This is the second blog in our series ‘Lessons on using Contribution Analysis for impact evaluation’. In our first blog, we introduced Contribution Analysis (CA) as an overarching approach to theory-based evaluation and the idea of causal hotpots as a way to zoom in, unpack and make the hard choices of where to focus evaluation research. Identifying specific links in the theory of change (ToC) with specific evaluation questions enables you to then choose appropriate methods.

We have applied the approach in diverse settings, testing how robust Contribution Analysis can really be. Here we walk you through an example.

Evaluating participatory research as an intervention

We apply CA in programmes that use participatory, co-produced research as an intervention into complex development challenges. In evaluating these interventions, we want to understand if and how marginalised and excluded populations use their own experience and knowledge to co-produce alternative development trajectories. The project activities are clear, but many outcomes are unknown because they are generated through engagement with stakeholders in context. We know what the broad issues of concern are at the outset, but the purpose of the research is to enable solutions to emerge from the ground, so by design we do not know at the outset what the solutions are and consequently, what the detailed pathways to impact will be.

This is the case in the Child Labour Action Research Innovation in South and Southeast Asia (CLARISSA) programme – a large scale action research programme focused on the drivers of the worst forms of child labour (WFCL). CLARISSA is designing and implementing child-centred action research on the lived realities of working children, and the social norms, urban neighbourhood and business and supply chain dynamics in the leather sector in Dhaka, Bangladesh and the adult entertainment sector in Kathmandu, Nepal. The resulting nuanced and systemic understanding of what drives children into WFCL becomes the basis for action research groups engaging in data collection and analysis to then generate innovative solutions by and for children, their parents and guardians, business owners and other stakeholders.

Moving from initial to causal theories of change

The programme’s initial theory of change – representing our best evidenced guess – provided a broad direction of travel and enabled building of operational plans in country around specific areas of focus. It reflects the necessary broad emphasis in the early phases of planning the participatory activities with children. Initial scoping and mapping identified the leather supply chain in Hazaribagh in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and the adult entertainment sector in clustered neighbourhoods in Kathmandu, Nepal, as focused areas of intervention.

With clarity on specific sectors and the entry points for participatory research, we then detailed a causal ToC around Participatory Action Research (PAR) as the main intervention modality (there are other areas and types of research that will work alongside PAR that have their own causal ToCs). Engagement with programme teams in country and across, use of insights from further scoping studies, formal evidence about PAR, and experiential knowledge of partners working with children in context all contributed. Through this process of co-production, we have now identified three causal hotspots shown as red circles in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Causal hotspots identified for CLARISSA evaluation

The programme activities start with the collection of 400 life stories of children working in the WFCL, followed by their participatory analysis by children leading into the identification of specific PAR groups, and in parallel, the implementation of children’s advocacy groups. Activities implemented by the PAR groups are shown in blue boxes. The expected immediate outcomes from the PAR groups include better understanding of what drives WFCL by children (and others), as well as evidence of effectiveness of actions, and an increase in the agency of children to change their own situation. The evidence is then used by the children’s advocacy groups that, together with other engagement activities leads to policy influencing that eventually results in the reduction of children in WFCL far beyond the programme timeframe.

Identifying hotspots and detailing evaluation research

The first hotspot is the inclusion of children in the life story collection and analysis process. Using the life story collection and analysis process to identify PAR groups is novel and has not yet been evaluated robustly (evidence is lacking rather than contested). IDS, the lead partner in the CLARISSA Consortium is interested in understanding how the methodology works, while NGO partners who are focused largely on working with children are interested in the effectiveness of the child centredness (all partners agree this is a hotspot).

Specific evaluation questions include: What outcomes does participating in life story collection and analysis processes generate for the children? And, how, in what contexts, and for whom are these outcomes generated (or not generated)?

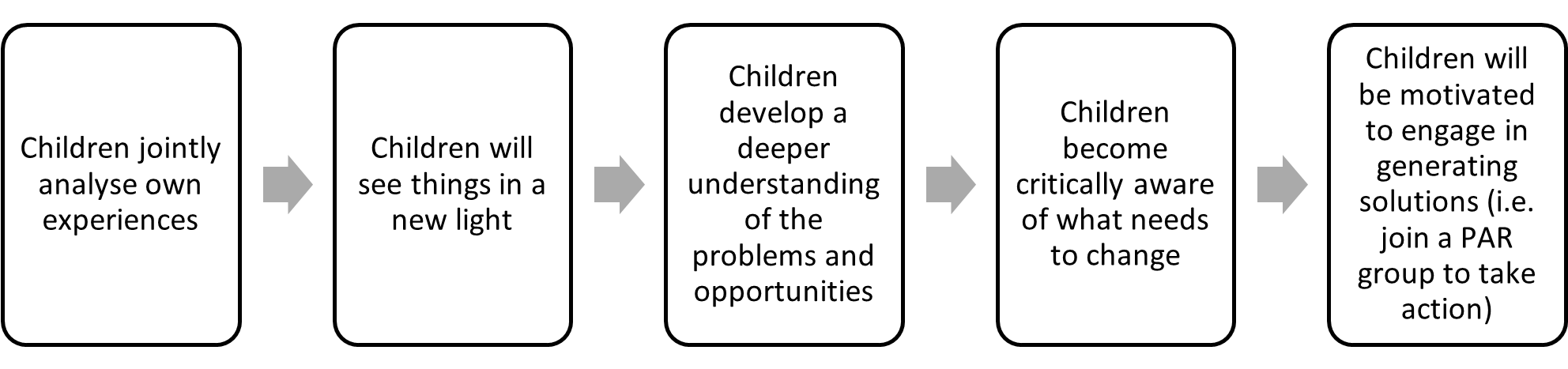

Zooming in to a more detailed view of the causal configuration was supported by the Rapid Realist Review conducted on if and how PAR generates innovation – and in particular one of the initial programme theories on ‘conscientization’ (see Fig 2 for simplified version). Specific data collection methods include process documentation and interviews with children, as well as after action reviews of the programme team.

Figure 2 – Conscientisation initial programme theory (simplified)

Transcript of the information contained in the image above (figure 2):

Box 1. Children jointly analyse own experiences, leading to

Box 2. Children will see things in a new light, leading to

Box 3. Children develop a deeper understanding of the problems and opportunities, leading to

Box 4. Children become critically aware of what needs to change, leading to

Box 5. Children will be motivated to engage in generating solutions (i.e. join a PAR group to take action)

The second hotspot includes a more detailed view of the inner working of the PAR groups as engines of innovation. This is a hotspot because all partners want to learn from using this methodology as an alternative to other programming modalities, and in particular the donor, given their investment in this innovation programme. No consolidated evidence base about why and how PAR works exists in the development sector, and in the context of child labour programming, there is little experience and no evidence that we are aware of.

The evaluation question is, in what contexts and for whom can PAR generate effective innovations to tackle the worst forms of child labour?

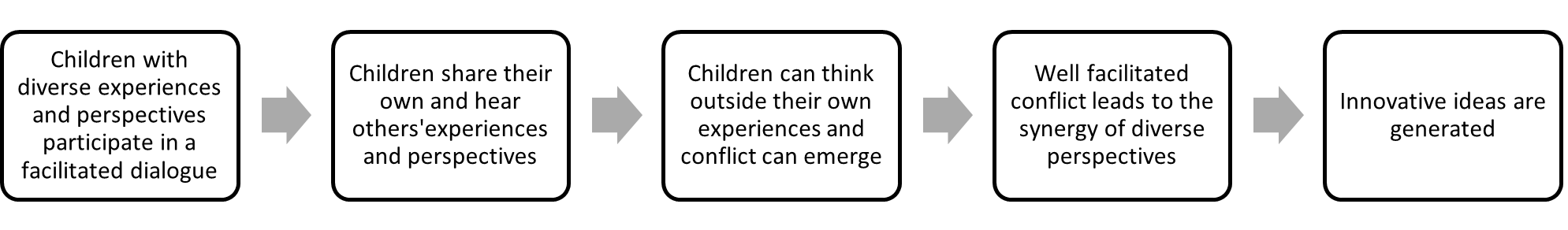

The Rapid Realist Review identified three main initial programme theories which provide entry points (through context-mechanisms-outcome configurations) for data collection for the realist evaluation methodology that will be used. In addition to the programme theory on conscientisation mentioned above, these programme theories are about diversity (Figure 3) and praxis (Figure 4).

Figure 3 – Diversity initial programme theory (simplified)

Transcript of the information contained in the image above (figure 3):

Box 1: Children with diverse experiences and perspectives participate in a facilitated dialogue, leads to

Box 2: Children share their own and hear others’ experiences and perspectives, leads to

Box 3: Children can think outside their own experiences and conflict can emerge, leads to

Box 4: Well facilitated conflict leads to the synergy of diverse perspectives, leads to

Box 5: Innovative ideas are generated

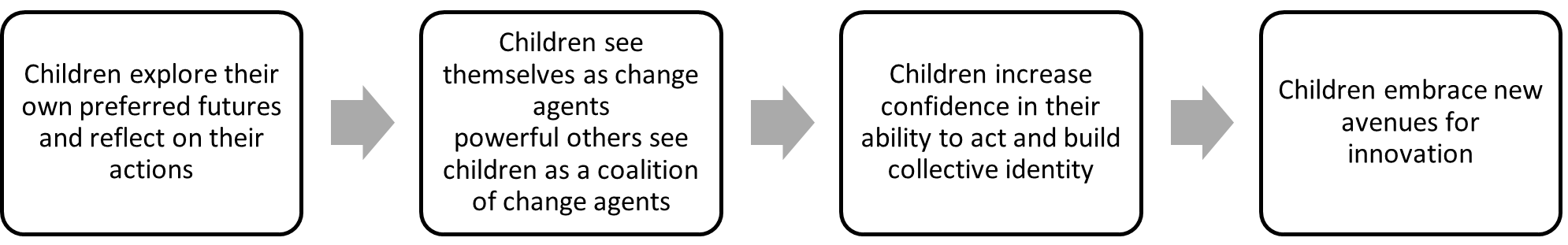

Figure 4 - Praxis initial programme theory (simplified)

Transcript of the information contained in the image above (figure 4):

Box 1. Children explore their own preferred futures and reflect on their actions

Box 2. Children see themselves as change agents powerful others see children as a coalition of change agents

Box 3. Children increase confidence in their ability to act and build collective identity

Box 4. Children embrace new avenues for innovation

The third hotspot focuses on if and in what ways including children in advocacy activities leads to more effective advocacy. This is of particular interest to some of the partners who have been developing child-led advocacy initiatives and training material, but have had little opportunity to evaluate the work rigorously. The evaluation question is, in what ways does involving children directly in advocacy activities shape the advocacy messaging and the types of outcomes it can contribute to?

Zooming in is aided by combining the advocacy coalition theory (and links to the praxis theory) and the policy window theories, two social science theories of change that are used as global theories for advocacy and policy change efforts. Data collection for this part of the evaluation is still being detailed as in country advocacy plans take shape.

Focusing now and evolving later

Focusing on three hotspots, situates our evaluation within the sphere of influence of the programme, meaning that we do not intend to evaluate contribution of PAR to changes in prevalence of WFCL – the end impact. For some partners in the programme, letting go of evaluating end impact is uncomfortable. Once the PAR groups are formed around specific issues and start generating their own actions to shift specific dynamics that drive WFCL (relationships with employers, access to healthcare, high interest money lending etc.) we will then evolve the evaluation to focus on specific changes (e.g. in working conditions) and emergent outcomes. Following the CA approach, we will refine and evolve the causal theories of change as we contextualise the work and as activities take shape – rather than feel straight jacketed into a design that tries to pre-empt what the relevant key outcomes are. In later phases of the evaluation, methods such as outcome harvesting will enable evaluation of observed changes in specified outcome domains, and process tracing will evidence the causal pathways that enabled them to materialise.

Marina Apgar is and IDS Research Fellow. Mieke Snijder is Postdoctoral Research at IDS. Marina co-convenes the IDS short course Contribution Analysis for Impact Evaluation.