because markets were closed.

Changes in employment situation are reflected in monthly income figures. Before the pandemic, both free labourers and IZ workers earned an average 7–8 million Vietnamese dong (300–350 United States dollars) per month, which is typical in Vietnam for workers without a higher education and job-specific skills. During lockdowns, both groups lost income, but particularly free labourers: in the latest lockdown, IZ workers and free labourers earned roughly 40 per cent and 14 per cent of their pre-pandemic incomes, respectively.

Food security was low, particularly among free labourers

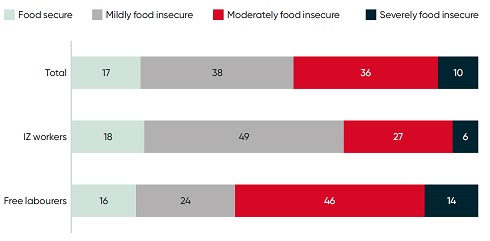

To reduce spending, workers most often said they ate less, followed by reducing remittances they sent home. They tended to sacrifice food security to maximise remittances. Interviewees’ food security was low overall, with 36 per cent and 10 per cent moderately and severely food insecure, respectively. Food security was considerably lower among free labourers than IZ workers: 46 per cent and 14 per cent of free labourers were moderately and severely food insecure, respectively, versus 27 per cent and 6 per cent of IZ workers.

This contrasted with a 2019 International Food Policy Research Institute report, which found that 16.1 per cent and 1.8 per cent of people were moderately and severely food insecure, respectively. Five per cent of free labourers reported not eating for a whole day; and nearly 70 per cent of both groups of workers ate only a few kinds of foods because of lack of money. Only 34 per cent reported having a fridge where they lived and they were unable to buy fresh food every day when markets were closed during lockdowns. As the lockdowns coincided with the summer (May–September) in northern Vietnam, workers mostly purchased food that could be stored at room temperature, such as instant noodles and rice, significantly reducing the nutritional content of meals.

Figure 1 Workers’ food security (%)

Source: Authors’ own.

Public support and social protection measures did not reach informal workers

IZ workers were entitled to 50–70 per cent of salary compensation and government-funded unemployment insurance because they had formal contracts with companies in IZs. They faced few bureaucratic hurdles in accessing these funds, which were transferred to their bank accounts automatically. However, the amount of compensation was calculated based on their basic salary, excluding overtime pay. Therefore, their income during lockdowns was significantly lower than before the pandemic.

It was not easy for free labourers to get monetary support due to the complexity of the paperwork and legal procedures needed to prove they had been made unemployed because of the pandemic. Some reported selling their mobile phones and taking out loans from private mortgage service providers (illegally) against their ID cards to buy food. Street food vendors collected leftover fruit, vegetables, and other food from markets for their meals.

Both groups of migrants got food from civil society organisations. Individual owners of workers’ residences provided food and reduced rents. Migrants also borrowed money from colleagues, friends, and relatives to cover their own expenses and remittances. Free labourers also asked their employers for support.

Policy recommendations

- Ensure short-term responses provide nutritious food to workers. Migrant workers spent less on food to maximise remittances, significantly reducing the quantity and nutritional content of meals. During crises, we recommend employers provide ample, nutritious and safe meals, as well as wages, particularly for free labourers in the informal sector when their livelihoods are strained. Also, the government must set minimum standards for the amount, nutrition, and safety of foods for migrant workers and ensure employers and meal providers adhere to them.

- Improve living conditions by enforcing existing rules. Living conditions were poor overall and cooking environments – spaces many people often shared – were inadequate to encourage healthy diets. Lack of refrigeration prevented people from buying perishable foods, such as meat, fruit and vegetables, particularly in the summer. Therefore, we suggest the government enforces regulations on minimum standards for spaces rented to migrants and imposes stricter sanctions for violating them.

- Expand coverage of social safety nets to migrant workers. Support for vulnerable people must shift from short-term crisis response to longer-term resilience building through broadening the range of social protection measures for contracted workers; and radical reform of the social security system to increase benefits for informal workers.

- Reform regulations to improve labour rights. During the pandemic, employers laid off workers without justification and at short notice. The government needs to formulate clearer legal grounds for employers to dismiss workers in unforeseen circumstances. Moreover, labour law reforms and their effective enforcement should empower workers’ collective organisations, such as trade unions, to increase their bargaining power. In addition, the government and migrant workers need to develop a long-term strategy that formalises the informal sector, reducing workers’ vulnerability and improving labour rights.

Further reading

Dien, N.T. et al. (2015) ‘Duality of Migration Lives: Gendered Migration and Agricultural Production in Red River Delta Region, Vietnam’, paper presented in the Les 9es Journées de recherches en sciences socials, 10–11 December 2015, Nancy, France

Ebata, A. et al. (2022, forthcoming) How Did Covid-19 Affect Food and Nutrition Security of Migrant Workers in Northern Vietnam?, IDS Working Paper, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies

General Statistics Office (2021) Report on the Impacts of Covid-19 Pandemic on the Labour and Employment, First Quarter, 2021, press communication, Hanoi: Ministry of Investment and Planning

Kim, C. et al. (2021) Production, Consumption, and Food Security in Viet Nam Diagnostic Overview, Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute

Credits

This IDS Policy Briefing was written by Nguyen Thi Dien, Nguyen Thi Minh Hanh and Nguyen Thi Minh Khue, Vietnamese National University of Agriculture and Ayako Ebata, Institute of Development Studies. It was produced as part of the Covid Collective, supported by the UK government’s Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO). The Covid Collective cannot be held responsible for errors, omissions, or any consequences arising from the use of information contained. Any views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of FCDO, the Covid Collective, IDS or any other contributing organisation.

© Institute of Development Studies 2022.

© Crown Copyright 2022.

This is an Open Access article distributed for non-commercial purposes under the terms of the Open Government Licence 3.0, which permits use, copying, publication, distribution and adaptation, provided the original authors and source are credited and the work is not used for commercial purposes.