Last week, as part of the Global Challenges Research Fund Islands of Innovation in Protracted Crises project, a workshop organised by Professor Jeremy Allouche, Dr. Shilpi Srivastava and Dr. Megan Schmidt-Sane brought together philosophers, sociologists, political scientists, political economists, political ecologists, gender specialists, anthropologists, and development scholars to discuss the notion of the polycrisis.

The concept of the polycrisis refers to a state where multiple crises intertwine, their causes and processes inextricably bound together to create compounded effects. The word polycrisis was popularised by Columbia University academic Adam Tooze, and in early 2023 the World Economic Forum followed suit by warning in its annual Global Risks Report that the world was on the brink of a polycrisis in relation to “shortages in natural resources such as food, water, and metals and minerals.” The concept has since continued to generate more interest, with the Cascade Institute just a few weeks ago creating a new hub for the growing polycrisis community.

This terminology can be seen either as a consequence of the ubiquity and even triviality of crisis, where every ‘problem’ is escalated; or, as an articulation of a fundamentally new reality. Have we entered the age of the polycrisis?

Understanding how crises link together

Undoubtedly, the phrase can help to highlight the complexities we face. Food systems, for example, have been put under severe threat from a number of sources – environmental challenges, conflict and pandemics. Understanding the nature of these separate crises and how they link together may help people understand what action is needed to stop food systems from collapsing.

Polycrisis may also prevent potentially dangerous ‘single crisis’ interventions, where action to address one problem inadvertently leads to another problem due to a lack of understanding of complex connections. Mike Hulme, from Cambridge University, has written convincingly about this challenge with respect to the climate crisis.

The term also helps to show that the whole is more dangerous than the sum of the parts. Thus, the global impact of the conflict in Ukraine was greatly magnified, coming as the world was only slowly emerging from the Covid-19 crisis, and still struggling to cope with the climate crisis.

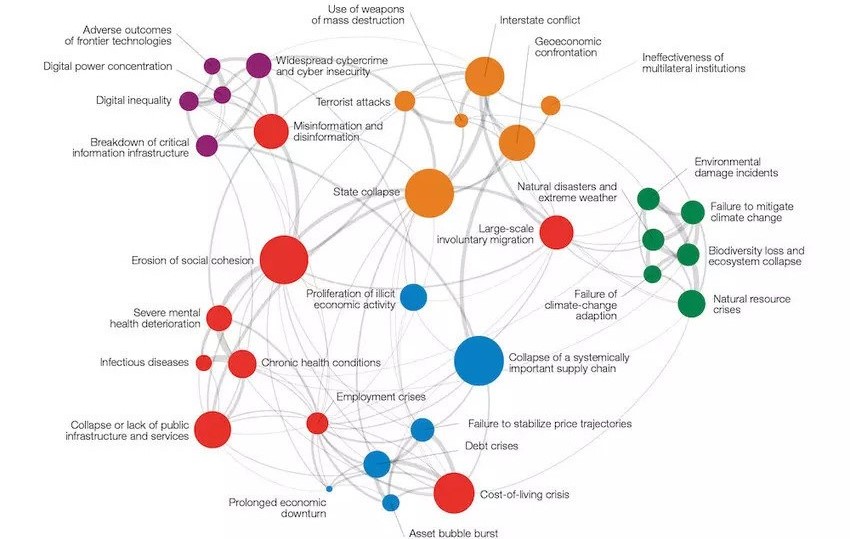

And yet, the very belief that understanding connections between different crises can lead to improved responses can be dangerous. In its Global Risks Report, the World Economic Forum mapped out the connections between risks, and outlined preparedness actions to help mitigate risk exposure. With the right kind of action, the report suggests, crises can be managed on a global scale.

This top-down technocratic approach to managing complex systemic challenges, however, places a lot of trust in governments and large businesses – the very institutions that many believe have been instrumental driving the globalisation and increased consumption that have driven the proliferation of crises. Is it realistic to expect that these institutions can ‘fix’ these crises?

It may not even be desirable to return to business-as-usual. Significant change often emerges through the ruptures produced by crises. Three years ago, there was optimism amongst many that the Covid-19 crisis represented an opportunity for society to think differently – to “Build Back Better”. But that optimism was largely misplaced, as once lockdowns were lifted the world rapidly returned largely to what it had been, with all the talk of new beginnings now a distant memory. What might we have done differently, had we better used the opportunity of the crisis to invent more radical change?

Whose crisis?

The polycrisis narrative also raises questions around whose crises are prioritised. A policymaker in the global North might articulate very different crises from a policymaker in the global South, with implications on how responses are formulated. Meanwhile, for many communities crisis is an everyday reality; people become adept at coping.

The response to the Covid-19 pandemic demonstrates this challenge. Our research has shown that actions to prevent spread of Covid-19 have had a devastating impact on poverty levels in many countries in the global South. This is because the relative risk of the crisis varied from country to country – and whilst lockdowns were an appropriate response in some countries, in others they resulted in children losing years of education. For future pandemics, social and economic development policies need to be crisis-proofed, to protect the needs of those living in poverty.

In times of crisis, we need to look more to communities to develop their own responses according to their own needs and priorities. Our work in food systems, for example, outlines how this might be achieved.

The notion that perhaps humanity cannot ‘solve’ all the crises we currently face can be inherently troubling for those in the global North who have been used to stability and prosperity in the post-world war period. Polycrisis signifies a loss of control. The truth is that we can barely understand the complex things that are happening in the world around us, let alone control them.

For the majority around the world, though, dealing with insurmountable challenges has been part of daily life for centuries. The rain may come, or it may not. What can we learn from communities who are affected by uncertainty?

Our work in coastal areas of Bangladesh and India has explored how transformations can emerge from communities living with constant change. And as a new visual project from IDS shows, pastoralists – people who herd animals over large areas in many different places – are adept at making the most of uncertainty, and we can learn much from their way of life.