A recent workshop in Nairobi, Kenya, co-hosted by the Institute of Development Studies and the Centre for Human Rights and Policy Studies (CHRIPS) provided an opportunity for reflection and discussion on the potential opportunities, and practical limitations, of using digital technology to promote peace, monitor violence, and support early warning and crisis response in the run-up to Kenya’s August 2017 elections. The workshop brought together practitioners, policymakers and researchers involved in preventing, monitoring and responding to violence at this critical period in Kenyan politics.

Monitoring, early warning and response

Monitoring systems can play a vital role in reducing, preventing and responding to violence. Effective early warning and crisis response depends on the availability of timely, reliable data, in order to react quickly, determine the scale and dimensions of crises, and target responses accordingly. Data can come from ‘old’ media such as newspapers or radio reports, or ‘new’ social media, digital platforms, and other crowdsourcing systems, which have proliferated in Kenya since the height of election-related violence in 2007/08.

Research highlights significant media biases in selection and coverage of conventional media reporting on violence and insecurity, while technology gaps within and across individuals and groups can determine whose voices are amplified by social media and crowdsourced data. Together, these feed concerns that both traditional media and digital platforms do not equally reflect the experiences of the most vulnerable, who are often key populations in early warning and crisis response.

While each reporting pathway can provide critical information for responders, practitioners and policymakers, there is limited robust research on their comparative reliability and comprehensiveness. An ESRC-funded project on New and Emerging Forms of Data for Crisis Response, by IDS with the University of Sussex, has supported research into the comparative differences between ‘old’ media reports of violence, and those collected through ‘new’ crowdsourced social media and digital platforms.

In the course of the Nairobi workshop, two key differences between conventional media and new digital technology reporting were identified, both pointing to new possibilities for practical crisis response, policy and research in this field.

Timeliness and duration of coverage

The timeliness of violence reporting is an essential factor for first responders, practitioners and policymakers seeking to prevent, reduce or de-escalate incidents of violence. IDS and Sussex researchers compared media reports of violence during Kenya’s last election in 2013, collected through the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED), with crowdsourced reports generated by individuals through Ushahidi’s 2013 election monitoring platform, Uchaguzi. While the 2013 elections witnessed significantly lower violence than the 2007/08 post-election violence crisis, nevertheless, insecurity affected populations across the country, and the timeliness of that reporting can illustrate key opportunities and limitations of different reporting systems.

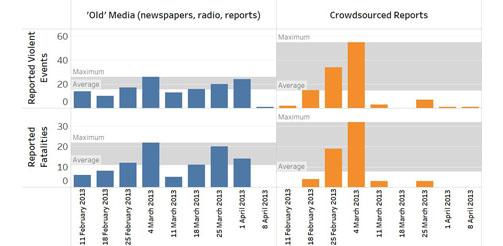

The research found that while the incidents reported through digital crowdsourced platforms peaked in the run-up to and on the day of elections themselves, media-based reporting was more constant over time, particularly in its coverage of post-election insecurity (see Figure 1). This suggests that social media and custom digital reporting platforms are not used as extensively in the wake of elections, and that periods of high public attention may influence the way in which these platforms are used to report insecurity. This post-crisis period can often be accompanied by sporadic, but nevertheless significant, levels of violence that policymakers and responders often need to document and react to, if they want to ensure full and timely support is given to affected populations.

Figure 1: Reported Violent Events and Fatalities by Source Type, Kenya, 12 February – 13 April 2013

These findings suggest a complex picture of the timeliness of different reporting pathways: while social media and digital platform reports are certainly quicker at conveying information at the peak of crises, they may not provide as accurate a picture of insecurity over the entire period of instability. As a result, policymakers and responders may need to adjust their strategies to complement crowdsourcing systems with alternative reporting processes in the wake of insecurity.

The geography of violence risk

The geography of violence is also an important consideration in response. Different sources of reporting can generate divergent pictures of where violence occurs, where it is concentrated, and where it spreads during a crisis. In the same comparison of 2013 data, researchers found that media reports of violence were more evenly spread throughout Kenya, with incidents of violence documented in 34 of Kenya’s 47 counties. By contrast, digitally crowdsourced reports were collected from 28 counties, and almost half (40.1 per cent) of these were concentrated in the capital, Nairobi (see Figure 2). A systematic analysis of the characteristics of areas in which violence was reported by both sources found that crowdsourced reporting is typically concentrated in areas with higher infrastructural development (proxied by the concentration of nightlights), GDP per capita, access to mineral resources, and population density.

Figure 2: Location and Number of Reported Violent Events by Source Type, Kenya, 12 February – 13 April 2013.

Together, this suggests that crowdsourced systems are most effective when they are capturing reports of violence in wealthier, urban areas with better access to internet and communication infrastructure, but may miss reports of violence in more remote areas where access to information communication technology is more limited. Monitoring, understanding and responding to crises in both contexts is of fundamental importance for early warning and crisis response systems, in order to ensure that vulnerable populations in already marginalised areas are not further neglected.

Going forward

The findings suggest that there are significant differences in the timing and geography of violence as captured by crowdsourced digital systems, compared to ‘old’ media. In the next phase of the research, the project will seek to expand its analysis of violence reporting in the upcoming Kenyan elections of August 2017, in order to test whether the same structural factors also affect present-day reporting patterns. Print media itself is also characterised by biases that may shape the way violence is reported and acted upon. A further aspect of the project will seek to integrate reports from partner networks of crisis responders on the ground to compare their accounts of insecurity with those captured by social media and print media, to further inform how policymakers, practitioners and researchers can best track, respond to, and reduce violence in crises.

Image: ‘A dispute arises outside a polling station in the Kibera slums, Nairobi’. Credit: Panos / Sven Torfinn