The introduction of ‘digital-by-default’ welfare and social protection systems in the UK and beyond has delivered efficiencies and cost savings for governments and can be convenient for recipients.

But, given the rapid pace of change, we need to understand the ethical, social, and political implications of digital welfare from the perspectives of the poorest and most marginalised members of our societies. In the face of a growing body of research on these communities’ challenges in accessing their entitlements, this briefing looks at what a ‘good’ digital welfare state might look like. Our research shows the need for systems which are designed to treat people with care and dignity, inclusivity, adaptiveness, and transparency. Digital welfare systems need to work for the hardest to reach first. In the words of a workshop participant: ‘a good service makes you feel trust in the service itself, the platform, and the government’.

Key messages

- The views of welfare recipients are rarely included in the design of digital welfare solutions; they do not get the space to engage in a public debate where they can scrutinise and deliberate on them. We need more ways to include these voices and to learn from them what ‘good’ might look like.

- These considerations do not just apply in Europe; as social protection systems are digitised around the world, governments need to engage with citizens to ensure systems are built to meet the needs of the most socially marginalised communities who are less likely to have the digital access and skills necessary to engage with digital services.

- Digital welfare platforms in the UK and Scandinavia offer improved internal operations but can seem exclusionary and opaque to those accessing them to claim their right to social assistance. These systems need changes underpinned by a commitment to ensuring that the broader digital welfare ecosystem works to deliver entitlements to those in need with dignity and respect.

Digital welfare systems need to work for the hardest to reach first, treating users with patience, compassion, and respect.

The right to social security was recognised in the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is embedded in international human rights law. However, as welfare systems are digitised, this right is under threat both from unaccountable algorithmic decision-making and from digitally excluded communities’ lack of access to services. We ran two workshops to explore this issue and to understand what a ‘good’ digitised welfare system might look like: one with community groups supporting welfare recipients in Brighton, UK, and one with experts on digital welfare from Norway, Sweden, and the UK.

Good digital welfare services should prioritise human dignity, inclusivity, and accessibility, offering diverse channels for delivery and redress.

Digitisation of social security systems: new exclusions

The digitisation of social security systems is a key area in which citizens’ relationships with the state has been reconfigured by digital technologies, not only in the delivery of welfare payments (for example, Universal Credit in the UK) but also in automated decisions about eligibility and payments. Digital-by-default or ‘digital-first’ strategies can lead to people with limited digital access or skills struggling to apply for, or access, their entitlements. Whilst there is consensus that providing access to physical, in-person services is vital to ensure inclusion, governments and municipalities often make it challenging to access offline alternatives. In Norway, for example, it is still possible to apply on paper, but these options are hidden on websites.

Many people may rely on intermediaries to access digital welfare – including friends and family, community-based organisations or librarians – and might experience additional vulnerabilities in these dependent relationships. Migrants and linguistic minorities often struggle with websites and platforms not provided in a language they are able to read and interact with fluently. If welfare claimants do not fully understand the interface or the language being used, they may inadvertently input wrong information and then face serious consequences resulting from this.

Digital-by-default or ‘digital-first’ strategies can lead to people with limited digital access or skills struggling to apply for, or access, their entitlements.

Transparency and accountability for citizens

Digitisation has often been accompanied by challenges in seeking recourse for inaccurate decisions. It is often difficult to reach a human who can take claimants’ circumstances into account and who can embody compassion and empathy in decision-making. In the Norwegian Social Security scandal, known as the NAV scandal in Norway, at least 48 people were wrongly convicted of social security fraud, with some receiving prison sentences. In many instances, including in Uganda, South Africa, Brazil, and other countries, the only viable option for citizens to seek recourse is by taking their claim to court. In many countries, citizens are automatically cut off from welfare if an algorithm predicts the person to be a fraud risk or ‘undeserving’. In the UK, people are ‘sanctioned’ and can have payments stopped or reduced if they miss meetings or do not comply with certain commitments. In many contexts, citizens struggle to correct inaccuracies in data or challenge decisions.

Digitisation is thus seen as a way of streamlining these processes and providing greater surveillance capabilities to ensure beneficiaries are meeting conditionalities and taking steps to join the workforce. In countries such as Denmark and Norway, there are explicit policy commitments to ensuring individual dignity in digitised government systems, but these are undermined by the misuse of individual data which appears to be driven by an interest in predicting and controlling citizens’ behaviour.

What does good look like?

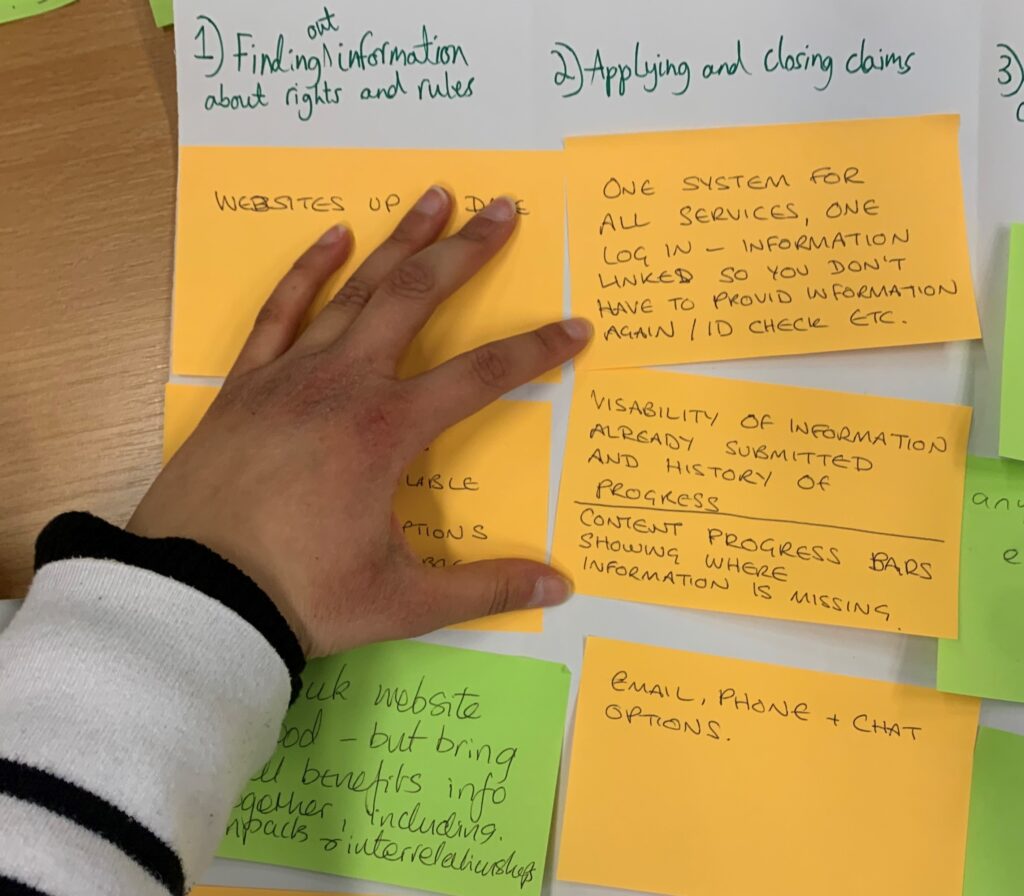

In our workshop with people supporting welfare claimants in Brighton, we asked participants about the issues the communities they worked with faced during three stages of the digital processes involved in applying for welfare payment:

- Finding out information about what you are entitled to;

- Applying for payments; and

- Making changes to your claim.

The issues they raised were particularly severe for digitally excluded communities, who are often those most reliant on the state for support. This included a lack of clarity about offline access options, a feeling that people had ‘multiple hoops to jump through’, and the challenges with two-step, mobile-based verification for people who either did not have a phone or who changed numbers frequently. There was a strong feeling that information flows were one way: that claimants were obliged to provide lots of information but that the information did not flow back in the same way. Workshop participants made the following practical suggestions about how the systems might be improved.

Finding out information about your entitlements

- Digital welfare systems should have the user friendliness of big commercial websites such as Amazon;

- Video tutorial options for all tasks;

- Clear headings and sub-headings;

- Experts to talk to about entitlements, rights, and rules; and

- Websites with translation options for multiple languages.

Applying and closing claims

- Save options – being able to save and continue claims;

- Content progress bars showing where information is missing;

- Easy eligibility checklist;

- Forms in simpler language; one question at a time; containing examples; and using formatting that is accessible; and

- One log-in – all information linked so you do not have to provide information again.

Updates and changes to your claim

- Notifications via Short Message Service (SMS) or WhatsApp;

- Alerts, rather than having to log on to find out that you have been sanctioned (having money taken from your payments);

- Help people to claim, not to discourage claims;

- Have access to telephone logs and records of conversations online.

Whilst these might seem like superficial changes to the way that platforms work, these suggestions reflect the fact that digital platforms are manifestations of a set of political decisions about information and power. When governments and the technologists that work for them make choices about how information flows between governments and citizens, they are making political choices about the rights and responsibilities of both parties.

A ‘good’ digital welfare state will therefore be reflected in the design of the platforms. They should be designed with respect for human dignity and agency, inclusivity and accessibility, and by features such as multiple – digital and offline – channels for service delivery and recourse, and open and accountable systems and partnerships.

Policy recommendations

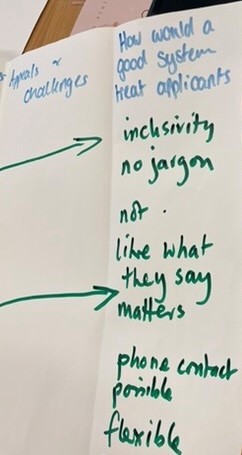

In the UK, the design of Government Digital Services is shaped by the Government Design Principles, which provide a firm grounding for well-designed, user-centric services. Beyond these design principles, our workshop participants had strong suggestions about what the experience of using a ‘good’ digital welfare system might be like for citizens. This can be summed up in the words of one participant: ‘A good system treats applicants like what they say matters.’ Four aspects are key:

Care and dignity

- Systems that are responsive to the needs of victims of trauma by having ‘a human in the loop’ – with trained staff and an attitude of providing active help, support, information, and compassion.

- Access to a person who is an expert to talk to about your rights and the rules of the welfare system.

Inclusivity

- Systems which are genuinely accessible to all members of the community, and which ease the burden of compliance and do not increase stress. People want online forms that consider that people take in information in different ways.

Adaptiveness

- The state should understand and respond to the variety of needs that citizens have when interacting with digital welfare systems, and provide services accordingly. Adaptive and flexible systems should be provided which are not about ticking a box but which are responsive to peoples’ life stories and evolving circumstances in a seamless and proactive fashion (described in Norwegian as helhetlig). This means hearing someone’s life story and the complexities in their lives and seeing how the state can respond to their needs; this is especially important for victims of violence.

Transparency

- Making sure citizens have the right level of information provision without increasing their administrative and psychological burdens.

- Systems of recourse should be readily available in offline and online channels. This transparency and accessibility should extend to systems of predictive analytics and automated decision-making in welfare systems; these should not be ‘black-boxed’ but should be open to public scrutiny.

- Overall, the focus of the state should be on ensuring that those in need get access to their entitlements.

Further reading

Alston, P. (2019) Report of the Special Rapporteur on Extreme Poverty and Human Rights: Digital Welfare State, 74th Session Agenda Item 70 (b), New York NY: United Nations General Assembly (accessed 10 December 2024)

Mears, R. and Howes, S. (2023) You Reap What You Code: Universal Credit, Digitalisation and the Rule of Law, London: Child Poverty Action Group (accessed 10 December 2024)

UK Government (2024) Government Design Principles (accessed 10 December 2024)

Verdin, R.; O’Reilly, J. and McDonnell, A. (2023) Digital Welfare Ecosystems in Europe: Social Protection Systems Preventing Social Exclusion and Enhancing Opportunities to Participate in the Digital Economy, EUROSHIP Working Paper 23, Oslo: Oslo Metropolitan University (accessed 10 December 2024)

Credits

This IDS Policy Briefing was written by Becky Faith (IDS) and Kevin Hernandez (Universal Postal Union). The research was funded by the ESRC Digital Good Network through the University of Sheffield (grant reference ES/X502352/1). Any views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of ESRC or IDS.

With thanks to Lihi Shefer (IDS), Cathy Urquhart (Manchester Metropolitan University/University of Lund), Anna Dolphin (AbilityNet), the Brighton and Hove Digital Inclusion Network, Miranda Kajtazi (University of Lund), and Øystein Sæbø, Sara Hofmann, Ida Heggertveit and Hanne Rydén (University of Agder).

© Institute of Development Studies 2024. This is an Open Access briefing distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence (CC BY), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original authors and source are credited and any modifications or adaptations are indicated.

ISSN 1479-974X