In 2020 Donald Trump was reportedly the biggest source of political disinformation in the world, fuelling social unrest, voter supression, and distrust in democracy. The US election forced us to stare over the precipice at what happens if the political deployment of digital disinformation is allowed to go unchecked. This moment must serve as a wake-up call about the threat to the democratic progress of unregulated political speech amplified by Big Tech (including Facebook, Twitter and YouTube) and mainstream media.

Trump’s team of election strategy consultants, data analysts, ‘meme’ manufacturers, trolls and bots controlled from within the White House, or other similar teams, will likely now move on to manipulate the democratic process in other countries scheduled to hold elections in 2021. In both authoritarian states and liberal democracies, politicians will spend billions hiring similar teams to psychologically profile citizens and micro-target them on Facebook, Twitter and YouTube with the aim of manipulating beliefs and voting behaviour. Addressing this digital colonisation of the political sphere by Big Tech platforms is an urgent global problem for democracy. A new US President provides a much-needed opportunity to impose radical reform of social media companies and political engagement.

The disinformation machine

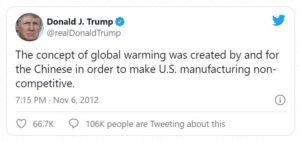

Recent elections have shown vividly how online disinformation and baseless conspiracy theories are being deployed to derail democratic deliberation, dialogue, and debate. Since the UK’s Brexit referendum and the first Trump campaign in 2016 politicians have developed increasingly sophisticated disinformation machines across multiple media with the aim of disrupting, distorting and drowning-out democratic dialogue and debate. In many instances, they’ve sought to replace discussion with vile vitriol, attacking women , presenting ethnic minorities as the enemy, and presenting white male populist candidates as the solution.

In the US, we’ve seen mainstream media benefit from amplifying Trump’s highly inflammatory rhetoric gaining financially from the increased website traffic and advertising spend that it generates for them. It was interesting that, when it became clear that Trump would lose the 2020 US election, and that Biden would imminently assume control of media regulation, social media sites started blocking Trump lies. At that point, mainstream media outlets that had uncritically amplified his messages in the past, started qualifying Trump claims as “unproven” or “baseless” in their reports.

To understand how to pull back from the precipice we now need to go beyond the simplistic characterisation of Trump as a one-man Twitter madman. We need to understand the sophisticated data-analysis and disinformation machine in the White House that used Black voter suppression and false border wall pledge to engineer his surprise victory in 2016. Trump has been at the centre of a dense network of disinformation making astute use of the affordances of Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and other platforms to propagate fear and hate, fuelled by lies and conspiracy theories, to mobilise misogyny, militias and disinformation. We have learned that fake news travels six times faster on Twitter than the truth, so attracts more advertising revenue. Facebook, Twitter and YouTube have made billions in profits from the hate-filled social media traffic generated by right-wing conspiracy theorists, white supremacist and misogynist groups allied to Trump. Sensationalist lies are good for (social) media businesses, irrespective of the cost to Black Lives, democracy or sustainable development.

Big Tech monopolies

Since Brexit and Trump, the use of political polemics and digital disinformation has inflicted great damage to democratic dialogue and peaceful political process. However much of the foundational damage was done before Cambridge Analytica weaponised digital disinformation: marginalised populations had felt unheard and unrepresented by political parties captured by corporate and establishment interests. It is their discontent that was mobilised to support candidates claiming to be anti-establishment.

The events of the past highlight that the power of Big Tech monopolies must be curtailed along with their influence over political process. Media regulation, including social media regulation needs to ensure that political lies, misogyny and race hate are outlawed and that powerful disincentives are put in place for politicians and media companies that profit from it. The ability to block Trump lies in the days following the election show that it was possible all along, just not profitable.

Breaking up the tech monopolies, as former Presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren had pledged to do, taking down hate speech and political lies, and the banning and prosecution of its authors is a logical technical response and a very good place to begin. However, these technical fixes do nothing to address the underlying issues of economic inequality and gender and racial under-representation that create political disaffection, distrust, and detachment from the political process. Trump, Bolsonaro, Modi and Farage are the symptoms not the cause of this problem. Citizens’ interests are served by an increase in representatives that look and sound like them and who commit to remove the injustices that they experience. This is the agenda of groups including Justice Democrats.

Digital technnology and political participation

Instead of using social media to profile and micro-target voters, digital technology could be used as part of authentic democratic listening to understand why tens of millions of citizens distrust politicians who often seem more attentive to powerful corporate and lobby interests rather than to voters. Digital media has been used by citizens to collectively re-write their constitution and to co-determine government policies and to track and monitor government spending. We could and should break up the damaging global dominance of Big Tech monopolies or nationalise them as Nick Snricek has argued. Political advertising could be banned on social media or transparently regulated. Political lies could be prohibited and punished as could their uncritical reproduction by (social) media companies. The political will to do this has been largely missing until now.

Understanding influence and finding solutions

Part of the problem has been that incumbent Presidents and Prime Ministers have owed their political position and power in part to media companies including Facebook, Twitter and YouTube. Now that Trump has been unseated there is a window of opportunity to remove the insidious influence of Big Tech over democratic dialogue and deliberation.

We urgently need more research – especially in emerging economies where democratic protections are particularly weak – to understand how the disinformation machine works in emerging economies, such as that from the African Digital Rights Network. Critically we need to identify political solutions to the underlying causes of disaffection and distrust in politicians. Technical and regulatory actions are important and necessary, but they are insufficient, sticking plaster solutions, unless the underlying political and economic problems are also addressed.

Tony Roberts is a Digital Development Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies and is the principle investigator of the African Digital Rights Network – a diverse group of activists, analysts and academics working in ten different African countries –investigating the use of digital disinformation to disrupt and distort governance processes.