In a rapidly evolving global trade and development landscape, addressing trade-related challenges through aid for trade (AfT) remains highly relevant.

The World Trade Organization–Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development AfT Global Reviews increasingly mention sustainable development priorities. However, the benefits and costs generated by trade on different sectors, locations, and groups (e.g. workers, producers, marginalised, and vulnerable) remain hard to identify and track. To establish how AfT can benefit the poor and disadvantaged, socioeconomic enablers and barriers that affect development impacts must be assessed. This Policy Briefing provides a framing for an inclusive lens on AfT to enable more inclusive policy and programming.

Key messages

- Estimates show that an extra US$1 invested in AfT generates nearly an additional US$8 of exports for all developing countries, but results vary depending on intervention type, income level, and location.

- There is a continuing disconnect between AfT interventions targeting macro trade outcomes and micro-level challenges. For example, trade facilitation programmes may not compensate for local infrastructure issues.

- An inclusive AfT approach should outline how trade benefits disadvantaged groups, disaggregating trade impacts for the poorest, by gender and disability, etc.

- A more inclusive lens on AfT can generate more coherent trade and development policy and programming, enabling trade gains to be shared more equitably for those who risk losing out, such as workers in an industry dwindling due to trade liberalisation.

‘An inclusive aid for trade approach should outline how trade benefits the poor and disadvantaged groups.’

The evidence on aid for trade

Empirical trade and development studies show that providing aid for trade (AfT) can be effective in promoting trade and economic growth in low-income countries (LICs). OECD estimates have shown that an extra US$1 invested in AfT generates nearly an additional US$8 of exports for all developing countries, and US$20 for LICs. However, results vary significantly depending on the type of AfT intervention, the trade constraint and/or sector addressed, the recipient country’s income level, as well as the location.

AfT programmes and interventions typically target four broad areas: trade policy and regulations; trade facilitation such as simplifying burdensome customs procedures; infrastructure for trade such as transport and storage, communications, and energy; and building the productive capacity to improve countries’ export supplies. Our assessment of the evidence across these four areas (Table 1) shows medium to high levels of evidence on AfT for trade infrastructure, trade facilitation, and trade policy and regulations. It also shows recent emerging evidence (low to medium) on export promotion, but with clear gaps in the evidence on building productive capacity to trade.

Table 1: Evidence on aid for trade

| Intervention area | Volume of evidence available |

|---|---|

| Trade policy and regulations | Medium |

| Trade facilitation | High |

| Trade infrastructure | High |

| Building productive capacity to trade | Low to medium |

Source: Authors’ own.

Looking at AfT priorities over the last two decades, AfT interventions focus largely on reducing the time and cost of trade, with the core objective of expanding trade. Priorities in recent WTO–OECD Global Reviews of AfT have increasingly mentioned supporting sustainable development goals. However, the impact of trade beyond its proven aggregate benefits, especially for the poor and disadvantaged, warrants more research to understand the factors that determine their ability to take advantage of positive opportunities or cope with losses that are generated from trade. Especially in the context of low- and middle-income countries, the poorest and most disadvantaged are not a small proportion of the population, e.g. women and young people in precarious work, people with disabilities, and indigenous populations.

Distributional consequences of trade

The benefits of increased trade can be distributed via different transmission channels; for example, through production, labour, and consumption channels. Although it is often hard to identify and track, both the gains and losses from trade tend to concentrate in particular regions (for instance, remote rural areas can face high trade costs due to poor connectivity), sectors, and groups of people.

Global evidence shows that overall trade liberalisation (removal or reduction of trade barriers) can help lift households out of poverty by creating more jobs, benefiting those at the lowest end of the income distribution. However, workers and producers in sectors more exposed to import competition may be made worse off; for instance, if workers lose their jobs or wages fall, or if producers suffer a fall in revenues. The adverse effects can be prolonged over a longer period, particularly for marginalised and vulnerable groups in society, which can increase inequalities.

The trade literature shows that the distributional effects of trade policy reform and/or trade shocks depends heavily on the costs of adjustment (e.g. downsizing or expansion across sectors), and that impacts can differ over time, depending on the speed of the adjustment process. The costs of adjusting are unevenly distributed across people according to their skills and ability to move into other sectors/sub-sectors/industries. Consequently, they can worsen income inequalities.

The effects of trade on development outcomes via consumption (consumers buying and using goods and services) are far less studied. There is a consensus amongst trade scholars that there is an immediate pro-poor impact from trade liberalisation, resulting in cheaper imports and therefore lower retail prices. The poorest households consume mostly tradable goods such as cooking oil and basic textiles as a share of their income, and therefore a small decline in consumer prices can have a larger positive impact on the poor compared to others. On the other side, there is evidence that these consumption gains can be dwarfed by larger, negative income effects on specific groups if there are job losses or effects on small businesses. This leads to net welfare losses mainly for the poorest and most disadvantaged groups.

An inclusive lens on policy and programming

There is a continuing disconnect between AfT interventions targeting more macro trade outcomes and continuing micro-level challenges. For example, those in remote rural areas may not benefit from trade facilitation interventions if they are in areas with poor local infrastructure and, hence, limited connectivity. Many LICs continue to face severe infrastructure deficiencies, such as a lack of connecting roads to main trade centres, which means that the poor and disadvantaged are unable to reap the full benefits of AfT interventions that would otherwise be available. Drawing upon existing frameworks (see Saha 2025), this briefing presents a simple way to consider the impact of AfT on trade and inclusive outcomes.

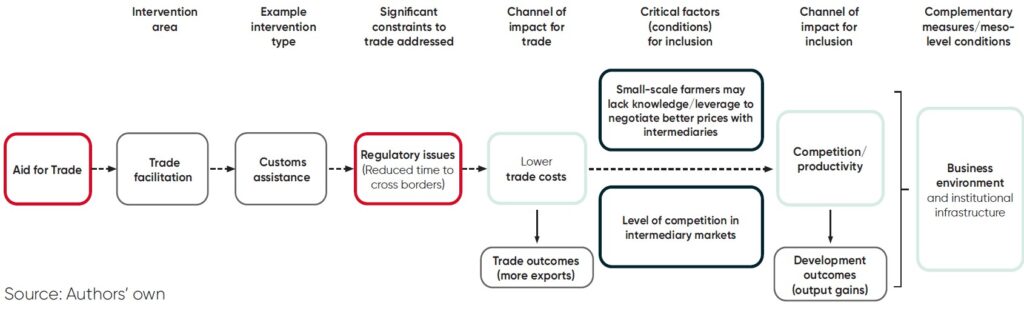

In our framework (see Figure 1, with an example), AfT interventions can expand trade by addressing significant constraints to trade, e.g. those related to the time or cost of trading. However, the impact of this trade expansion on poor and disadvantaged groups depends on certain, critical trade-related micro-level factors or conditions that have attracted attention from various authors (such as labour market flexibility or competition in markets) – which we term as ‘critical factors for inclusion’. These factors relate to poorer groups’ ability to cope with changes or exploit advantages of opportunities from increased trade. In addition, we consider complementary measures as policies at the meso level; for instance, sector-specific and regional policies.

Figure 1: A simple framework and example for inclusive aid for trade

For example, trade facilitation programmes may reduce the time or cost of trading, facilitating increased exports. However, small-scale producers that typically rely on intermediaries for processing/transportation rather than exporting directly may not reap the immediate benefits. The extent to which these savings are passed on along the supply chain to producers depends on their knowledge/leverage to negotiate better prices for their produce and the level of competition in intermediary markets in the existing business environment. Given these complexities, trade facilitation initiatives are more likely to positively impact low-income communities when implemented as part of a broader package of support. This approach can help ensure that more of the benefits reach the poorer in society.

Policy recommendations

Trade impacts can achieve positive impacts for poor and marginalised communities if a more inclusive lens is applied to trade policy and AfT which takes critical factors into account. To achieve this, donors, national governments, and international organisations should consider the following recommendations:

- Ensure that AfT programmes include an assessment of how interventions can impact different groups, including the poor and disadvantaged, identifying the enablers and barriers that shape outcomes across these groups.

- Analyse trade constraints in specific country and sector contexts. AfT programmes should consider the perspectives of different stakeholders; for example, smaller businesses, women-led businesses, firms or workers with disabilities, and ethnic communities.

- Recognise that the impact of trade policy and AfT programmes on trade outcomes varies for different groups, depending on the sector they are involved with, their location, exposure terms of exports and imports, etc.

- Assess how trade-related critical factors for inclusion apply to both firms and households. AfT programmes are often biased towards firm-based or productive outcomes. More effort is needed to measure the effects on households, particularly labour and consumption outcomes.

- Assess any risks for specific groups in advance of trade policy reform and AfT interventions to enable the targeting of support and the design and implementation of complementary measures to reduce the costs and/or improve benefits for the most vulnerable and marginalised groups.

- Collect and analyse data disaggregated by different groups (e.g. gender and disability) and assess impacts over time to inform targeted responses, including both policy reforms and AfT interventions.

Further reading

Engel, J.; Kokas, D.; Lopez-Acevedo, G. and Maliszewska, M. (2021) The Distributional Impacts of Trade: Empirical Innovations, Analytical Tools, and Policy Responses, Washington DC: World Bank (accessed 10 February 2025)

ICAI (2023) UK Aid for Trade, Independent Commission for Aid Impact (accessed 10 February 2025)

McCulloch, N.; Winters, L.A. and Cirera, X. (2001) Trade Liberalization and Poverty: A Handbook, London: Centre for Economic Policy Research

Saha, A.; Abounabhan, M.; Di Ubaldo, M.; Fontana, M. and Winters, L.A. (2022) Inclusive Trade: Four Crucial Aspects, IDS Working Paper 564, Brighton: Institute of Development Studies, DOI: 10.19088/IDS.2022.009 (accessed 3 February 2025)

Credits

This IDS Policy Briefing was written by Amrita Saha (Institute of Development Studies, IDS), Evert-jan Quak (IDS) and Liz Turner (Agulhas Applied Knowledge). It is the result of a collaboration between IDS and Agulhas Applied Knowledge, building on the research on ‘inclusive trade’ at IDS. Underlying research is available on request from the authors. Any views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of IDS or Agulhas Applied Knowledge.

The authors would like to thank Professor L. Alan Winters for his advice.

© Institute of Development Studies 2025. This is an Open Access briefing distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC), which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited, any modifications or adaptations are indicated, and the work is not used for commercial purposes.