Ending hunger and securing food for all is one of the crucial United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). But food security entails sustainable and sufficient production, equitable distribution and efficient consumption of nutritious food. This implies that a flourishing agriculture sector is vital for achieving the goal of a hunger-free world.

Data indicates that around 75 per cent of farmers in sub-Saharan Africa and Asia are smallholders and majority of them are poor. Also, due to high transaction costs involved in dealing with them, many small farmers are excluded from remunerative global value chains. Hence, they lack opportunities to improve economic returns and they remain trapped in vicious cycle of poverty. Consequently, it affects the production and distribution of healthy food. A hunger free world therefore requires strategies to bring small farmers out of poverty.

Are farmer cooperatives a panacea?

Policymakers throughout the world are emphasising the importance of ‘farmer cooperatives’ as a strategy to include smallholders in agricultural value chains and to enhance their incomes. For instance, when small farmers in a region of Central America were collectivised to reduce transaction costs, retail companies preferred direct partnerships with these groups to better control production processes and to ensure compliance with the quality norms in international markets. These partnerships benefitted farmers in the region. The success of this programme inspired the Indian government to establish legal and institutional frameworks for nurturing ‘farmer producer companies’ (FPCs). So, it amended The Company Act’ 1956 in 2002 and formulated institutions such as the Small Farmer’s Agribusiness Consortium (SFAC) and NABKISAN finance ltd. The Indian government plans to promote 5000 FPCs involving millions of small farmers with the expectation that farmers will be in control of their own destiny.

However, smallholders who are bound together and expected to perform complex business activities face significant challenges. The famous institutional economist M. Olsen propounded in his work The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups way back in 1965, voluntary group activities seldom lead to benefits for all members, even when individual and group interests merge together. In addition, socio-economic differences and mutual distrust amongst members can result in groups suffering internal pressures and conflicts when they perform business activities.

Moreover, modern day markets are becoming too complex to decipher for poor smallholders. A good example of this is the headline-grabbing rise and fall of India’s guar crop value during America’s shale gas boom. Guar gum is used in fracking, a method of extracting shale gas. During America’s shale gas revolution (2011-12) demand for guar gum led to a ten-fold price increase in the crop, bringing riches to India’s smallholders. But as crop prices rose, the gas industry sought a lower cost synthetic substitute and once found, guar crop prices fell sharply to their normal level. Very few experts could have anticipated the cross-linkages between the petroleum sector and crop prices. Such complex price variations in different markets have enormous impact over poor smallholders. Along with price fluctuations, issues such as global warming and frequent weather extremities create uncertainty for FPCs.

How do farmer groups deal with uncertainties?

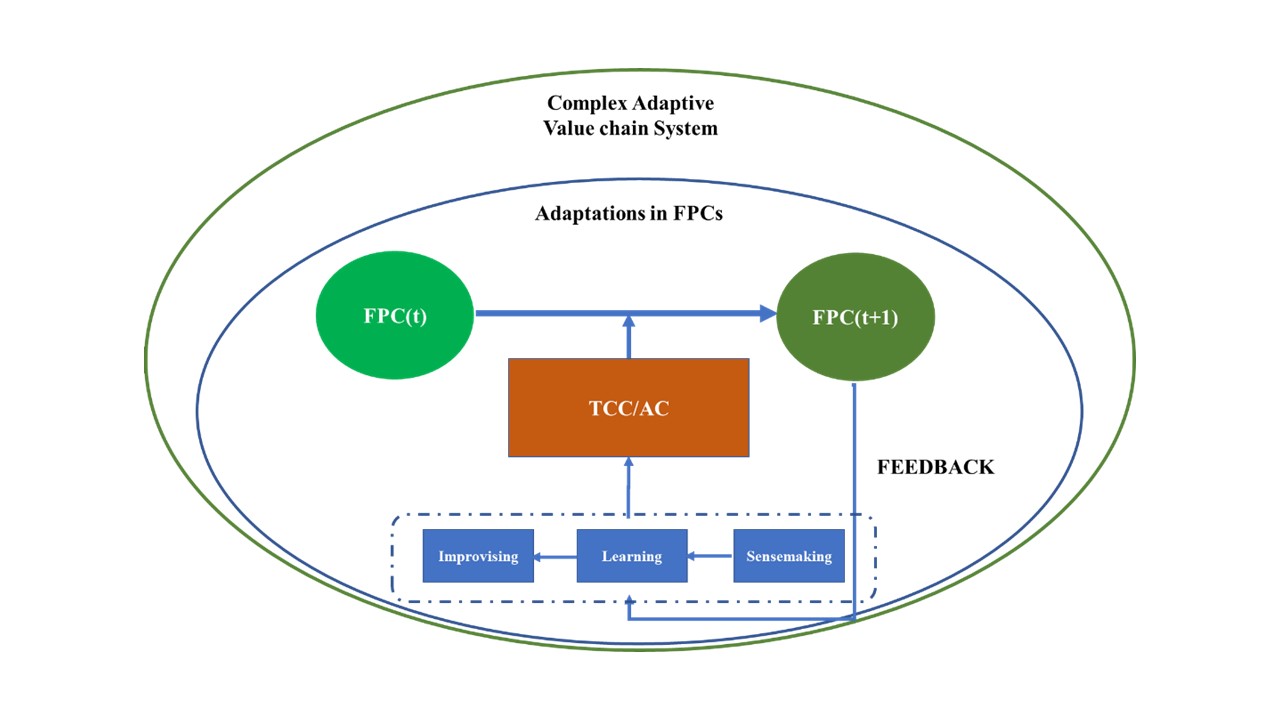

During this summer, I conducted research to analyse how FPCs manage complexities embedded in value chains and arrive at business-related decision collectively. I studied cases in four regions of India: Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh and Telangana, that are dealing with different commodities. Analysis showed that successful cooperatives ‘adapt’ to win the contingencies. When the company management ‘sense’ the risks and opportunities; when they ‘learn’ different approaches; and when they ‘improvise’ based on their experiential learning, FPCs emerge as successful to earn profits.

For instance, in one of the FPCs I studied, the management sensed the decreasing average prices of Soybean in the domestic markets; they learnt about quality norms prevalent in international markets; and improvised production processes to comply with the standards. Thereby, they secured greater returns during the subsequent year.

The research findings highlighted how the ‘adaptive capacity’ of FPCs depends on leadership, financial saving capabilities and internal communication strategy. With higher adaptive capacities, smallholders better withstand both internal and external uncertainties.

Embedded optimism in research finding

To maximise the effectiveness of FPCs, implementing governments/actors should help build the adaptive capacity of farmer groups. Through a well-designed training programme, it is possible to expose group leaders to the uncertainties of the business environment, wherein they can learn the approach for sensing-learning and improvising. Further, governments can facilitate connections between diverse stakeholders, which would enable farmer groups to build networks. Most importantly, the credit-giving authorities can devise better models to measure adaptive capacities of farmer groups, to offer differential/lenient treatment to strong FPCs while offering them loans.

I firmly believe, a strategy of promoting adaptable farmer groups is a promising way to improve farmer incomes. It can also help in harnessing the potential of remote areas to boost global food production and to secure food for all.

Rohan S. Katepallewar is an engineer turned social scientist, and a recent graduate of IDS with an MA in Globalisation, Business and Development. He has worked as a Prime Minister’s Rural Development Fellow in India to promote livelihood security through value-chain development in tribal-conflict prone areas of central regions. As a state project manager, he promoted FPCs and through his experiences he felt the need for deeper analysis of the idea of farmer companies.