Over the last two decades great strides have been made in terms of holding extractive industries accountable. As demonstrated at the Global Assembly of Publish What You Pay (PWYP), which I attended recently in Dakar, Senegal, more information than ever about revenue flows to governments from the oil gas and mining industries is now publicly available. But new research suggests that such information disclosure, while important, is by itself not enough to hold companies to account, and address corruption.

Men, women (often with babies strapped on their backs), work in teams to to carry out all facets of this tin mining. On a good day a team of 10 will have have harvested enough tin which they will sell for the equivalent of $140. Credit: Dave Klassen Flickr CC BY 2.0

Issues of accountability relating to the extractive industries are global and longstanding. Through my own work with a citizens research project many years ago on land ownership in the US mining region Appalachia, shocking findings emerged. In key coal producing areas, something like 80 per cent of the minerals were owned by wealthy absentee companies, who paid less than four per cent of the local taxes. As a result, the schools, services, roads and infrastructure of these communities, which sat on top of valuable mining lands, remained poor. Getting information on these companies, and what they paid or should pay to local governments was a huge and challenging task.

Fast forwarding to the current day, public information about extractive industries is much more readily available. Over its 16-year history, PWYP, as well as its spinoff, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) have made impressive gains, with over 50 countries now producing publicly accessible detailed reports on the revenues flowing to government from the oil, gas and mining industries.

The theory of change of these important initiatives is that through making information available, the public will be able to hold these companies more accountable for their actions, and diminish corruption.

Lessons from Mozambique – information disclosure and accountability

However, a recent study in Mozambique by researchers Nicholas Aworti and Adriano Adriano Nuvunga questions this assumption. Supported by the Action for Empowerment and Accountability (A4EA) Research Programme, the research explored why greater transparency of information has not necessarily led to greater social and political action for accountability.

Like many countries in Africa, Mozambique is experiencing massive outside investments in recently discovered natural resources, including rich deposits of natural gas and oil, as well as coal and other minerals. Over the last decade, NGOs like the Centre for Public Integrity, who helped facilitate the study, have done brave and often pioneering work to elicit information on the extractive industry, and to publish it in hard-hitting reports, widely reported in the press, and discussed at high-level stakeholder meetings.

Yet, as Aworti and Nuvunga summarise in a policy brief based on their research, ‘neither these numerous investigative reports nor the EITI validation reports have inspired social and political action such as public protest or state prosecution.’ Corruption continues, and despite the newfound mineral wealth, the country remains one of the poorest in Africa.

The authors ask, ‘If information disclosure has not been enough to galvanise citizen and institutional action, what could be the reason?’ The research found 18 other factors that affect whether information leads to action, including the quality of the information and how it is disseminated, the degree of citizen empowerment, the nature of the political regime, and the role of external donors in insisting on accountability.

New approaches to accountability in relation to extractive industries

The research and the challenges highlighted by the Mozambique case point to the need for new approaches. At the Global Assembly in Dakar several hundred of PYWP’s more than 700 members from 45 countries gathered to discuss and to approve the organisation’s next strategic plan. Among other points, the plan calls for going beyond transparency – to more intentionally use information to foster and promote citizen action, strengthen grassroots participation and voice on mining issues, and improve links with other related civil society movements working on gender, climate and tax justice in the extractives field.

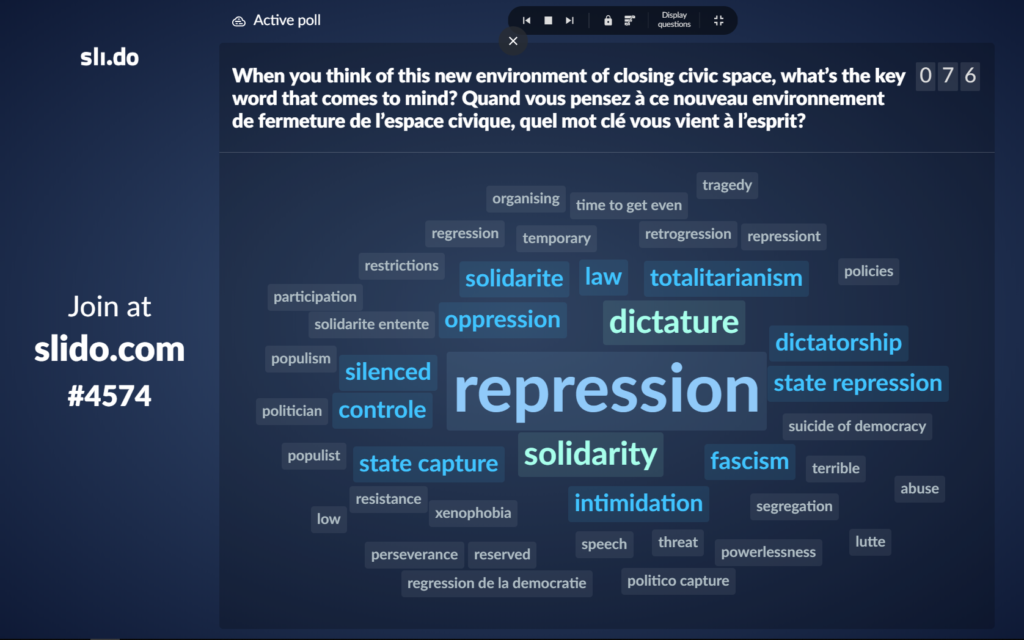

Coming at a time where increasing push back and repression threaten the space for citizens to speak truth to power, this is a bold call. I chaired two sessions with PWYP activists who had been beaten, jailed, threatened or exiled for challenging mining companies, and 70 per cent of the delegates at the conference said their work had been affected by this more repressive environment.

In such settings, there are no quick and easy answers for how to ensure that the long chain between transparency and accountability can be shortened. But from my experiences in organising around mining companies in the US and from Nicholas’ and Adriano’s research, there are several strategies that come to mind:

- Find new ways to communicate our work. The important study by Nicholas and Adriano shows that capital-city based intellectuals pay a great deal of attention to information communicated in forms with which we are comfortable such as dense technical reports. But other actors don’t, especially important constituencies like rural youth in Mozambique. So we need different wants of communicating. Music has been a powerful mobiliser and communicator on corruption issues, as another project in the A4EA programme on the role of hip-hop as a tool to share information has demonstrated. Hip-hop lyrics on what extractives pay or don’t pay anyone?

- Use local framings. At a meeting in Mozambique, a Nigerian sociologist, John Agbonifo, described how Ogoni leaders used the framing of miideekor in the Ogoni struggle to hold the oil companies to account in the Niger Delta. Miideekor referred to a local labour practice where the owners of palm trees would hire their fields to palm wine tappers. The tappers could keep the produce for the first four days for themselves, but the fifth was the landlord’s miideekor. To renege on the miideekor was culturally unacceptable. Using this concept to explain the responsibilities of the oil companies to pay their miideekor to the local communities helped to build the movement.

- Build economic literacy at the local level. Paulo Freire, used awareness building literacy programmes amongst the rural poor in Brazil and elsewhere to build the base for social movements against the powerful latifundia (agrarian landlords). Is there scope for those who are skilled at publishing information from above to partner with groups who can build popular education campaigns from below? Could donors who support work on governance and transparency in the extractives sector also support economic literacy and empowerment of affected rural communities?

- Use information to mobilise. As my friend Lisa VeneKlassen at Just Associates always says, in addition to transparency we need ‘knowledge plus noise’ or widespread collective action. Over forty years ago, my first study of the lack of transparency of mining communities in my home state Tennessee led to a dozen brave citizens, meeting in a church basement, to decide to use the information to take legal action against the state for its failure to collect taxes from mining companies. That action led to a new grassroots organisation– Statewide Organizing for Community Empowerment (SOCM) – which now represents communities across Tennessee, always watching and acting on the mining industry’s next move. A later study of who owned the land across the region also prompted the formation of a similar group, Kentuckians For the Commonwealth (KFTC). Several decades later, these strong, grassroots organisations – both founded on the principle of putting information into action – continue to organise to challenge the power of the extractive industry.

- Build alliances – civil society can’t do it alone. But as Jonathan Fox reminds us, we need ‘voice with teeth’ – the ability not only to demand accountability from below, but also the ability to enforce it through larger political incentives, legal frameworks, and electoral muscle. Where the political party and other elites are so strong and powerful, as in Mozambique, this is a challenge, but new accountability coalitions can and must be formed.

Campaigns like PWYP and EITI have done a huge amount to gain greater transparency of revenues. Now they – and the donors who support them – can also do more help to convert information to action, support mobilisation from below, and help shape the larger political incentives that can give teeth to voice. In a time of increasing threats against those who use information to challenge powerful extractive companies, this work is more important than ever.