Scientists say we are living in an age of mass extinction with on average the abundance of native species in most major land-based habitats has fallen by at least 20 per cent in the past 100 years. With COP15, also known as the United Nations Biodiversity Conference, now in full swing, the conference aims to bring together countries to agree on targets to ensure the survival of species and stem the collapse of ecosystems across the world. Due to the disruption of the Covid-19 pandemic, this round of negotiations has been delayed for several years. This means that there is ever more importance placed on COP15 to halt the destruction to the natural world.

Lars Otto Naess, IDS Research Fellow, said of COP15:

“In view of the planet’s future, the biodiversity COP15 is as important as the climate COP27, yet COP15 hasn’t received anywhere near the international attention it deserves. Biodiversity loss and climate change share many of the same root causes, and they need to be addressed together, through similar urgent and systemic changes.”

At COP15 negotiators from 164 countries are meeting to thrash out the post-2020 global biodiversity framework – often referred to as the “Paris Agreement for nature”. The last time the international community set decadal goals for biodiversity was in Japan in 2010. In September 2020, a on progress towards the Aichi Biodiversity Targets found that governments had collectively failed to meet even one of these targets. This is the reason why this COP15 is so important: the outcome will have wide-reaching ramifications for our planet’s biodiversity, including for us people.

However, using the social monitoring platform Meltwater, we undertook analysis of the global Twitter mentions of #COP15 and compared them to the mentions of #COP27 (the 27th United Nations Climate Change conference) from between 1 January and 17 November 2022. that very few people are engaging in conversations about COP15 in online spaces, and that major voices who often give the spotlight to environmental issues are missing when it comes to ongoing biodiversity loss and degradation.

This is worrying given that previous targets set at COP10 in Aichi, Japan, have not been reached. Although only a snapshot of public sentiment, it indicates there should now be a renewed urgency to press decision makers to act to stem the loss of biodiversity around the world.

What does the data show?

We found that COP27 has been mentioned more than 21 times ( since. Translating to 110 times (11,610 per cent) more impressions (total number of followers who follow these accounts) and more than six times (617 per cent) greater reach (number of unique people who have seen the content). What we can discern from this data is that while COP27 has been mentioned much more than COP15, there is a much smaller difference in the reach number. This infers that COP15 has been talked about by far fewer but by more prominent accounts that have a greater reach.

Graphic showing number of impressions (number of people who have seen the post) between 1 Jan to 17 Nov 2022.

First spike – 10 May, UN talks to tackle desertification and land degradation in Ivory Coast.

Second spike – 16 June, announcement of COP15 will take place in Montreal, Canada.

Third spike – 21 Sep, announcement by UNGA of a new commitment to biodiversity.

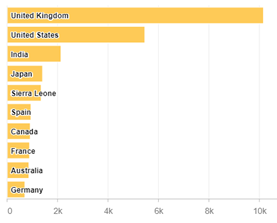

Below is a chart showing which countries are talking about COP15 the most.

From the same data we can see that the top five countries from the Global South are: India, Sierra Leone, Columbia, Brazil and Mexico. These are all places that are experiencing biodiversity loss at an accelerated rate.

Whose voice is missing?

Looking at the data we can see that while COP15 and the issues around biodiversity are being talked about, it is often by prominent Global North voices. Of the top 50 Twitter posts by engagement that mention COP15 only one was registered to an account from the Global South. The most engaged with Twitter post that mentions COP15 was from the MP for Brighton, Pavilion Carline Lucas.

Biodiversity degradation and the threats to global ecosystems are complex issues that are unlikely to be solved by easy one step solutions, rather ongoing conversation and input from multiple sources. Marginalised communities who are most often facing the brunt the impact of climate change and biodiversity loss seem to be largely missing from the global online conversation on action to protect biodiversity.

Further analysis shows that, of 50 posts on COP15 with most engagement, none come from accounts that were run by indigenous, first nation persons, groups or tribes. Whilst it might be true that many of these groups are not online, this does serve to show that the global online debate around biodiversity is unrepresentative and attention is skewed towards decision makers in the Global South.

The COP15 conference continues until 19 December, and we wait to see the agreement that is reached, and if it works for both nature and people.