Multiple aid agencies often try to support change in the same places, at the same time, and with similar actors. Surprisingly, their interactions and combined effects are rarely explored. This Policy Briefing describes findings from research conducted on recent aid programmes that overlapped in Mozambique, Nigeria, and Pakistan, and from a webinar with UK Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO) advisors and practitioners. The research found three distinct categories of ‘interaction effects’: synergy, parallel play, and disconnect. We explore how using an ‘interaction effects’ lens in practice could inform aid agency strategies and programming.

Key messages

- Conventional aid programme analysis – including evaluation – tends to reflect a narrow, siloed focus on single aid programmes, neglecting the interactions across programmes.

- Identifying the direct and indirect interaction effects of overlapping aid programmes offers a different ‘way of seeing’ the impacts, that goes beyond the normal donor coordination and harmonisation approaches.

- Overlapping aid programmes can reinforce one another, miss opportunities, or undermine one another. We call these scenarios synergy, parallel play, and disconnect.

- Identifying donor interaction effects could add value to aid strategies – allowing development actors to avoid conflicting actions and siloed working and achieve more through synergy with others.

About the research

Our research started from the hypothesis that governance reform aid programmes that overlapped in geographical territories were likely to have important interactions that affected their outcomes. We explored this in three countries – Mozambique, Nigeria, and Pakistan – as part of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA) research programme. All three countries are significant recipients of governance-focused international aid from multiple parties and are therefore places where we might expect to see aid programme interactions. Ongoing conflicts in parts of each country complicate these efforts.

We selected in each country one FCDO-financed programme that aimed to enhance state accountability to citizens. We paired each of these with another aid programme that overlapped for some of the implementation period and shared accountability goals.1 The ‘paired’ programmes in Pakistan were both funded by FCDO whilst the programmes selected in Nigeria and Mozambique included one funded by another aid agency. Researchers in each country interviewed project stakeholders at multiple levels. Insights from these case studies led us to develop the conceptual lens on interaction effects that we share here.

Source: © IDS and Itad

Developing an interaction effects lens

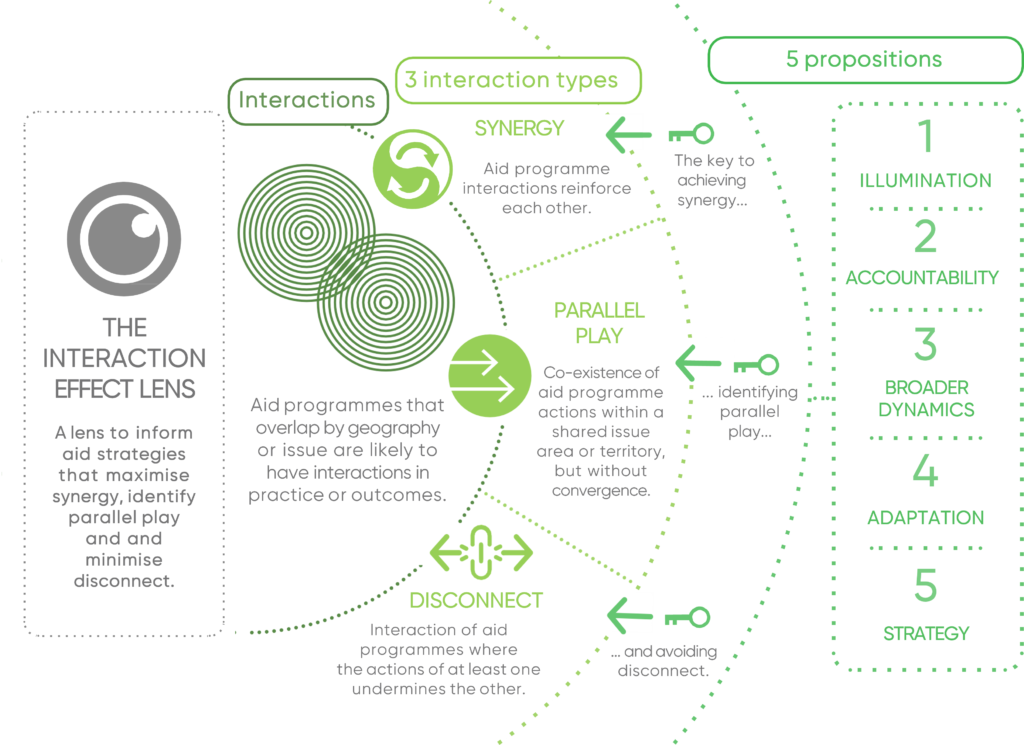

Different international aid programmes that involve overlapping issues, actors, and territories can have interaction effects in those shared arenas. Interaction effects are defined as the results of these overlaps in aid programme actions. Interaction effects can happen with or without direct contact between those working in aid agencies.

The research takes into account both direct and indirect interaction effects. Direct effects come about through contact between aid programme donors. Indirect effects arise through other related actors such as the programmes’ grantees or government actors the programmes seek to influence. While our research focused on the interaction effects across just two programmes in each country, this lens could be applied to larger numbers of programmes as well. It also seems highly relevant for sectors other than the governance programmes we looked at.

We found that overlaps between aid programmes’ actions can have three possible kinds of interaction effects:

- Synergy: one programme’s actions reinforce the other’s;

- Parallel play: aid programme actions co-exist within a shared issue area or territory, without reinforcement or convergence (null category);

- Disconnect: the actions of at least one programme undermine the other.

These categories emerged inductively from the research and, in turn, led to developing a lens that brings together the distinctions between direct and indirect interactions, and the three kinds of interaction effects observed.

Source: © IDS and Itad

Key findings

Our research identified a number of cases of synergy and parallel play, and one of disconnect.

Synergies were achieved where:

- One aid programme clearly capitalised on the institutional memory and history of engagement by another programme. This occurred in Pakistan where the Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan (CDIP) programme took up and built on programme infrastructure, human resource investments, and networks built by the earlier AAWAZ Voice and Accountability Programme. In Nigeria, subnational states proved eligible for World Bank support because of previous work on state capacity and state–civil society coalitions undertaken by the FCDO Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn (PERL) programme. We also observed it in Mozambique, where local civil society organisations met the Action for Inclusive and Responsive Governance (AGIR) programme’s fairly demanding eligibility criteria for its core support and project funding thanks to the Civil Society Support Mechanism (MASC) programme’s earlier investments, which had enabled them to gain formal registered status and build their administrative and grant management capacities.

- Organisations which were implementers and/or grantees of more than one programme created efficiencies. This occurred in two consecutive programmes in the case of Pakistan, where AAWAZ’s implementer then developed and implemented CDIP, basing it on AAWAZ systems and structures. We also observed this in the two simultaneous programmes in Mozambique, where some grantees of both programmes integrated their approaches to managing them, without the donors’ involvement.

- At least one of the aid programmes pursued a deliberately adaptive approach. This was the case in Pakistan where AAWAZ created new spaces for citizen empowerment in parallel to non-functioning state spaces, and CDIP later re-purposed the AAWAZ-supported Aagahi (citizen awareness) centres to underpin its efforts to expand democratic political spaces. In Nigeria, PERL’s adaptive design enabled it to identify and respond to the opportunities provided by the World Bank’s States Fiscal Transparency, Accountability and Sustainability’s (SFTAS) new incentives for public sector reform.

Parallel play occurred where:

- Aid programmes did not effectively take advantage of the other’s operating space or experiences, or of opportunities presented. In Nigeria, the SFTAS one-size-fits-all model did not align with the depth of PERL’s adaptive support for citizen engagement. Consequently, SFTAS did not position itself to take advantage of the opportunities that PERL had created by empowering citizens to hold state actors to account. In Mozambique, AGIR and MASC worked in parallel without forging a common vision or joint efforts, which would have afforded opportunities to reinforce one another’s progress towards their shared objectives. Instead, they created segmentation along the lines of different funding sources and competing donor identities.

- One aid donor or implementer was so bound by its own rules, foundations, and procedures that it failed to recognise or interact with those of the other actor. In Nigeria, despite the two programmes’ significant thematic and geographic overlap, opportunities were missed to collaborate on shared targets – both in relation to the ambition of those targets, and their measures of success.

Disconnect occurred where:

- One aid programme’s narrow results focus undermined another’s long-term efforts. The formulaic approach taken by SFTAS in Jigawa State, Nigeria, to securing a ‘model’ procurement law led to the bar getting set lower than PERL’s previous efforts had already set it in practice. This potentially rolled back progress, as well as introducing new loopholes that could reduce civil society engagement.

Wider implications

Five broad propositions emerge from our interaction effects lens:

- Illumination: examining aid programmes’ overlapping issue areas and subnational territories reveals interaction effects between aid actions that would not be visible if any one aid programme was studied in isolation, as is commonly the case.

- Accountability: analysing aid actions for accountability underscores the relevance of the concept of the ‘accountability ecosystem’. Our understanding of that ecosystem is broadened when the full range of international actors is taken into account.

- Broader dynamics: whilst we looked at interaction effects of programmes with similar aims, the interaction effects lens can also help see the combined impacts of actions in different sectors, such as health and education.

- Adaptation: the interaction effects lens helps to broaden the scope of adaptive management approaches to include the possibility that one aid programme may or may not adapt to others’ actions, as well.

- Strategy: the interaction effects lens can inform aid strategies that maximise synergy, while identifying and addressing parallel play and minimising disconnects. But it requires incentivising aid programme staff – including donors!

The interaction effects lens and the above propositions were discussed at a webinar in January 2022 with FCDO governance advisors and several implementers of FCDO aid programmes.

Overall, the lens resonated with participants, who could see more parallel play and disconnect from their own experience. They noted that sometimes intentions to act synergistically ended up faltering and producing parallel play. They also felt the lens could be relevant to looking at interaction effects within the same donor (i.e. FCDO) across different sectors. It was also seen as critical to look at interaction effects from a recipient view (i.e. host governments and civil society) as well as a donor view.

Webinar participants considered that synergies are more likely to occur when there is a single-issue focus (e.g. around elections or responding to a specific crisis) or a higher-level goal (e.g. donor support to an agreed peace deal). They also felt synergies are more likely where there are shared frameworks and analysis amongst donors, but this requires pushing for a shared, common analysis and actively creating a space to identify and raise issues around disconnects and missed opportunities. This takes time, effort, and commitment. It requires actors to consider incentives which go beyond their own narrow donor requirements. This calls for the right skills and experience among aid programme architects and implementers to build and maintain relationships to keep synergies ‘on track’, while recognising that the ‘plumbing’ (e.g. business cases, procurement rules, reporting requirements, and rigid and not adaptive processes) can hinder aid staff from seeing the bigger picture of the interaction effects in the wider aid ecosystem.

Policy recommendations

Aid policymakers and practitioners would benefit from an understanding of the interaction effects within and between their aid programmes, not least to encourage a more coherent use of aid money.

Employing an interaction effects lens can help to inform aid strategies that maximise synergy, identify parallel play, and minimise disconnect.

Aid programme architects should:

- Write business cases and project plans that cover how their actions will interact with others, and adapt to changes in what others are doing in real time, identifying opportunities for synergy.

- Push for a broader common analysis with other aid actors at the design phase, to bring about shared or explicit understandings of problems and their causes.

- Be alert to the human assets and capacities being built by other programmes and proactively seek to build on them rather than starting afresh.

- Be prepared to pool resources and combine efforts to undertake multi-programme research and evaluation at strategic points – and be better value for money.

Implementers of aid programmes should:

- Invest in the ‘peripheral vision’ needed to see what is happening outside of their direct sphere of influence as a result of other aid actors, and update their theories of change and action to these shifts in the context.

- Watch out particularly for other efforts that lower the bar or set less ambitious targets for reform – and opportunities to avoid that.

- Build capacity for adaptation and course correction into programming, and influence other actors to encourage adaptation in their programming.

- Engage staff and partners who know the landscape well and can maximise indirect interactions between aid programme actions.

Evaluators and researchers of aid programmes should:

- Actively investigate and bring to the fore interaction effects, to encourage more open debate with multiple actors involved in accountability reforms and foster deeper lesson learning.

- Share real-time findings during programme implementation, not only retrospectively, and as openly as possible, to head off potential disconnects, and find opportunities for synergy.

Notes

1 The aid programmes covered were, in Nigeria: Partnership to Engage, Reform and Learn (PERL) and World Bank-funded States Fiscal Transparency, Accountability and Sustainability (SFTAS); in Pakistan: AAWAZ Voice and Accountability Programme and Consolidating Democracy in Pakistan (CDIP); and in Mozambique: SIDA-funded Action for Inclusive and Responsive Governance (AGIR) and FCDO-funded Civil Society Support Mechanism (MASC).

Further reading

Aremu, F.A. (2022) Donor Action for Empowerment and Accountability in Nigeria, IDS Working Paper 565, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, DOI: 10.19088/IDS.2022.015

Khan, A. and Qidwai, K. (2021) Donor Action in Pakistan: A Comparative Case Study of CDIP and AAWAZ, IDS Working Paper 549, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, DOI: 10.19088/IDS.2021.025

Burge, R. and McGee, R. (2022) New Insights on Adaptive Management in Aid Programming, IDS Opinion, 17 March

Credits

This IDS Policy Briefing was written by Richard Burge, Rachel Nadelman, Rosie McGee, Jonathan Fox and Colin Anderson. It was edited by Emilie Wilson and supported by Jenny Edwards. It was produced as part of the Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA) research programme, funded with UK Aid from the UK government (FCDO). The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of IDS or the UK government.

© Institute of Development Studies 2022.

This is an Open Access briefing distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.