The Covid-19 outbreak currently devastating India meant that the UK Prime Minister’s intended visit this month had to be cancelled, and for now it appears the trade talks will be on hold, while the immediate crisis rightly takes priority.

However, longer-term, the two countries’ ‘Enhanced Trade Partnership’ (ETP) will remain at the centre of attention as a roadmap to a potential Free Trade Agreement (FTA).

As the UK tilts its foreign policy towards the Indo-Pacific region, India is undoubtedly viewed as a key strategic partner but despite the potential for both countries to gain from deeper economic cooperation, the road towards a UK-India FTA is not straightforward.

In this first of two blogs, we discuss some of the distinct bilateral characteristics that set the UK-India negotiations apart from the usual trade talks. These include rising trade and the promise for quick wins and the huge potential in services. In the second blog, we will examine the strong business-to-business links, important geopolitical factors (including collaboration on vaccine provision), and the potential for development gains.

Rising UK-India Trade

Bilateral flows between both partners in goods trade, services trade, and investment are substantial, especially in the latter two dimensions. In 2019, the UK shipped £4.8 billion worth of goods to India and nearly £3 billion in services. Conversely, the UK imported £8.4 billion worth of goods and £7.3 billion worth of services. Further, the UK stands as the sixth-largest investor in the Indian economy, with a cumulative estimated flow of about 6% of the total FDI into India, while India is the second-largest investor in the UK.

Goods and services trade have moved on different trajectories, though. We will first discuss services trade, which is an area of particular strength for both countries. Then we turn to goods trade where, in contrast to services, India’s share in UK imports has fallen during the period 2013-16, which may be linked to the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) import regime, whose (imperfect) features we discuss in some detail below. Thirdly, we broaden the picture to include investment links and wider geopolitical considerations.

Growing dynamism in services

What really stands out in UK-India trade is the deep and growing relationship in cross-border services trade. First, consider the significance of services trade relative to conventional goods trade. In the UK-India context, services constitute about 40% of the total value of bilateral exports and imports.

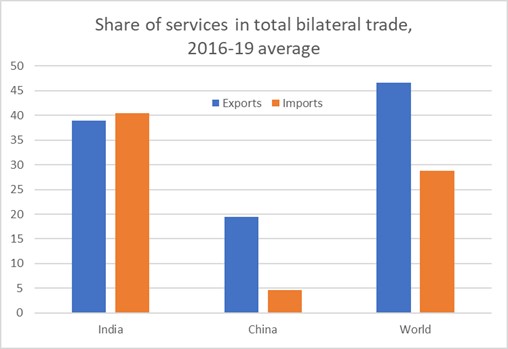

This extraordinarily high figure resembles that of the UK’s overall services share in its total trade with the world, which is driven to a considerable extent by proximate EU markets and the United States. Given that India is a faraway emerging economy, this similarity is remarkable and is testimony of the high revealed comparative advantage that both partners have in specific areas of services trade. The UK’s special relationship with India is also evident when comparing the services share with China as a comparator (Figure 1).

Figure 1: UK services: shares for India, China and the World

Source: Authors’ calculations on the basis of ONS Pink Book 2020 statistics.

Second, UK services imports from India are growing buoyantly, with the import share of services rising from 37.5% in 2016 to 47.8% in 2019. In that regard, India is very different to China, or indeed the World, for which services import shares have been stable and much lower than the export share.

The driving force behind this increase is ‘Other business services’, a group of potentially high-skill intensive services encompassing management consulting, professional and technical services, UK imports of which went from £1.9 billion in 2016 to £4.3 billion in 2019. This rise nearly doubled India’s share as a source country in this category. (It is worth noting that within ‘other business services’, it is services trade between affiliated enterprises and intragroup fees that have grown considerably. This reflects the strong position of inward investment that Indian enterprises hold in the UK. At the same time, charges for IPR are much higher on the export side, i.e. the UK is exporting intellectual property to India, which will be sustained and incentivised only by meaningful protection of property rights and investment.)

GSP and trade in goods

Trade in goods between the UK and India has been less dynamic than services trade. A primary conduit for Indian exports to the UK market currently is the UK’s GSP regime, which applies since January 2021. Designed on the basis of the EU GSP, it is a unilateral scheme offering lower than Most Favoured Nation tariffs on imports from India. The GSP is of great relevance for Indian exporters: over the last decade more than half of UK imports from India (in value) used GSP preferences (Figure 2), which is remarkable considering that only about 66% of the tariff lines are eligible for the scheme.

Figure 2: UK imports from India by preference regime

Source: Author’s calculations using data from EU Comext

The GSP scheme has several shortcomings, however. Other than it being unilateral, and applying to goods trade only, it offers preferences whose coverage and depth have been decided by the donor country (originally the EU). Furthermore, GSP preferences are periodically withdrawn in certain sectors from countries that become internationally competitive, through so-called graduations.

Over the period 2014-2017, over 15% of UK imports from India could not benefit from preferential tariffs because of GSP graduations. The GSP remains an imperfect system, and the transition to a bilateral FTA, conferring more long-term certainty and encompassing also services, will be welcome.

In part two of this blog we will examine the strong business-to-business links, important geopolitical factors, and the potential for development gains. This is part of a new three-year project Unlocking the Potential for Future India-UK Trade and Development, which aims to understand the key factors that stimulate or hamper trade relations between the UK and India through analysis at various levels. In particular, the transition from the GSP to an FTA and the dynamism for services trade, but also on the likely effects on development outcomes – skills, jobs, and poverty, focusing on mutually beneficial partnerships for effective development.

Ingo Borchert is a Senior Lecturer at the University of Sussex Business School and Deputy Director of the UK Trade Policy Observatory. Mattia Di Ubaldo is a Research Fellow at the University of Sussex Business School and a fellow of the UK Trade Policy Observatory.

This blog is part of our blog series ‘Voices on Inclusive Trade’. Other blogs in this series:

- Can inclusive trade policy tackle multiple global challenges?

- Pathway to UK-India Free Trade Agreement: call for focused advocacy

- The future of UK-India trade and development – part two

- Trade, human rights and EU-India negotiations

- Can the RCEP strengthen global cooperation for trade, investment and sustainable development?

- Two developments for South-South trade and investments post Covid-19

- A new WTO chief creates opportunity to realise a globally inclusive trading system

- Amid shifting global trade dependencies, can the South provide greater certainty?

- Designing for Impact: South-South Trade and Investment

- Reflections on South-South co-operation on trade and investment ahead of BAPA40

For more on inclusive trade and development, Watch our Inclusive Trade event series.